Kenneth Hesketh (20 luglio 1968): Danceries per banda sinfonica, 1ª serie (1999). The Symphonic Band of the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music at California State University, Long Beach,, dir. Ricardo J. Espinosa.

- Lull me beyond thee: Andante espressivo

- Catching of Quails: Vivace vigoroso [3:21]

- My Lady’s Rest: Andantino con sentimento [5:50]

- Quodling’s Delight: Allegro vivace – Con fuoco [11:05]

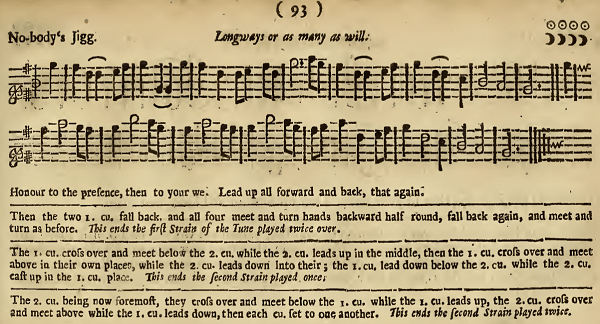

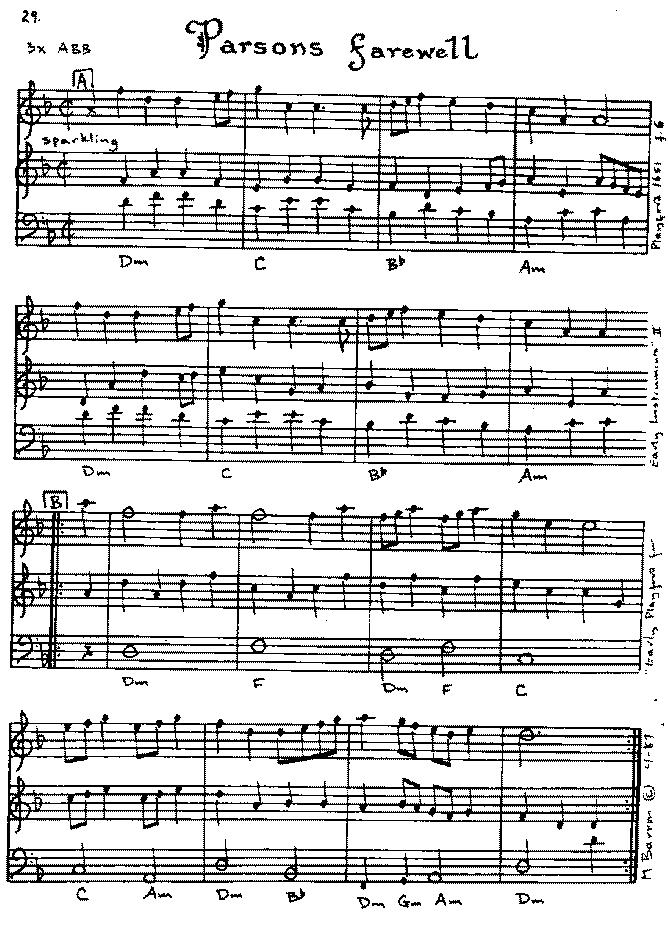

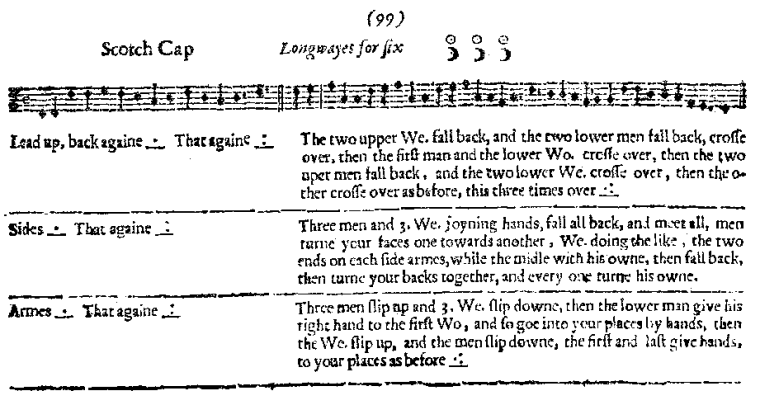

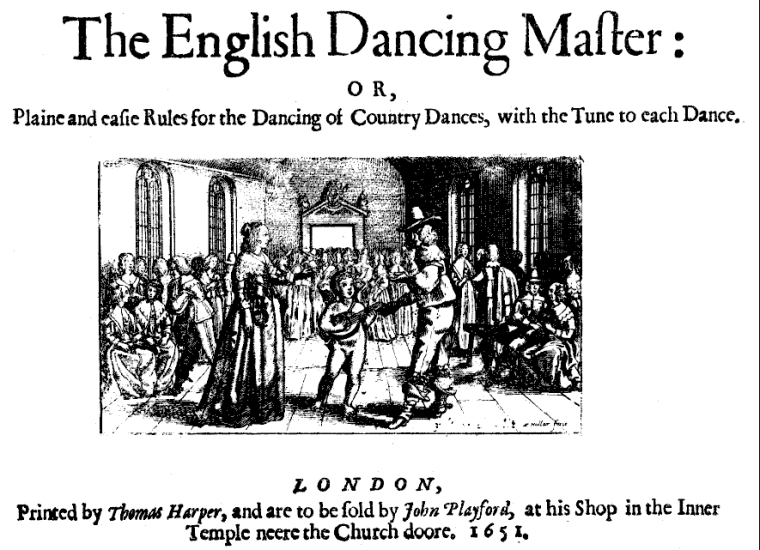

Se la suite prende il titolo da famose raccolte rinascimentali di musiche per danza, e in particolare dal celebre Het derde musyck boexken… alderhande danserye (Il terzo libriccino di musica… ovvero danserye) pubblicato nel 1551 ad Anversa da Tielman Susato, e più volte ospitato in questo blog, alcuni dei brani che la compongono sono libere rielaborazioni di brani che fanno parte del repertorio tradizionale britannico, e in special modo della famosa antologia curata da John Playford ed eredi e pubblicata, con il titolo The English Dancing Master, per la prima volta giusto cent’anni dopo la silloge di Susato. Mentre Catching of Quails e My Lady’s Rest sono a tutti gli effetti creazioni originali di Hesketh, il primo e l’ultimo movimento riprendono i brani intitolati rispettivamente Poor Robin’s Maggot e Goddesses nella silloge di Playford. Di quest’ultimo componimento ci eravamo già occupati tempo fa nella nostra personale crestomazia di folk songs (vedere qui).

L’approfondimento

di Pierfrancesco Di Vanni

Kenneth Hesketh, architetto di mondi sonori tra entropia e incanto

Hesketh è un compositore britannico di spicco nel panorama della musica classica contemporanea. La sua produzione è vasta e diversificata, spaziando da opere orchestrali e da camera a composizioni vocali, per strumenti solisti, per banda di fiati, fino alla musica corale.

Formazione e primi passi: un talento precoce

Nato a Liverpool, Hesketh mostrò fin da giovanissimo una considerevole predisposizione per la musica. Completò un primo lavoro sinfonico all’età di soli tredici anni, quando era fanciullo cantore presso la Cattedrale anglicana di Liverpool. Il suo talento non passò inosservato: a diciannove anni ricevette una prima commissione ufficiale dalla Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, diretta da sir Charles Groves.

La formazione accademica di Hesketh è di altissimo livello: ha studiato al Royal College of Music di Londra con Edwin Roxburgh e Simon Bainbridge fra gli altri. Un’esperienza formativa cruciale è stata la partecipazione al Festival di Tanglewood nel 1995 come “Leonard Bernstein Fellow”: in tale occasione ha avuto l’opportunità di studiare con il compositore francese Henri Dutilleux. Dopo un corso di perfezionamento all’Università del Michigan, la sua carriera è stata costellata di premi e riconoscimenti, tra cui una borsa di studio dalla Fondazione Toepfer su indicazione di sir Simon Rattle, che si rivelerà una figura chiave nel suo percorso.

L’evoluzione dello stile musicale

Lo stile di Hesketh è riconoscibile per la sua strumentazione ricca e colorata, le armonie dense e un linguaggio ritmico estremamente dinamico e mobile. L’evoluzione artistica di questo musicista può essere suddivisa in due fasi tematiche.

Prima fase: simbolismo e letteratura fantastica. Le prime opere di Hesketh sono spesso ispirate da idee extra-musicali, in particolare dal simbolismo e dall’iconografia medievale. Brani come Theatrum (1996) e Torturous Instruments (1997-98) – quest’ultimo ispirato all’Inferno musicale di Hieronymus Bosch – ne sono un esempio. Il punto di svolta è arrivato con The Circling Canopy of Night (1999), commissionato per il Birmingham Contemporary Music Group e diretto per la prima volta da Sir Simon Rattle. L’opera, descritta come “un vortice scintillante di colori notturni”, è stata poi sostenuta da un altro gigante della musica contemporanea, Oliver Knussen, e ha ricevuto esecuzioni ai BBC Proms e al Concertgebouw di Amsterdam. In questo periodo, Hesketh ha anche esplorato la natura sinistra e malinconica della letteratura per l’infanzia, come in Netsuke (2000-1), ispirato a Il Piccolo Principe e allo Struwwelpeter, e in Small Tales, tall tales (2009), basato sulle fiabe dei Fratelli Grimm.

Fase della maturità: macchine inaffidabili, entropia e labirinti. L’interesse del compositore si sposta verso quelle che egli stesso definisce “macchine inaffidabili”: brevi frammenti di materiale musicale meccanicistico che si ripetono, si trasformano e infine si esauriscono. Questo concetto si è ampliato per includere temi filosofici come l’entropia (in termini umanistici), l’invecchiamento, la morte e il fallimento dei sistemi fisici. Opere come Knotted Tongues (2012) e In Ictu Oculi (cui è stato conferito il British Composer Award nel 2017) riflettono questa fascinazione. Parallelamente, Hesketh inizia a integrare aspetti della composizione assistita dal computer e procedure randomizzate limitate, che hanno reso il suo approccio più libero e astratto. Questo interesse per la mutazione e l’esistenzialismo coesiste con una notevole attenzione per il disegno formale, ispirato a “percorsi” come labirinti e dedali, e alla nozione paradossale di raggiungere la chiarezza attraverso la densità.

Una carriera coronata dal successo

La carriera di Hesketh è un susseguirsi di commissioni prestigiose, premi e collaborazioni di alto profilo. È stato Composer in the House presso la Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, un ruolo che è culminato nella prima esecuzione di Graven Image ai BBC Proms del 2008. La composizione Forms entangled, shapes collided, nata come parte di una collaborazione fra l’ensemble di musica contemnporanea Psappha e la coreografa Sharon Watson, direttore artistico del Phoenix Dance Theatre di Leeds è infine approdata alla Royal Opera House.

All’attività di compositore, Hesketh affianca quella didattica e accademica: professore di composizione presso il Royal College of Music, è inoltre professore onorario all’Università di Liverpool. Vive a Londra con la moglie, la compositrice statunitense Arlene Sierra, e il loro figlio.

Danceries, 1ª serie: analisi

Composta nel 1999, la prima serie di Danceries di Hesketh rappresenta lo stile del compositore nella sua fase giovanile. Il titolo stesso evoca le suite di danze rinascimentali e barocche, ma il compositore non si limita a una semplice imitazione: al contrario, utilizza queste forme storiche come trampolino di lancio per esplorare il suo personalissimo linguaggio musicale, caratterizzato da una strumentazione vivida e colorata, armonie dense e un’energia ritmica inarrestabile.

Il primo movimento si presenta come una ninna-nanna trasfigurata, un brano di una bellezza lirica e introspettiva. L’inizio è affidato a un delicato intreccio di legni: clarinetti e flauti espongono una melodia dolce e sinuosa, sostenuta da armonie calde ma velate di malinconia. La scrittura è trasparente e cameristica, permettendo di apprezzare ogni singola sfumatura timbrica. L’uso discreto delle percussioni aggiunge tocchi di luce scintillante, creando un’atmosfera notturna e sognante, che rimanda a opere coeve come The Circling Canopy of Night. La struttura del movimento segue un arco dinamico ed emotivo: dalla quiete iniziale, la musica si sviluppa gradualmente, coinvolgendo progressivamente l’intera compagine. La melodia viene poi ripresa con maggiore intensità dagli ottoni, costruendo una sonorità piena e sontuosa, tipica della densità armonica di Hesketh. Questo climax emotivo, tuttavia, non è mai aggressivo e mantiene sempre un carattere espressivo e cantabile prima di dissolversi lentamente, tornando alla serenità dell’apertura. Il finale è un sussurro, un suono che si spegne dolcemente, lasciando l’ascoltatore sospeso in un’atmosfera di pace contemplativa.

Con un contrasto netto, il secondo movimento irrompe con un’energia giocosa e scattante. “A caccia di quaglie”, i legni si lanciano in rapidi fraseggi staccati e agili che imitano il cinguettio e il volo frenetico degli uccelli. Questo è un chiaro esempio della scrittura ritmicamente “mobile” e complessa di Hesketh. Il brano è un brillante scherzo, un mosaico di brevi frammenti ritmici e melodici che vengono scambiati tra le varie sezioni dell’ensemble in un dialogo serrato e spiritoso. Le percussioni assumono un ruolo di primo piano, sottolineando il carattere vivace e quasi meccanicistico della musica, un’anticipazione di quell’interesse per le “macchine inaffidabili” che caratterizzerà le sue opere successive. Nonostante la sua brevità, il movimento è denso di idee e mette in mostra la straordinaria abilità di Hesketh nel creare trame complesse e piene di vita, per poi concludersi con un gesto tanto improvviso quanto efficace.

Il terzo movimento è il cuore emotivo della suite: il titolo nobiliare e il carattere “con sentimento” ci trasportano in un’atmosfera completamente diversa: solenne, riflessiva e profondamente lirica. L’inizio è un maestoso corale affidato ai registri gravi, con gli ottoni e i legni bassi che creano un tappeto armonico ricco e profondo. Da questo sfondo emergono diverse voci soliste: un lungo e struggente assolo del flauto si libra con grazia sopra l’accompagnamento, seguito da interventi espressivi dell’oboe, del clarinetto e di altri legni. Hesketh dimostra qui la sua maestria nella strumentazione “colorata”, mettendo in risalto la bellezza timbrica di ogni strumento. La musica costruisce lentamente una tensione emotiva che culmina in un climax grandioso e appassionato, dove l’intera forza della banda sinfonica viene scatenata in un’ondata sonora potente e catartica. Come nel primo movimento, la tensione si allenta progressivamente, e il brano si conclude in una lunga coda serena, una discesa verso una pace quasi ultraterrena che evoca perfettamente l’idea del “riposo”.

Il finale è una danza sfrenata, un’esplosione di gioia ed energia rustica e popolare, e la musica è un turbine di vitalità “con fuoco”. L’inizio è percussivo e travolgente, con ritmi ostinati e figure di fanfara che si rincorrono tra le sezioni. Questo movimento è un tour de force ritmico e strumentale: i tempi veloci, le sincopi accentuate e i continui cambi di metro creano una sensazione di instabilità controllata, come una danza popolare sull’orlo del caos. Tutto l’insieme strumentale è impegnato al massimo: i legni eseguono passaggi virtuosistici, gli ottoni intonano temi trionfali e le percussioni forniscono una spinta ritmica inesorabile. Il brano è un susseguirsi di idee che vengono continuamente trasformate e sviluppate, mantenendo alta la tensione fino alla coda finale, dove Hesketh scatena tutta la potenza dell’ensemble in una conclusione brillante, affermativa e spettacolare, chiudendo la suite con un’impronta di esuberanza indimenticabile.