Lady Greensleeves & Mistress Ford

Anonimo inglese della seconda metà del Cinquecento: Greensleeves. Alfred Deller, controtenore; Desmond Dupré, liuto.

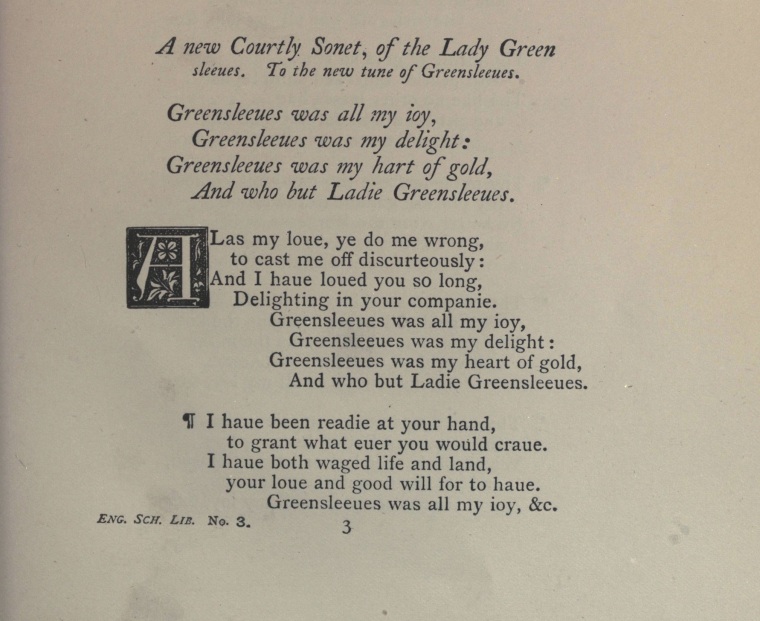

L’interpretazione di Deller e Dupré ci dà modo di ascoltare la più antica versione conosciuta della melodia e, insieme, alcune strofe tratte dalla prima edizione nota del testo, una raccolta del 1584 intitolata A Handful of Pleasant Delites. Ecco il testo completo (le parti in corsivo sono omesse da Deller):

Alas, my love, you do me wrong

To cast me off discourteously,

For I have loved you well and long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you would crave;

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and good-will for to have.

I bought three kerchers to thy head,

That were wrought fine and gallantly;

I kept them both at board and bed,

Which cost my purse well-favour’dly.

I bought thee petticoats of the best,

The cloth so fine as fine might be:

I gave thee jewels for thy chest;

And all this cost I spent on thee.

Thy smock of silk both fair and white,

With gold embroidered gorgeously;

Thy petticoat of sendall right;

And this I bought thee gladly.

Thy girdle of gold so red,

With pearls bedecked sumptously,

The like no other lasses had;

And yet you do not love me!

Thy purse, and eke thy gay gilt knives,

Thy pin-case, gallant to the eye;

No better wore the burgess’ wives;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thy gown was of the grassy green,

The sleeves of satin hanging by;

Which made thee be our harvest queen;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thy garters fringed with the gold,

And silver aglets hanging by;

Which made thee blithe for to behold;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

My gayest gelding thee I gave,

To ride wherever liked thee;

No lady ever was so brave;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

My men were clothed all in green,

And they did ever wait on thee;

All this was gallant to be seen;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

They set thee up, they took thee down,

They served thee with humility;

Thy foot might not once touch the ground;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

For every morning, when thou rose,

I sent thee dainties, orderly,

To cheer thy stomach from all woes;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thou couldst desire no earthly thing,

But still thou hadst it readily,

Thy music still to play and sing;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

And who did pay for all this gear,

That thou didst spend when pleased thee?

Even I that am rejected here,

And thou disdainst to love me!

Well! I will pray to God on high,

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that, yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me!

Greensleeves, now farewell! Adieu!

God I pray to prosper thee!

For I am still thy lover true;

Come once again and love me!

Da una ristampa, datata 1878, di A Handful of Pleasant Delites

Da una ristampa, datata 1878, di A Handful of Pleasant Delites

In una antologia di «musica scespiriana», Greensleeves non può mancare: la canzone della bella signora dalle maniche verdi è infatti menzionata nella commedia The Merry Wives of Windsor (pubblicata per la prima volta nel 1602, ma si ritiene sia stata scritta prima del 1597). La trama è nota: il panciuto e squattrinato cavaliere John Falstaff tenta maldestramente di sedurre due signore, Mistress Ford e Mistress Page, sposate a ricchi borghesi di Windsor (nel Berkshire); ottenendo i loro favori sir John spera di sistemare le proprie finanze, ma viene subito smascherato: le due donne si accorgono di aver ricevuto lettere d’amore identiche, perciò decidono di vendicarsi e ordiscono alcune perfide burle ai danni di Falstaff.

Quando l’imbroglio viene scoperto, questo è il commento di Mistress Ford (atto II, scena 1ª):

I shall think the worse of fat men, as long as I have an eye to make difference of men’s liking: and yet he would not swear; praised women’s modesty; and gave such orderly and well-behaved reproof to all uncomeliness, that I would have sworn his disposition would have gone to the truth of his words; but they do no more adhere and keep place together than the Hundredth Psalm to the tune of Green Sleeves.

È vero, Greensleeves non va d’accordo con il Salmo 100: ma è un impedimento di carattere puramente metrico – i versi («Acclamate il Signore, voi tutti della terra»; nella versione della Great Bible, 1539: «O be joyful in the Lord, all ye lands») non combaciano affatto con la melodia – e non una sorta di divieto morale. L’adattamento di un testo sacro a una melodia profana («travestimento spirituale») non ha mai costituito un problema, e del resto abbiamo già visto (qui) che, nel corso della sua storia pluricentenaria, la stessa Greensleeves ha prestato la propria melodia a un canto religioso.

L’ultima burla ai danni di Falstaff ha luogo nella foresta di Windsor, dove egli viene invitato a recarsi, vestito da cacciatore, per un incontro amoroso (atto V, scena 5ª). «Sir John!», lo apostrofa Mistress Ford, «Art thou there, my deer? my male deer?»; Falstaff risponde affermando che nemmeno una «tempesta di amorose provocazioni», fra le quali la melodia di Greensleeves, riuscirà a distoglierlo da lei:

My doe with the black scut! Let the sky rain potatoes; let it thunder to the tune of Green Sleeves, hail kissing-comfits and snow eringoes; let there come a tempest of provocation, I will shelter me here.

(Qualche breve spiegazione:

– potatoes: quando la patata fu introdotta in Europa, appunto all’epoca di Shakespeare, era considerata afrodisiaca;

– kissing-comfits: dolcetti di zucchero profumati, usati per rinfrescare l’alito;

– eringoes: non si riferisce alle piante erbacee in Italia chiamate calcatreppole, bensì al fungo da noi comunemente noto come cardoncello, nome scientifico pleurotus eryngii, fin dall’Antichità considerato afrodisiaco.)