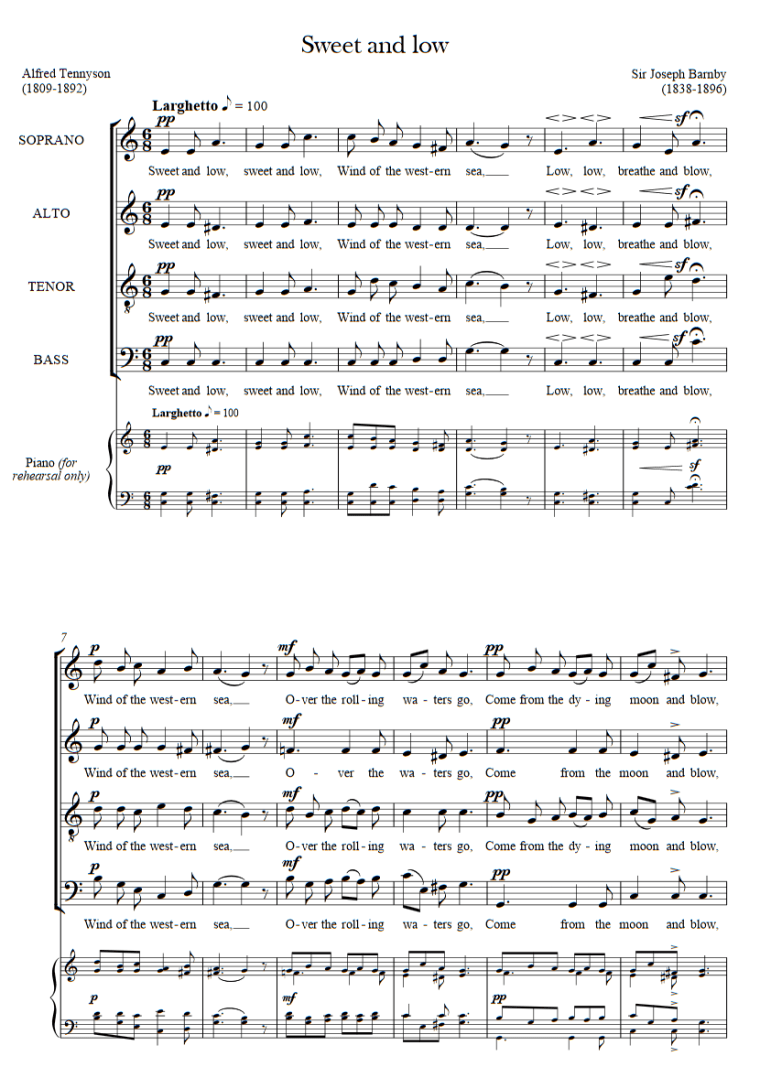

Joseph Barnby (1838 - 28 gennaio 1896): Sweet and low (1863), testo di Alfred Tennyson (da The Princess). New York Polyphony: Geoffrey Williams, controtenore; Steven Caldicott Wilson, tenore; Christopher Dylan Herbert, baritono; Craig Phillips, basso.

(«Geoff would like to apologize for wearing shorts to a video shoot».)

Sweet and low, sweet and low

Wind of the western sea,

Low, low, breathe and blow,

Wind of the western sea!

Over the rolling waters go,

Come from the dying moon, and blow,

Blow him again to me,

While my little one, while my pretty one, sleeps.

Sleep and rest, sleep and rest,

Father will come to thee soon;

Rest, rest, on mother’s breast,

Father will come to thee soon;

Father will come to his babe in the nest,

Silver sails all out of the west

Under the silver moon!

Sleep my little one, sleep my pretty one, sleep.

L’approfondimento

di Pierfrancesco Di Vanni

Note sacre e rigore vittoriano: la vita straordinaria di Sir Joseph Barnby

Le origini e la formazione: un talento precoce

Nato a York nel 1838, Joseph Barnby respirò musica fin dalla nascita, essendo figlio d’arte (suo padre Thomas era un organista). Il suo percorso iniziò come corista presso la Cattedrale di York all’età di sette anni, una palestra fondamentale per la sua futura carriera. Dopo il cambiamento della voce a quindici anni, proseguì gli studi d’eccellenza alla Royal Academy of Music di Londra, sotto la guida di Cipriani Potter e Charles Lucas. Un aneddoto significativo del suo periodo studentesco riguarda la competizione per la prestigiosa borsa di studio «Mendelssohn», in cui fu sconfitto per un soffio da quello che sarebbe diventato un altro gigante della musica britannica: Arthur Sullivan.

L’ascesa professionale e la rottura dei pregiudizi

La carriera di Barnby come organista fu segnata da una costante ricerca dell’eccellenza liturgica. Nel 1862, presso la Chiesa di St Andrew a Londra, portò i servizi musicali a livelli qualitativi altissimi. Fu proprio qui che, nel 1864, Barnby compì un gesto rivoluzionario per l’epoca: diresse due inni composti da Alice Mary Smith. Si trattò, con ogni probabilità, della prima volta in assoluto che la musica liturgica composta da una donna veniva eseguita ufficialmente all’interno della Chiesa d’Inghilterra.

La direzione corale e il prestigio accademico

Barnby consolidò la propria fama soprattutto come direttore. Fondò il Barnby’s Choir e nel 1871 succedette a Charles Gounod alla guida della Royal Albert Hall Choral Society, ruolo che mantenne con dedizione fino alla morte. La sua influenza si estese anche all’ambito educativo: fu direttore musicale all’Eton College per diciassette anni e, nel 1892, divenne preside della Guildhall School of Music. Questi meriti professionali, uniti al suo contributo culturale, gli valsero il titolo di cavaliere nel luglio del 1892.

Innovazione e repertorio: da Bach a Wagner

Oltre che un prolifico compositore di inni (ne pubblicò ben 246), oratori e canti popolari (come la celebre ninna_nanna Sweet and Low), Barnby fu un instancabile promotore della grande musica europea. Fu un fervente sostenitore di J.S. Bach, proponendo un’esecuzione storica della Passione secondo Giovanni nel 1870 con un coro imponente di 500 voci. Ebbe inoltre il merito di far conoscere la musica sacra di Gounod al grande pubblico londinese e di organizzare una memorabile esecuzione concertistica del Parsifal di Wagner alla Royal Albert Hall nel 1884, nonostante non nutrisse una particolare simpatia per il genere operistico.

Visione critica e un’arguzia leggendaria

Barnby possedeva un’opinione netta sui suoi contemporanei: lodava la chiarezza di Sullivan, ma guardava con scetticismo i compositori morsi dal desiderio di produrre musica troppo “avanzata” o sperimentale. La sua immagine pubblica era quella di un uomo rigoroso ma dotato di un’ironia tagliente: un celebre aneddoto racconta di una giovane contralto che, durante un assolo di Handel, decise di variare la partitura aggiungendo una nota alta per mettere in mostra le proprie doti vocali. Quando la cantante si giustificò dicendo: «Sir Joseph, ho un mi alto e non vedo perché non mostrarlo», Barnby rispose prontamente: «Signorina, credo che lei abbia anche due ginocchia, ma spero vivamente che non voglia metterle in mostra qui». Il compositore si spense nel 1896 e, dopo un solenne funerale nella Cattedrale di St Paul, fu sepolto a West Norwood, lasciando un’impronta indelebile nella tradizione corale inglese.

Sweet and Low

Si tratta di un esempio magistrale di part-song vittoriano, dove la musica si fonde indissolubilmente con i versi di Alfred Tennyson per creare una ninna-nanna di rara delicatezza. Sebbene il brano sia stato originariamente concepito per coro misto (SATB), questa versione per quartetto vocale maschile conferisce al brano una sonorità densa, calda e vellutata.

Il brano segue una struttura strofica, rispettando le due stanze del poema di Tennyson. Il metro utilizzato è un 6/8, la scelta ritmica per eccellenza per una ninna-nanna, poiché evoca naturalmente il movimento oscillatorio di una culla o il moto calmo delle onde del mare citate nel testo.

La melodia è caratterizzata da una semplicità apparente, ma ricca di sfumature armoniche. Le parole «Sweet and low» sono intonate su una cellula melodica discendente che trasmette immediatamente un senso di rilassamento e abbandono. L’omofonia è quasi totale, trasformando il quartetto in un unico strumento armonico.

Nella sezione centrale di ogni strofa, Barnby introduce lievi tensioni cromatiche e modulazioni passeggere: queste “increspature” armoniche descrivono visivamente il movimento dell’acqua e la luce argentea della luna, senza però mai rompere la pace della composizione.

La gestione delle dinamiche è fondamentale: i cantori passano da un mezzoforte caldo a un pianissimo quasi sussurrato. Particolarmente suggestivo è il finale di ogni strofa, dove le voci si spengono gradualmente in una cadenza perfetta che simboleggia lo scivolare nel sonno profondo.

Barnby è un maestro nel sottolineare i fonemi del testo di Tennyson: si noti come la parola «low» venga spesso eseguita con una nota lunga e profonda che sembra ancorare la melodia al suolo, mentre nel passaggio «While my little one, while my pretty one, sleeps», la scrittura diventa leggermente più mossa, quasi a imitare il battito calmo di un cuore, per poi risolversi nella stasi finale.

Nel complesso, il pezzo emerge come un gioiello di equilibrio formale. La capacità del compositore di tradurre il sentimentalismo vittoriano in una forma nobile e mai banale trova nel quartetto maschile degli interpreti ideali, capaci di trasformare una semplice ninna nanna in una meditazione profonda sulla nostalgia, la famiglia e la pace domestica.