Many sighs about nothing

Thomas Augustine Arne (1710 - 1778): Sigh no more, ladies, dalle musiche di scena (1748) per Much ado about nothing di W. Shakespeare (atto II, scena 3a).

– Versione per voce solista e orchestra d’archi: Alexander Young, tenore; Martin Isepp, clavicembalo; Wiener Rundfunkorchester, dir. Brian Priestman.

– Versione per 3 voci virili (TTB) a cappella: The Hilliard Ensemble.

Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more.

Men were deceivers ever,

One foot in sea, and one on shore,

To one thing constant never.

Then sigh not so, but let them go,

And be you blithe and merry,

Converting all your sounds of woe

Into hey down derry.

Sing no more ditties, sing no more

Of dumps so dull and heavy.

The fraud of men was ever so

Since summer first was leavy.

Then sigh not so, but let them go,

And be you blithe and merry,

Converting all your sounds of woe

Into hey down derry.

Guillaume Lekeu (1870 - 1894): Étude symphonique no. 2: Hamlet et Ophélie (1889). Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège, dir. Pierre Bartholomée.

Guillaume Lekeu (1870 - 1894): Étude symphonique no. 2: Hamlet et Ophélie (1889). Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège, dir. Pierre Bartholomée.  Josef Bohuslav Foerster (1859 - 1951): Suita ze Shakespeareho per orchestra op. 76 (1908-09). Orchestra sinfonica di Praga, dir. Václav Smetáček.

Josef Bohuslav Foerster (1859 - 1951): Suita ze Shakespeareho per orchestra op. 76 (1908-09). Orchestra sinfonica di Praga, dir. Václav Smetáček.

Friedrich Kuhlau (1786 - 1832): Ouverture dalle musiche di scena op. 74 per il dramma William Shakespeare di Caspar Johannes Boye (1826). Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester, dir. Vladimir Ziva.

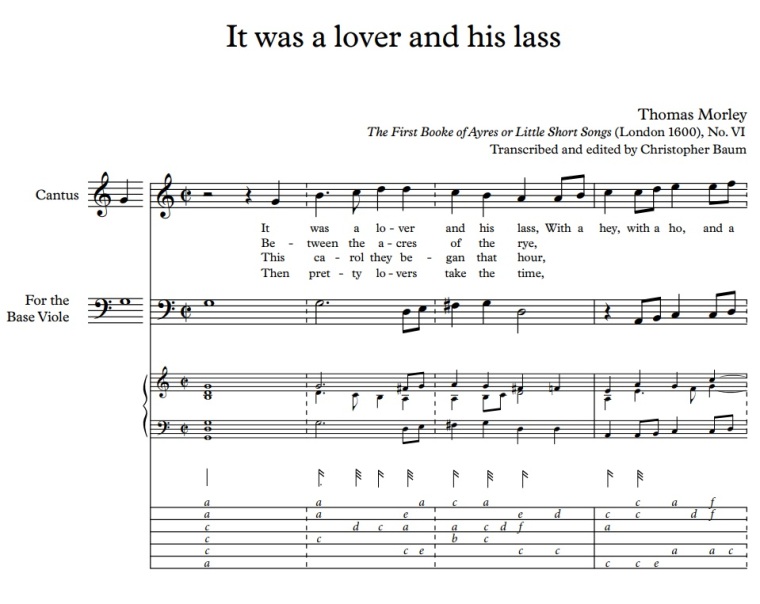

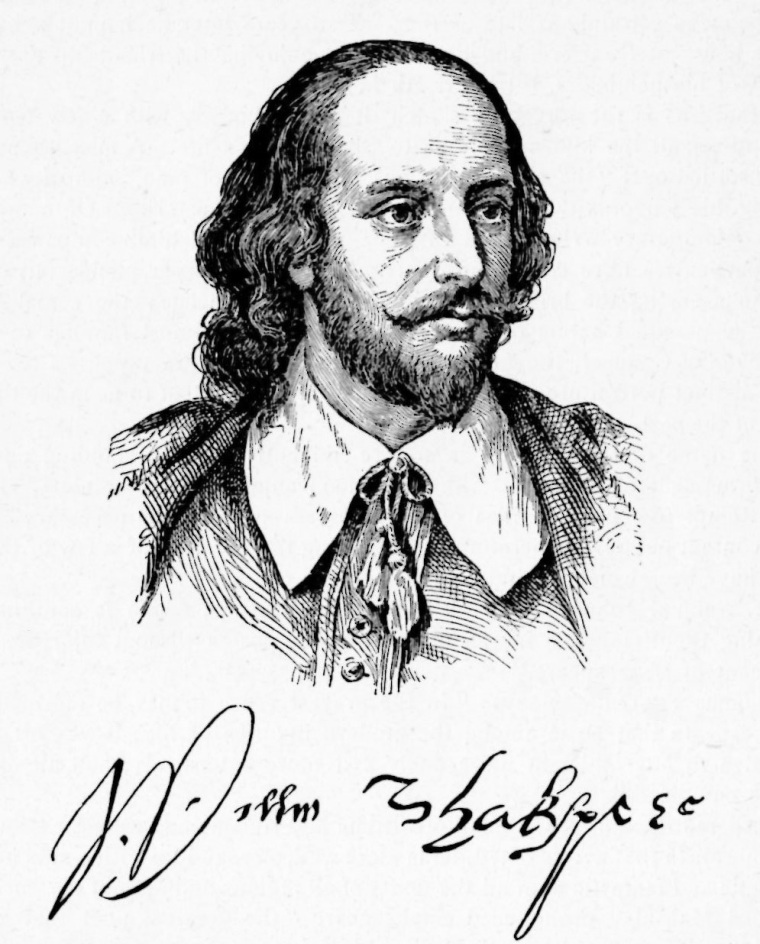

Friedrich Kuhlau (1786 - 1832): Ouverture dalle musiche di scena op. 74 per il dramma William Shakespeare di Caspar Johannes Boye (1826). Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester, dir. Vladimir Ziva.  Thomas Morley è uno dei più importanti compositori di musica profana dell’Inghilterra elisabettiana; insieme con Robert Johnson (c1583-c1634) è autore delle uniche composizioni coeve su versi di Shakespeare che ci siano pervenute. Morley è ricordato, oltre che per le sue composizioni, per aver pubblicato un trattato musicale (A Plain and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, 1597) che ebbe vasta popolarità per oltre duecento anni e che tuttora è considerato fondamentale perché contiene preziose informazioni sulla musica dell’epoca.

Thomas Morley è uno dei più importanti compositori di musica profana dell’Inghilterra elisabettiana; insieme con Robert Johnson (c1583-c1634) è autore delle uniche composizioni coeve su versi di Shakespeare che ci siano pervenute. Morley è ricordato, oltre che per le sue composizioni, per aver pubblicato un trattato musicale (A Plain and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, 1597) che ebbe vasta popolarità per oltre duecento anni e che tuttora è considerato fondamentale perché contiene preziose informazioni sulla musica dell’epoca.  Thomas Morley is one of the most important composers of secular music in Elizabethan England; he and Robert Johnson (c1583-c1634) are the authors of the only surviving contemporary musical settings on lyrics by Shakespeare. Morley is remembered, as well as for his compositions, for a musical treatise (A Plain and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, 1597) which had large popularity for almost two centuries and even today is an important reference for information about sixteenth century music.

Thomas Morley is one of the most important composers of secular music in Elizabethan England; he and Robert Johnson (c1583-c1634) are the authors of the only surviving contemporary musical settings on lyrics by Shakespeare. Morley is remembered, as well as for his compositions, for a musical treatise (A Plain and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, 1597) which had large popularity for almost two centuries and even today is an important reference for information about sixteenth century music.