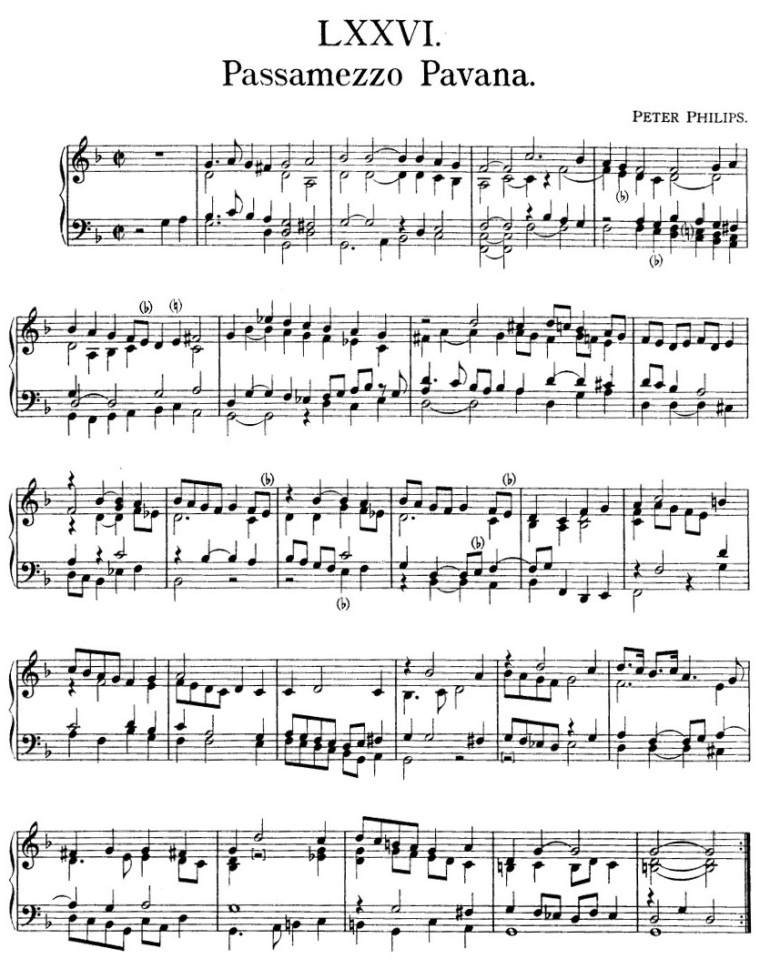

Peter Philips (c1560 - 1628): Passamezzo Pavana e Galiarda Passamezzo (dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, nn. LXXVI-LXXVII). Anneke Uittenbosch, clavicembalo.

Peter Philips (c1560 - 1628): Passamezzo Pavana e Galiarda Passamezzo (dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, nn. LXXVI-LXXVII). Anneke Uittenbosch, clavicembalo.

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, inno su testo di Martin Lutero (ispirato dal Salmo 46) con melodia di Joseph Klug (1529).

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott,

Ein gute Wehr und Waffen.

Er hilft uns frei aus aller Not,

Die uns jetzt hat betroffen.

Der alt böse Feind,

Mit Ernst er’s jetzt meint.

Groß Macht und viel List

Sein grausam Rüstung ist.

Auf Erd ist nicht seinsgleichen.

Mit unsrer Macht ist nichts getan,

Wir sind gar bald verloren.

Es streit’t für uns der rechte Mann,

Den Gott hat selbst erkoren.

Fragst du, wer der ist?

Er heißt Jesus Christ,

Der Herr Zebaoth,

Und ist kein ander Gott.

Das Feld muß er behalten.

Und wenn die Welt voll Teufel wär

Und wollt uns gar verschlingen,

So fürchten wir uns nicht so sehr,

Es soll uns doch gelingen.

Der Fürst dieser Welt,

Wie saur er sich stellt,

Tut er uns doch nicht.

Das macht, er ist gericht’t.

Ein Wörtlein kann ihn fällen.

Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn

Und kein’ Dank dazu haben.

Er ist bei uns wohl auf dem Plan

Mit seinem Geist und Gaben.

Nehmen sie den Leib,

Gut, Ehr, Kind und Weib,

Laß fahren dahin.

Sie haben’s kein Gewinn.

Das Reich muß uns doch bleiben.

Stephan Mahu (c1480/90-1541?): Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Paula Bär-Giese, soprano (interpreta il ruolo di Katharina von Bora, moglie di Lutero); Hein Hof (nei panni di Mahu) l’accompagna al virginale.

Samuel Scheidt (1587-1654): Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Coro Anonymus.

Una squillante versione del celebre corale luterano, eseguita alla tromba da Timothy Moke e all’organo da Georg Masanz.

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, mottetto-corale a 4 voci, con strumenti ad libitum, e basso continuo TVWV 8:7. Magdeburger Kammerchor e Magdeburger Barockorchester, dir. Lothar Hennig.

Il 31 ottobre 1517 Martin Lutero rese pubbliche (secondo la tradizione, affiggendole sul portale della Schlosskirche di Wittenberg) le proprie 95 tesi «sulla dichiarazione del potere delle indulgenze»; per convenzione storica, questo evento è considerato l’inizio della Riforma protestante.

Veduta di Wittenberg, 1536. Sulla sinistra, la Schlosskirche

Veduta di Wittenberg, 1536. Sulla sinistra, la Schlosskirche

Calleno custure me

Anonymous (16th century): Calleno custure me, song. Alfred Deller, countertenor; Desmond Dupré, lute.

When as I view your comely grace

Calleno custure me,

Your golden hairs, your angel’s face,

Calleno custure me.

Your azure veins much like the skies

Your silver teeth, your crystal eyes.

Your coral lips, your crimson cheeks

That gods and men both love and leeks.

My soul with silence moving sense

Doth wish of God with reverence.

Long life and virtue you possess

To match the gifts of worthiness.

The recurring line (chorus) which gives the song its title is probably an adaptation to the English pronunciation of the Irish Cailín ó chois tSiúre mé, i.e. « I am a girl from the Suir-side » (Suir is a river in Ireland that flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Waterford): a harp composition with this title is mentioned in a seventeenth-century Irish poetic text.

The earliest known source for the tune (no text) is William Ballet’s Lute Book, a composite volume containing lute tablature dating back to the late 16th century and owned by the Library of Trinity College, Dublin. Here the piece is performed by Dorothy Linell:

On this tune William Byrd (c1540 - 1623) composed a short but flavorful set of variations for keyboard instrument, preserved in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book under the title Callino Casturame (n. [CLVIII]). YouTube offers various performances: I chose those of David Clark Little on the virginal and Lorenzo Cipriani on the organ.

Calleno custure me often appears in anthologies of Shakespearean music: it is in fact mentioned in Henry V (act 4, scene 4) within a pun that sounds a bit silly today, but which bears witness to the song’s popularity in Shakespeare’s time.

The scene takes place before the battle of Azincourt: Pistol, the king’s old party companion, surprises a French soldier, Le Fer, who has infiltrated the English lines. Fearing that Pistol wants to kill him, the Frenchman tries to cajole him, however speaking to him in his own language:

« Je pense que vous êtes gentilhomme de bonne qualité. »

Unable to understand even a syllable, Pistol replies by mimicking Le Fer’s speech, the sound of whose words evidently reminds him of our song:

« Qualtitie calmie custure me! »

In short, he mimics it with a kind of “meh, meh, meh” but more elegant 🙂

Then Le Fer agrees with Pistol, who frees him for the price of two hundred crowns.

English translation: please click here.

English translation: please click here.

Calleno custure me

Anonimo del XVI secolo: Calleno custure me. Alfred Deller, controtenore; Desmond Dupré, liuto.

When as I view your comely grace

Calleno custure me,

Your golden hairs, your angel’s face,

Calleno custure me.

Your azure veins much like the skies

Your silver teeth, your crystal eyes.

Your coral lips, your crimson cheeks

That gods and men both love and leeks.

My soul with silence moving sense

Doth wish of God with reverence.

Long life and virtue you possess

To match the gifts of worthiness.

Il verso ricorrente che dà titolo alla composizione è probabilmente un adattamento alla pronuncia inglese della frase in gaelico irlandese Cailín ó chois tSiúre mé, ossia « Sono una ragazza delle rive del Suir » (fiume che sfocia nell’Atlantico in prossimità di Waterford): la frase compare quale titolo di una composizione per arpa in un testo poetico irlandese del XVII secolo.

La più antica fonte nota della melodia (priva di testo) è il William Ballet’s Lute Book, una raccolta manoscritta di composizioni intavolate per liuto, risalente al tardo Cinquecento e conservata nella Biblioteca del Trinity College di Dublino. Qui il brano è interpretato da Dorothy Linell:

La melodia è stata rielaborata da William Byrd (c1540 - 4 luglio 1623) in una breve ma saporita serie di variazioni per strumento a tastiera, tramandataci dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book con il titolo Callino Casturame (n. [CLVIII]). YouTube ne offre numerose interpretazioni: ho scelto quelle di David Clark Little al virginale e Lorenzo Cipriani all’organo.

Resta da segnalare che Caleno custure me figura spesso nelle antologie di musiche scespiriane: è infatti citata nell’Enrico V (atto IV, scena 4a) in un gioco di parole che oggi suona alquanto insulso, ma che testimonia la popolarità della canzone all’epoca del Bardo.

La scena si svolge prima della battaglia di Azincourt: Pistol, vecchio compagno di bagordi del re, sorprende un soldato francese, Le Fer, infiltratosi fra le linee inglesi. Temendo che l’altro voglia ammazzarlo, il francese tenta di blandirlo, parlandogli però nella propria lingua:

« Je pense que vous êtes gentilhomme de bonne qualité. »

Non riuscendo a comprendere nemmeno una sillaba, Pistol risponde scimmiottando la parlata di Le Fer, il suono delle cui parole evidentemente gli rammenta il titolo della nostra canzone:

« Qualtitie calmie custure me! »

Gli fa insomma il verso, una specie di “gnegnegné” ma più raffinato 🙂

Le Fer poi si accorda con Pistol, che in cambio di duecento scudi lo lascia libero.

Filippo Azzaiolo (c1530/40 - p1570): Chi passa per ’sta strada, villotta a 4 voci. Eseguita da: The Musicians of Swanne Alley; The King’s Singers; Denis Raisin-Dadre, flauto, e ens. Doulce Mémoire; Yo-Yo Ma, violoncello, e The Silk Road Ensemble; Marco Beasley, voce, e ens. Accordone, dir. Guido Morini.

Chi passa per ‘sta strad’ e non sospira,

Beato s’è,

falalilela,

Beato è chillo chi lo puote fare,

Per la reale.

Affacciati mo’

Se non ch’io moro mo’,

falalilela.

Affacciati, ché tu mi dai la vita,

Meschino me,

falalilela,

Se ‘l cielo non ti possa consolare,

Per la reale.

Affacciati mo’

Se non ch’io moro mo’,

falalilela.

Et io ci passo da sera e mattina,

Meschino me,

falalilela,

Et tu, crudele, non t’affacci mai,

Perché lo fai?

Affacciati mo’

Se non ch’io moro mo’,

falalilela.

Compar Vassillo, che sta a loco suo,

Beato s’è,

falalilela,

Salutami ‘no poco la comare,

Per la reale.

Affacciati mo’

Se non ch’io moro mo’,

falalilela.

Giacomo Gorzanis (1525 - 1578): Padoana detta Chi passa per questa strada (trascrizione della villotta di Azzaiolo). Massimo Lonardi, liuto.

Anonimo (Inghilterra, sec. XVI): Chi passa (dal Marsh lute book). Valéry Sauvage, liuto.

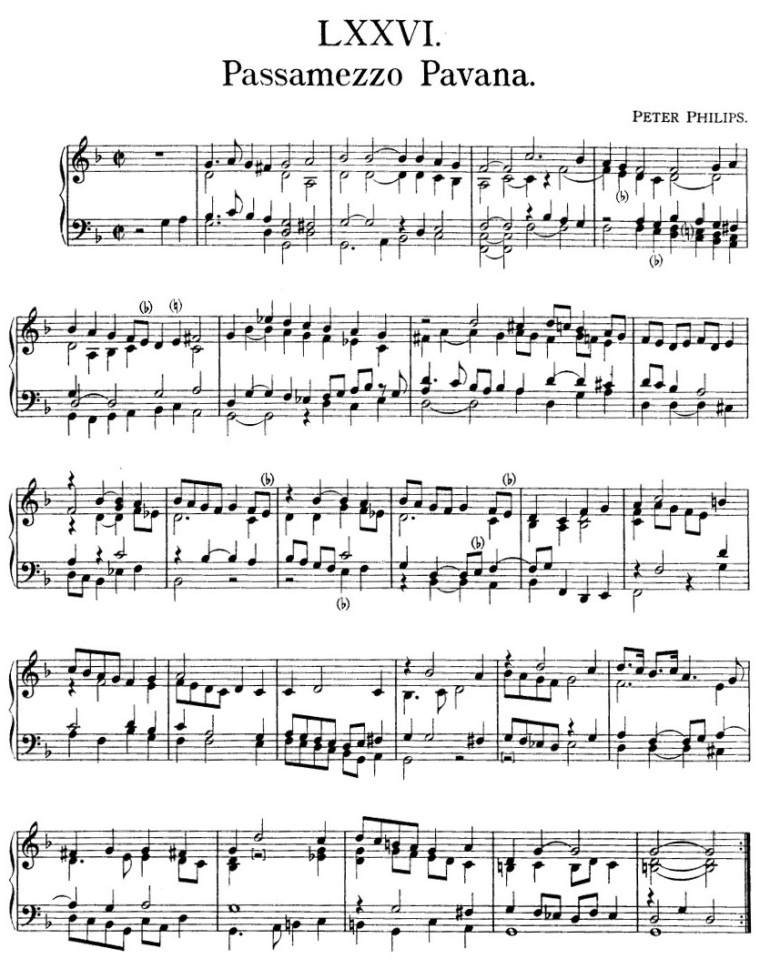

William Byrd (c1540 - 1623): Qui Passe, dal My Ladye Nevells Booke (n. 2). Timothy Roberts, virginale.

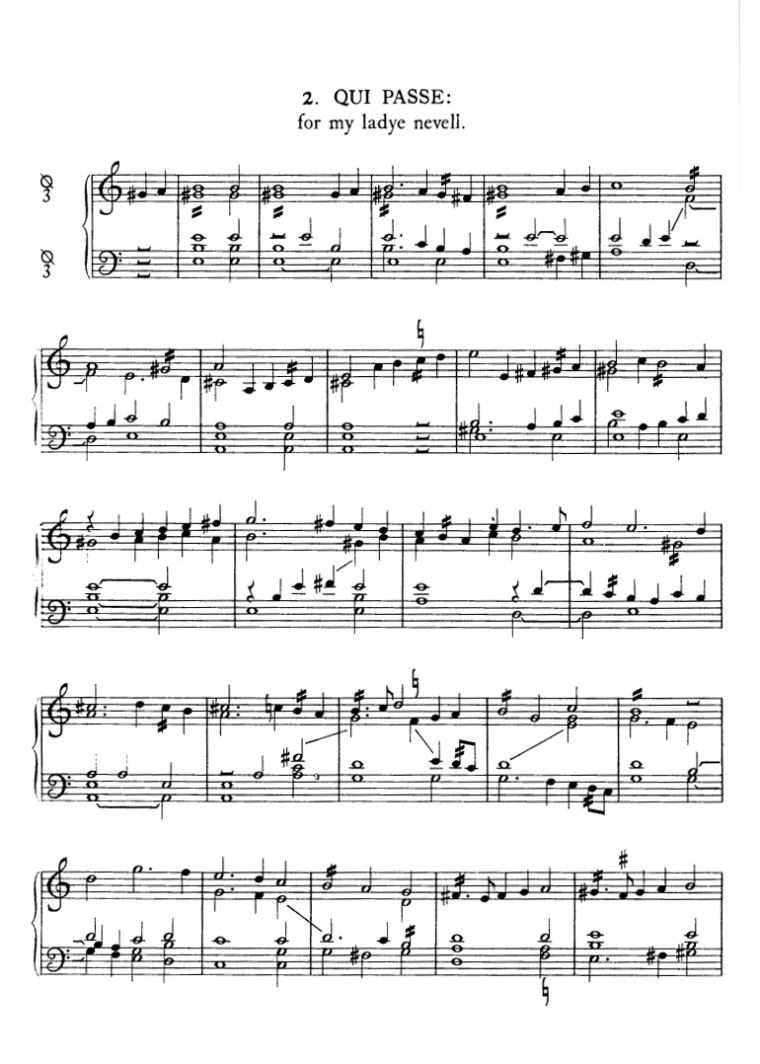

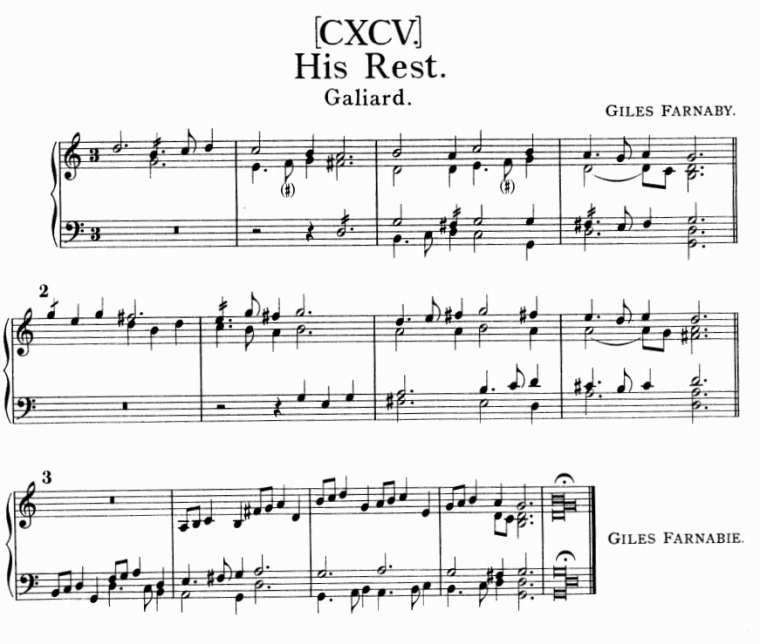

Giles Farnaby (1563 - 25 novembre 1640): Giles Farnaby’s Dreame e His Rest – Galiard (dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, n. [CXCIV] e [CXCV]). Ernst Stolz, virginale.

John Munday (o Mundy; 1550 o 1554 - 29 giugno 1630): Munday’s Joy (dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, n. [CCLXXXII]). Timur Khaliullin, clavicembalo.