Franz Doppler (1821 - 27 luglio 1883): Concerto in re minore per 2 flauti e orchestra (). Patrick Gallois e Kazunori Seo, flauti; Jyväskylä Sinfonia, dir. Patrick Gallois.

- Allegro maestoso

- Andante [8:06]

- Allegro [11:32]

Franz Doppler (1821 - 27 luglio 1883): Concerto in re minore per 2 flauti e orchestra (). Patrick Gallois e Kazunori Seo, flauti; Jyväskylä Sinfonia, dir. Patrick Gallois.

Con il suo ensemble, The Broadside Band, Jeremy Barlow ha lavorato a lungo e proficuamente sulle musiche utilizzate da Johann Christoph Pepusch nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728) di John Gay: la quale è l’unica ballad opera di cui si parli ancora ai nostri giorni, grazie anche al rifacimento brechtiano del 1928, Die Dreigroschenoper, che adotta però musiche originali composte da Kurt Weill. Per l’Opera del mendicante invece, com’è noto, Pepusch adattò i testi di Gay a melodie che all’epoca avevano una certa notorietà, prendendole a prestito da broadside ballads, arie d’opera, inni religiosi e canti di tradizione popolare.

Oltre a produrre un’edizione completa del lavoro di Gay e Pepusch, Barlow e la sua band hanno inciso (per Harmonia Mundi, 1982) anche un’antologia degli airs più famosi (in tutto nove brani), di ciascuno dei quali proponendo non solo la versione dell’Opera del mendicante ma anche la composizione originale e eventuali altre sue trasformazioni, varianti e parodie.

L’ultima sezione dell’antologia, che qui sottopongo alla vostra attenzione, è dedicato a Greensleeves. Comprende, nell’ordine:

una improvvisazione sul passamezzo antico, eseguita al liuto da George Weigand

Greensleeves, la più antica versione nota della melodia (dal William Ballet’s Lute Book, c1590-1603) con la più antica versione nota del testo (da A Handful of Pleasant Delights, 1584), cantata da Paul Elliott accompagnato al liuto da Weigand [1:13]

Alas, my love, you do me wrong,

To cast me off discourteously.

And I have loved you so long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my Lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you wouldst crave,

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and goodwill for to have.

Well I will pray to God on high

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me.

Greensleeves, now farewell, adieu,

God I pray to prosper thee,

For I am still thy lover true,

Come once again and love me.

Greensleeves, la versione più diffusa all’inizio del Seicento, secondo William Cobbold (1560 - 1639) e altri autori, con improvvisazioni eseguite da Weigand alla chitarra barocca e da Rosemary Thorndycraft al bass viol [4:07]

la versione dell’Opera del mendicante che già conosciamo, interpretata ancora da Elliott a solo [5:27]

un misto di tre jigs irlandesi eseguito da Barlow al flauto e da Alastair McLachlan al violino [6:03]:

– A Basket of Oysters (da Moore’s Irish Melodies, 1834)

– A Basket of Oysters or Paddythe Weaver (Aird’s selection, 1788)

– Greensleeves (versione raccolta a Limerick nel 1852)

With his ensemble, The Broadside Band, Jeremy Barlow worked extensively and profitably on the music used by Johann Christoph Pepusch in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728): it is the only ballad opera still being talked about in our days, thanks also to Bertolt Brecht’s 1928 remake, Die Dreigroschenoper, which however has original music composed by Kurt Weill. It is not the same for The Beggar’s Opera: Gay’s lyrics were in fact adapted by Pepusch to melodies that at the time already had a certain notoriety, borrowing them from broadside ballads, opera arias, religious hymns and folk songs.

Barlow and his band have recorded a complete edition of Gay and Pepusch’s work, as well as an anthology of its most famous airs (nine pieces in all), of each of which they presented not only The Beggar’s Opera version, but also the original composition and some of its variants and parodies.

The last track of the anthology, the one I submit to your attention here, is dedicated to Greensleeves. It includes, in order:

a lute extemporisation on passamezzo antico ground, performed by George Weigand

Greensleeves, earliest version of melody (from William Ballet’s Lute Book, c1590-1603) with earliest surviving words (A Handful of Pleasant Delights, 1584), sung by Paul Elliott accompanied on lute by Weigand [1:13]

Alas, my love, you do me wrong,

To cast me off discourteously.

And I have loved you so long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my Lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you wouldst crave,

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and goodwill for to have.

Well I will pray to God on high

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me.

Greensleeves, now farewell, adieu,

God I pray to prosper thee,

For I am still thy lover true,

Come once again and love me.

Greensleeves, the most widespread version at the beginning of the seventeenth century, according to William Cobbold (1560 - 1639) and other authors, with improvisations performed by Weigand on baroque guitar and by Rosemary Thorndycraft on bass viol [4:07]

The Beggar’s Opera version (we already know it) sung by Elliott a solo [5:27]

a medley of three Irish jigs performed by Barlow on flute and Alastair McLachlan on violin [6:03]:

– A Basket of Oysters (da Moore’s Irish Melodies, 1834)

– A Basket of Oysters or Paddythe Weaver (Aird’s selection, 1788)

– Greensleeves (collected Limerick 1852).

Eduard Schütt (1856 - 26 luglio 1933): Scènes champêtres, quatre morceaux caractéristiques pour piano à 4 mains op. 46 (1895). Andrea Bambace e Sabrina Kang.

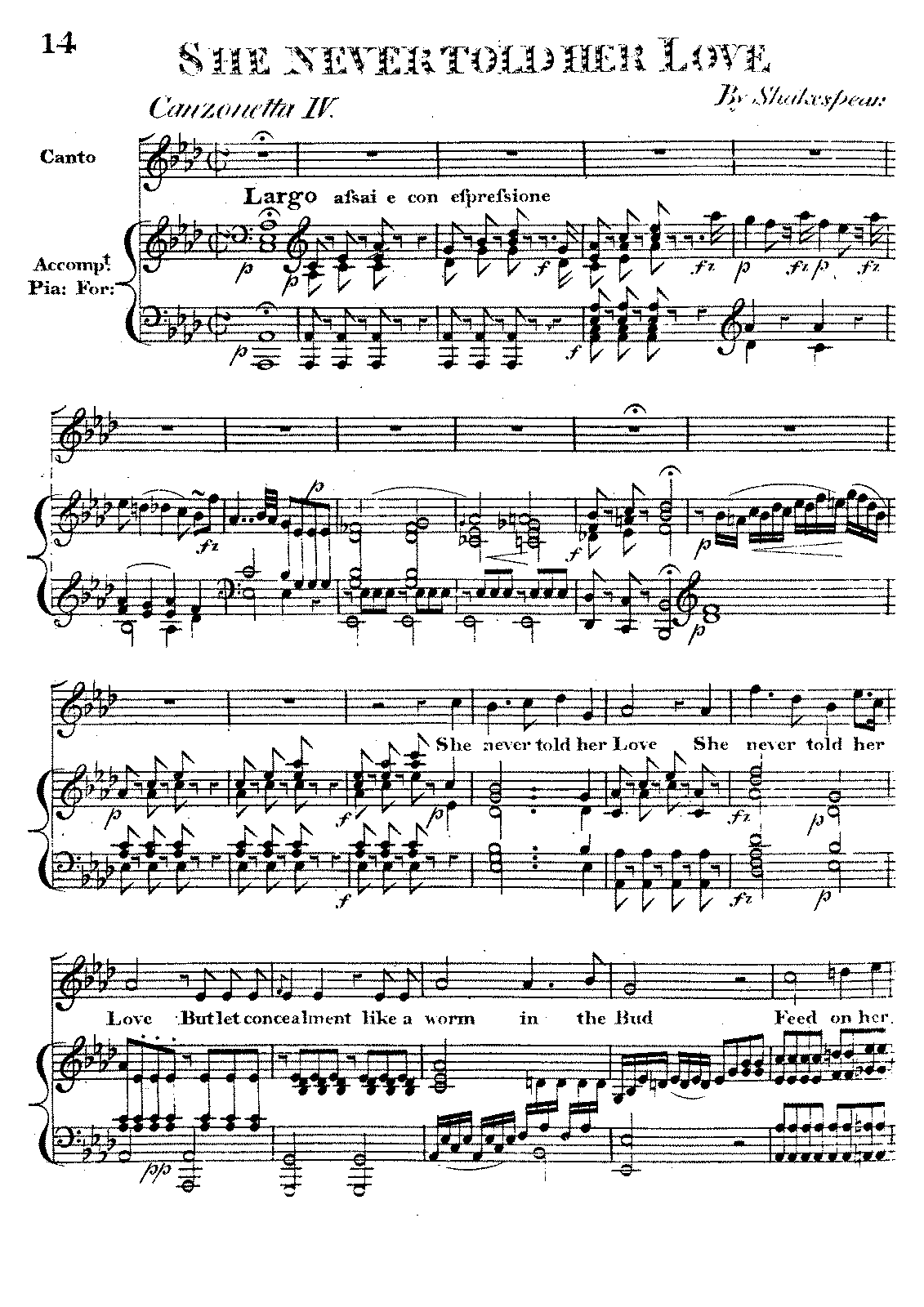

Like a worm in the bud

Franz Josef Haydn (1732 - 1809): She never told her love, canzonetta for voice and keyboard instrument Hob.XXVIa:34 (1794-95); lyrics by William Shakespeare (Twelfth Night, act 2, scene 4). Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Melvyn Tan, fortepiano.

She never told her love,

but let concealment,

like a worm in the bud,

feed on her damask cheek,

she sat,

like patience on a monument,

smiling, smiling at grief.

Alfredo Casella (25 luglio 1883 - 1947): Sinfonia n. 3 op. 63 (1939-40). Orchestra sinfonica di Roma, dir. Francesco La Vecchia.

Agostino Steffani (25 luglio 1654 - 1728): Stabat mater a 6 voci, coro, archi e basso continuo (1728). Coro della Radio Svizzera, dir. Diego Fasolis; I Barocchisti, dir. René Clemencic.

Agostino Steffani (25 luglio 1654 - 1728): Stabat mater a 6 voci, coro, archi e basso continuo (1728). Coro della Radio Svizzera, dir. Diego Fasolis; I Barocchisti, dir. René Clemencic.

Gerard Schwarz (1947): Variations on Greensleeves for violin and orchestra (2008). Maria Larionoff, violin; Seattle Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer.

Adolphe-Charles Adam (24 luglio 1803 - 1856): Ouverture per l’opéra-comique in 3 atti Si j’étais roi (1852). London Festival Orchestra, dir. Alfred Scholz.

Benedetto Marcello (24 luglio 1686 - 24 luglio 1739): Concerto in mi minore per violino, violoncello, archi e basso continuo op. 1 n. 2 (1708). Concerto Italiano, dir. Rinaldo Alessandrini.

Eduard Marxsen (23 luglio 1806 - 1887): Rondo brillant in fa maggiore per pianoforte op. 9. Anthony Spiri.

Eduard Marxsen (23 luglio 1806 - 1887): Rondo brillant in fa maggiore per pianoforte op. 9. Anthony Spiri.

Georges Auric (1899 - 23 luglio 1983): Sonata in sol maggiore per violino e pianoforte (1936). Frank Peter Zimmermann, violino; Alexander Lonquich, pianoforte.

Louis Abbiate (1866 - 23 luglio 1933): Concerto in re minore per violoncello e orchestra op. 35 (1895). Eliane Magnan, violoncello; Orchestre du Théâtre National de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, dir. Louis Frémaux.

Il compositore monegasco Louis Abbiate fu detto « il Paganini del violoncello », titolo attribuito in precedenza anche a Alfredo Piatti.

Aleksej Igudesman (22 luglio 1973) « ispirato da Ludwig van Beethoven »: For A Lease per 2 violini (2020). Julian Rachlin e Aleksej Igudesman.

Happy birthday, Aleksej! 🎻🍾🥂 🙂

Otmar Nussio (1902 - 22 luglio 1990): Variazioni per fagotto e archi sopra un tema di Pergolesi (1953). Stephanie Radon, fagotto; Ensemble Claronicum, dir. Leo Wittner.

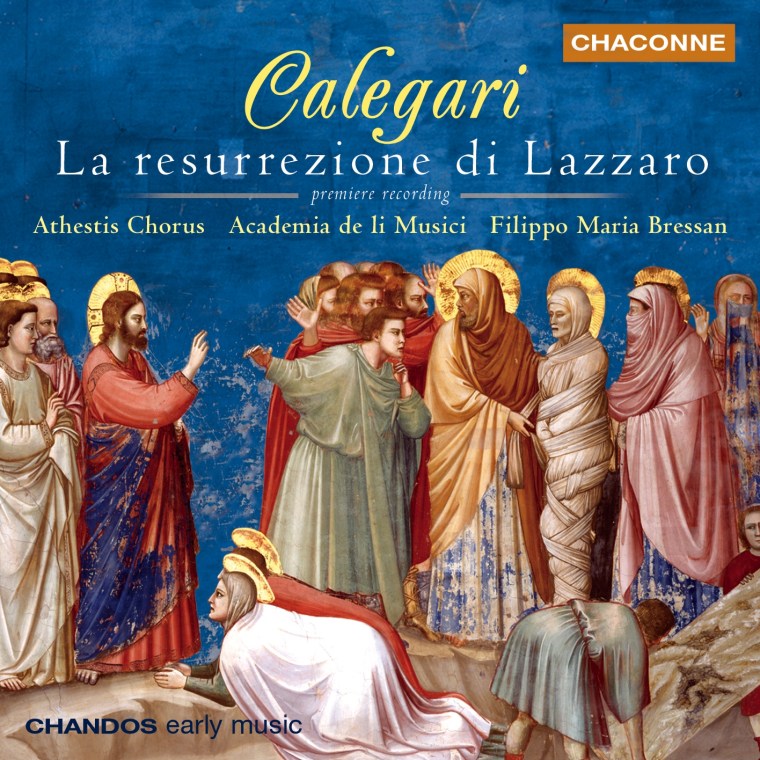

Antonio Calegari (1757 - 22 luglio 1828): La resurrezione di Lazzaro, oratorio (1779). Cristo: Roberta Giua, soprano; Tommaso: Luca Dordolo, tenore; Maddalena: Rosita Frisani, soprano; Marta: Manuela Custer, contralto; Lazzaro: Salvo Vitale, basso; coro Athestis; Academia de li Musici, dir. Filippo Maria Bressan.

Beauty and kindness

Franz Schubert (1797 - 1828): An Silvia, Lied for voice and piano op. 106 n. 4, D 891 (1826); lyrics by William Shakespeare (from The Two Gentlemen of Verona, act 4, scene 2), German translation by Eduard von Bauernfeld. Fritz Wunderlich, tenor; Hubert Giesen, piano.

|

Was ist Silvia, saget an,

Dass sie die weite Flur preist? Schön und zart seh’ ich sie nah’n, Auf Himmels Gunst und Spur weist, Dass ihr alles untertan. Ist sie schön und gut dazu? Darum Silvia, tön’, o Sang, |

Who is Silvia? what is she,

That all our swains commend her? Holy, fair, and wise is she; The heaven such grace did lend her, That she might admirèd be. Is she kind as she is fair? Then to Silvia let us sing, |

Charles E. Ives (1874-1954): Central Park in the Dark (1906). New York Philharmonic Orchestra, dir. Leonard Bernstein.

Charles E. Ives: The Unanswered Question (1908; revisione 1930-35). Stessi interpreti.

I due brani originariamente costituivano un’unica composizione in due parti con il titolo complessivo di Two Contemplations e quelli rispettivi di A Contemplation of Nothing Serious or Central Park in the Dark in «The Good Old Summer Time» e A Contemplation of a Serious Matter or The Unanswered Perennial Question.

Dietrich Buxtehude (1637 - 1707): La Capricciosa, aria in do maggiore con 32 variazioni BuxWV 250. Fernando De Luca, clavicembalo.

Mendelssohn’s Dream

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809 - 1847): Ein Sommernachtstraum, ouverture op. 21 (1826) and incidental music op. 61 (1842) for William Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Edith Mathis and Ursula Boese, sopranos; Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks and Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks conducted by Rafael Kubelík.

(In published scores, Overture and Finale are usually not numbered.)

Ouvertüre: Allegro vivace

ERSTER ELFE

Bunte Schlangen, zweigezüngt!

Igel, Molche, fort von hier!

Dass ihr euren Gift nicht bringt

In der Königin Revier!

Fort von hier!

ERSTER ELFE, ZWEITER ELFE UND CHOR

Nachtigall, mit Melodei

Sing in unser Eya popey!

Eya popey! Eya popey!

Dass kein Spruch,

Kein Zauberfluch,

Der holden Herrin schädlich sei.

Nun gute Nacht mit Eya popey!

ZWEITER ELFE

Schwarze Käfer,

Uns umgebt nicht mit Summen,

Macht euch fort!

Spinnen die ihr künstlich webt,

Webt an einem andern Ort!

ERSTER ELFE

Alles gut! Nun auf und fort!

Einer halte Wache dort!

Finale mit Chor: Allegro vivace [37:15]

CHOR DER ELFEN

Bei des Feuers mattem Flimmern,

Geister, Elfen, stellt euch ein!

Tanzet in den bunten Zimmern

Manchen leichten Ringelreihn!

Singt nach seiner Lieder Weise!

Singet! hüpfet lose, leise!

ERSTER ELFE (Solo)

Wirbelt mir mit zarter Kunst

Eine Not auf jedes Wort,

Hand in Hand, mit Feeengunst,

Singt und segnet diesen Ort!

CHOR DER ELFEN

Bei des Feuers mattem Flimmern,

Geister, Elfen, stellt euch ein!

Tanzet in den bunten Zimmern

Manchen leichten Ringelreihn!

Singt nach seiner Lieder Weise!

Singet! hüpfet lose, leise!

Nun genung,

Fort im Sprung,

Trefft ihn in der Dämmerung!

Carlo Boccadoro (20 luglio 1963): Soul Brother n. 1 per vibrafono, flauto, clarinetto basso, pianoforte, violino e violoncello (2011). Ensemble Sentieri selvaggi diretto dall’autore.

Witold Maliszewski (20 luglio 1873 - 18 luglio 1939): Sinfonia n. 1 in sol minore op. 8 (1904). Polska orkiestra radiowa, dir. Łukasz Borowicz.

Un altro compositore poco conosciuto ma oltremodo interessante. Stabilitosi in Polonia nel 1921, Maliszewski era nato in Ucraina (con il nomr di Vitol’d Osipovič Mališevskij) e si era diplomato al Conservatorio di San Pietroburgo; nel 1913 fu tra i fondatori del Conservatorio di Odessa.

Gabriele Agrimonti (1995): Improvisation on «Greensleeves». Performed by the composer on the Lewis Organ in Sotto il Monte Giovanni XXIII (Bergamo, Italy).

Günter Bialas (19 luglio 1907 - 18 luglio 1995): Introitus – Exodus per organo e orchestra (1976). Edgar Krapp, organo; Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, dir. Rafael Kubelík.

Alessio Prati (19 luglio 1750 - 1788): Concerto in la maggiore per fortepiano e archi. Antonella Cristiano, pianoforte; I Solisti Partenopei, dir. Ivano Caiazza.

English translation: please click here.

English translation: please click here.

Il suon d’argento

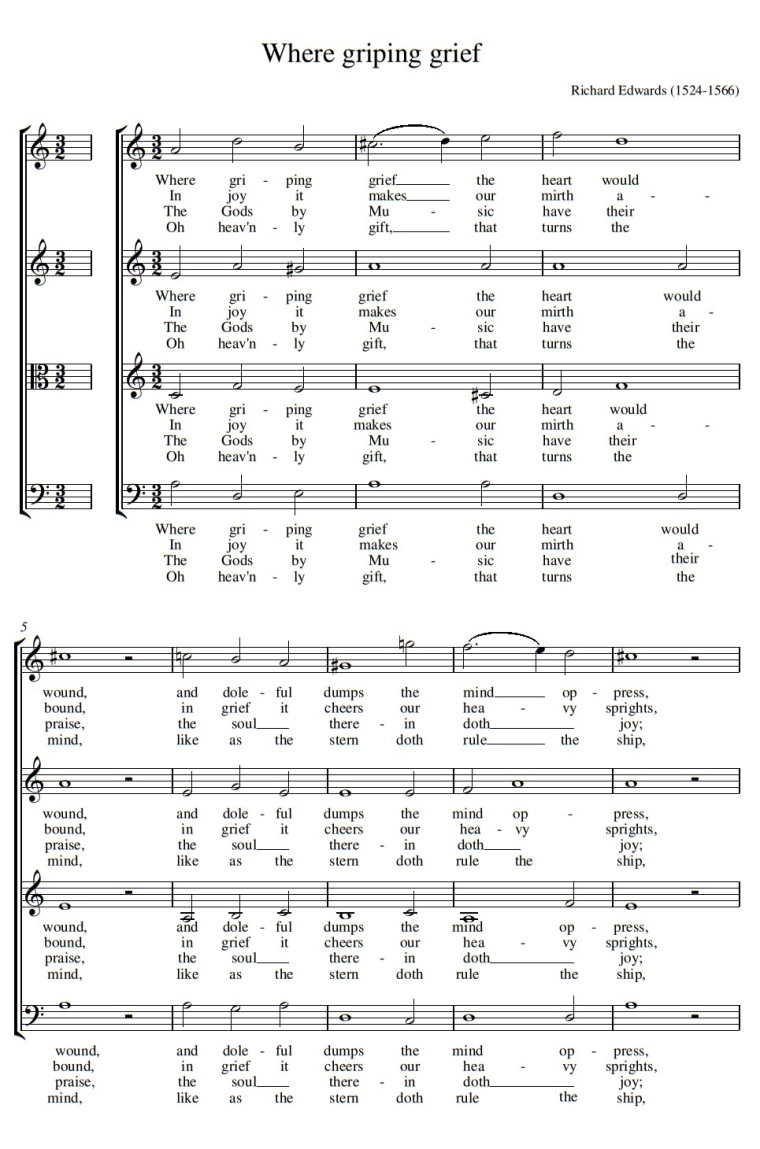

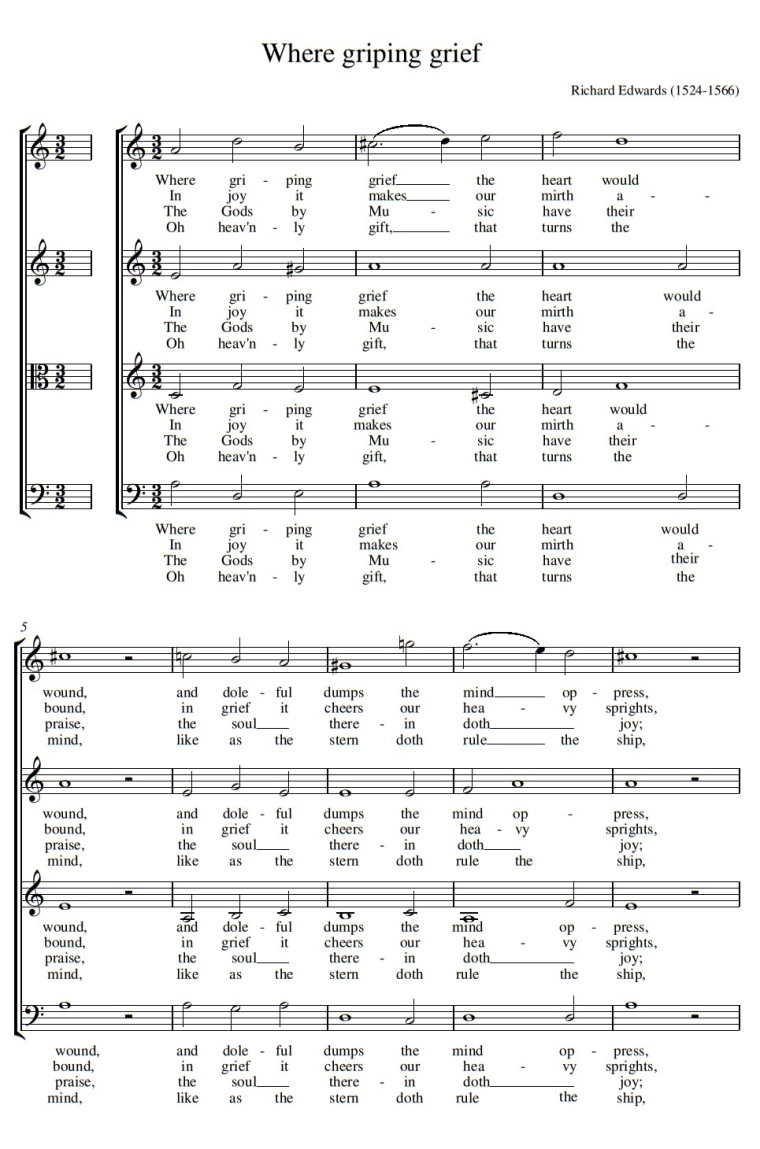

Anonimo (probabilmente Richard Edwardes, 1525 - 1566): Where griping grief. Versione per voce (soprano) e liuto: Emma Kirkby e Anthony Rooley. Versione a 4 voci: Deller Consort.

Where griping grief the heart would wound

And doleful dumps the mind oppress,

There music with her silver sound

Is wont with speed to give redress

Of troubled minds, for ev’ry sore,

Sweet music hath a salve in store.

In joy it makes our mirth abound,

In grief it cheers our heavy sprites,

The careful head relief hath found,

By music’s pleasant sweet delights;

Our senses, what should I say more,

Are subject unto Music’s law.

The gods by music have their praise,

The soul therein doth joy;

For as the Roman poets say,

In seas whom pirates would destroy,

A dolphin saved from death most sharp,

Arion playing on his harp.

O heavenly gift, that turns the mind,

Like as the stern doth rule the ship,

Of music whom the gods assigned,

To comfort man whom cares would nip,

Since thou both man and beast doth move,

What wise man then will thee reprove.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Del testo si trovano, anche nel web, numerose varianti, quasi tutte di poco conto, a cominciare da «When… Then…» invece di «Where… There…» nella prima strofa; ma è chiaramente un errore l’«Anon» che non di rado sostituisce «Arion» all’inizio dell’ultimo verso della terza strofa: Edwardes fa infatti riferimento a Arione di Métimna, l’antico citaredo che secondo Erodoto inventò il ditirambo e che, racconta il mito, si salvò da sicura morte in mare lasciandosi portare a riva da un delfino che aveva ammaliato con il canto.

Le due fonti manoscritte che ci hanno tramandato la musica di Where griping grief (il Mulliner Book, raccolta di composizioni per strumento a tastiera databile fra il 1550 e il 1585 circa; e il Brogyntyn Lute Book, c1595) non riportano né il testo né il nome dell’autore: si ritiene probabile che anche la musica sia dello stesso Edwardes. La melodia è finemente cesellata; pur procedendo prevalentemente per gradi congiunti, presenta non pochi intervalli più ampi, fra cui un’insolita (per l’epoca) ottava diminuita — sulle parole «dumps the» nel secondo verso della prima strofa.

Il brano doveva essere abbastanza noto all’epoca di Shakespeare, perché questi lo cita in una scena di Romeo e Giulietta. Alla fine del IV atto, dopo che la Nutrice ha rinvenuto il corpo esanime della giovane Capuleti e un cupo inatteso dolore strazia i suoi familiari, alcuni musicisti, che erano stati convocati per allietare la festa delle nozze di Giulietta con il conte Paride, ripongono mestamente gli strumenti e stanno per andarsene quando sopraggiunge Pietro (servitore della Nutrice) e chiede ai musici di suonare per lui; gli altri rispondono che non è il momento adatto per far musica, sicché Pietro inizia a battibeccare con loro e infine, citando Where griping grief, trova il modo di insolentirli. La scena consiste in una lunga serie di giochi di parole a sfondo musicale, da alcuni critici considerati di bassa lega — tanto che qualche traduttore italiano ha pensato bene di omettere l’intero passo. Ma secondo me la scena non è affatto priva di interesse, ragion per cui la riporto qui di seguito: a sinistra l’originale inglese, a destra non esattamente una traduzione, ma piuttosto una reinterpretazione, con alcune esplicite allusioni a musiche famose ai tempi del Bardo e già note ai frequentatori di questo blog.

|

PETER

Musicians, O musicians, Heart’s Ease, Heart’s Ease. O, an you will have me live, play Heart’s Ease. |

PIETRO

Musici, o musici, Chi passa, Chi passa. Se volete ch’io viva, suonate Chi passa. |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

Why Heart’s ease? |

1° MUSICO

Perché Chi passa? |

|

PETER

O musicians, because my heart itself plays My Heart is Full. O, play me some merry dump to comfort me. |

PIETRO

O musici, perché il mio cuore sta danzando un passamezzo che non passa. Prego, suonate qualche allegro lamento per confortarmi. |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

Not a dump, we. ‘Tis no time to play now. |

1° MUSICO

No, niente lamenti. Non è il momento di suonare. |

|

PETER

You will not then? |

PIETRO

Non volete suonare? |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

No. |

1° MUSICO

No. |

|

PETER

I will then give it you soundly. |

PIETRO

Allora ve le suonerò io, sentirete. |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

What will you give us? |

1° MUSICO

Che cosa sentiremo? |

|

PETER

No money, on my faith, but the gleek. I will give you the minstrel. |

PIETRO

Oh, non un tintinnar di monete, ve l’assicuro, ma piuttosto una canzon…atura. Ecco, vi tratterò da menestrelli. |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

Then I will give you the serving creature. |

1° MUSICO

E allora noi ti tratteremo da giullare. |

|

PETER

Then will I lay the serving creature’s dagger on your pate. I will carry no crotchets. I’ll re you, I’ll fa you. Do you note me? |

PIETRO

E allora riceverete la sonagliera del giullare sulla zucca. Vi avevo chiesto lamenti e mi date capricci. Così ve le suonerò: prendete nota. |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

An you re us and fa us, you note us. |

1° MUSICO

Se ce le suoni, prenderemo davvero le tue note. |

|

SECOND MUSICIAN

Pray you, put up your dagger and put out your wit. |

2° MUSICO

Per favore, riponi la tua sonagliera e va’ adagio. |

|

PETER

Then have at you with my wit. I will dry-beat you with an iron wit and put up my iron dagger. Answer me like men. (sings) When griping grief the heart doth wound And doleful dumps the mind oppress, Then Music with her silver sound— Why «silver sound»? Why «Music with her silver sound»? What say you, Simon Catling? |

PIETRO

Andrò a mio agio e vi metterò a disagio. I miei adagi non sono meno pesanti della sonagliera. Rispondete dunque, da uomini, ai miei colpi. (canta) Quando ferisce il cuore arduo tormento E la mente grava penoso tedio, Allora Musica dal suon d’argento… Perché «suon d’argento»? Perché dice «Musica dal suon d’argento»? Tu che ne dici, Simon Cantino? |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

Marry, sir, because silver hath a sweet sound. |

1° MUSICO

Diamine, signore, perché l’argento ha un dolce suono. |

|

PETER

Prates. What say you, Hugh Rebeck? |

PIETRO

Ciance. E tu che dici, Ugo Ribeca? |

|

SECOND MUSICIAN

I say, «silver sound» because musicians sound for silver. |

2° MUSICO

Dico: «suon d’argento» perché i musicisti suonano per guadagnarsi dell’argento. |

|

PETER

Prates too. What say you, James Soundpost? |

PIETRO

Ciance anche queste. E tu, Giaco Bischero? |

|

THIRD MUSICIAN

Faith, I know not what to say. |

3° MUSICO

In fede mia, non so che dire. |

|

PETER

Oh, I cry you mercy, you are the singer. I will say for you. It is «Music with her silver sound» because musicians have no gold for sounding. (sings) Then Music with her silver sound With speedy help doth lend redress. (exit) |

PIETRO

Oh, ti chiedo scusa: tu sei quello che canta. Be’, risponderò io per te: dice «Musica col suon d’argento» perché i musicisti non hanno mai oro da far risonare. (canta) Allora Musica dal suon d’argento Con lesto soccorso pone rimedio. (esce) |

|

FIRST MUSICIAN

What a pestilent knave is this same! |

1° MUSICO

Che pestifero furfante è costui! |

|

SECOND MUSICIAN

Hang him, Jack! Come, we’ll in here, tarry for the mourners and stay dinner. (exeunt) |

2° MUSICO

Lascialo perdere! Venite, entriamo: aspetteremo quelli che verranno per il funerale e ci fermeremo a pranzo. (escono) |

Her silver sound

Anonymous (probably Richard Edwardes, 1525 - 1566): Where griping grief. Two versions:

– as a song for 1 voice (soprano) and lute: Emma Kirkby and Anthony Rooley.

– as a partsong for 4 voices: the Deller Consort.

Where griping grief the heart would wound

And doleful dumps the mind oppress,

There music with her silver sound

Is wont with speed to give redress

Of troubled minds, for ev’ry sore,

Sweet music hath a salve in store.

In joy it makes our mirth abound,

In grief it cheers our heavy sprites,

The careful head relief hath found,

By music’s pleasant sweet delights;

Our senses, what should I say more,

Are subject unto Music’s law.

The gods by music have their praise,

The soul therein doth joy;

For as the Roman poets say,

In seas whom pirates would destroy,

A dolphin saved from death most sharp,

Arion playing on his harp.

O heavenly gift, that turns the mind,

Like as the stern doth rule the ship,

Of music whom the gods assigned,

To comfort man whom cares would nip,

Since thou both man and beast doth move,

What wise man then will thee reprove.

Richard Edwardes, possibly an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, was a poet, playwright, gentleman of the Chapel Royal and choirmaster of the same institution in the reigns of Mary and Elizabeth I. In his later years he compiled an extensive anthology of poems by various authors, adding his own, including Where griping grief (under the title In commendation of Musick). The anthology, titled The Paradise of Dainty Devices, appeared posthumously in 1576, edited by Henry Disle; it was the most successful of the numerous miscellaneous books printed at the end of the sixteenth century: it was in fact reprinted nine times in the following thirty years.

Richard Edwardes, possibly an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, was a poet, playwright, gentleman of the Chapel Royal and choirmaster of the same institution in the reigns of Mary and Elizabeth I. In his later years he compiled an extensive anthology of poems by various authors, adding his own, including Where griping grief (under the title In commendation of Musick). The anthology, titled The Paradise of Dainty Devices, appeared posthumously in 1576, edited by Henry Disle; it was the most successful of the numerous miscellaneous books printed at the end of the sixteenth century: it was in fact reprinted nine times in the following thirty years.

There are, even on the Internet, many variants of Where griping grief, almost all of little importance, such as for example «When… Then…» instead of «Where… There…» in the first line; but the «Anon» which often replaces «Arion» at the beginning of the last line of the third stanza is clearly a mistake: Edwardes in fact refers to Arion of Methymna, a kitharode in ancient Greece credited with inventing the dithyramb: according to the myth, Arion was saved from certain death at sea by being carried ashore by a dolphin that he had enchanted with his own singing.

The two manuscript sources that have handed down the music of Where griping grief (the Mulliner Book, a collection of pieces for keyboard instrument dating between about 1550 and 1585; and the Brogyntyn Lute Book, c1595) do not bear neither the text nor the name of the composer: the music is thought to be probably by Edwardes himself. Where griping grief has a finely chiseled tune; though proceeding mainly in joint degrees, it has several larger intervals, including an unusual (at that time) diminished octave — to the words «dumps the» in the second line of the first stanza.

Where griping grief must have been quite well known in Shakespeare’s time, so much so that its first stanza is quoted in a scene from Romeo and Juliet, at the end of the fourth act, after the Nurse has found the lifeless body of the young Capulet and a gloomy unexpected pain torments his relatives; the news also saddens some musicians, who had been summoned to cheer Juliet’s wedding party: they are putting away their instruments before leaving when Peter (the Nurse’s servant) asks them to play for him; since the musicians have no intention of pleasing him, Peter begins to argue with them and finally, quoting Where griping grief, finds a way to insult them.

PETER

Answer me like men.

(sings)

When griping grief the heart doth wound

And doleful dumps the mind oppress,

Then Music with her silver sound—

Why «silver sound»? Why «Music with her silver sound»? What say you, Simon Catling?

FIRST MUSICIAN

Marry, sir, because silver hath a sweet sound.

PETER

Prates. What say you, Hugh Rebeck?

SECOND MUSICIAN

I say, «silver sound» because musicians sound for silver.

PETER

Prates too. What say you, James Soundpost?

THIRD MUSICIAN

Faith, I know not what to say.

PETER

Oh, I cry you mercy, you are the singer. I will say for you. It is «Music with her silver sound» because musicians have no gold for sounding.

(sings)

Then Music with her silver sound

With speedy help doth lend redress.

(exit)

Fryderyk Chopin (1810 - 1849): Mazurka in fa diesis minore op. 6 n. 1 (1830-31). Arthur Rubinstein, pianoforte.

Il tono popolareggiante è posto subito in evidenza, con la caratteristica terzina che inizia ciascuna semifrase del primo tema; questo consiste di due periodi, uguali nella prima metà e differenti nella seconda, ed è ripetuto cinque volte: la prima ripetizione è immediata, mentre alle successive sono intercalati altri tre episodi, il secondo dei quali è una variante del primo. La struttura complessiva segue dunque lo schema AABAB’ACA. Nel tema A, all’inizio del secondo periodo è posta la didascalia «rubato»: questa indicazione ricorre in tutte le Mazurche delle prime raccolte, fino al secondo brano dell’op. 24.

Pauline Viardot-García (18 luglio 1821 - 1910): Plainte d’amour, sulla Mazurca op. 6 n. 1 di Chopin; testo di Louis Pomey. Marina Comparato, mezzosoprano; Elisa Triulzi, pianoforte.

Chère âme, sans toi j’expire,

Pourquoi taire ma douleur?

Mes lèvres veulent sourire

Mes yeux disent mon malheur.

Hélas! Loin de toi j’expire.

Que ma cruelle peine,

De ton âme hautaine

Désarme la rigueur.

Cette nuit dans un rêve,

Je croyais te voir;

Ah, soudain la nuit s’achève,

Et s’enfuit l’espoir.

Je veux sourire

Hélas! La mort est dans mon coeur.

Celebre mezzosoprano e compositrice, sorella della non meno famosa Maria Malibran, la Viardot fu allieva e amica di Chopin, che per lei nutrì sempre profonda stima e simpatia. Sembra che Fryderyk non disprezzasse affatto quel tipo di elaborazioni delle sue opere: alla Viardot espresse anzi il proprio gradimento. Pauline Viardot pubblicò due raccolte di Mazourkas de Chopin arrangées pour la voix, in tutto 12 brani, nel 1848.

NB: salvo diversa indicazione, i testi inseriti negli articoli dedicati a Chopin nel presente blog sono tratti dal volume Chopin: Signori il catalogo è questo di C. C. e Giorgio Dolza, Einaudi, Torino 2001.

Giovanni Bononcini (18 luglio 1670 - 1747): Il lamento d’Olimpia, cantata da camera per 1 voce, 2 violini e basso continuo (pubblicata in Cantate e duetti dedicati alla Sacra Maestà di Giorgio, re della Gran Bretagna, Londra 1721). Gloria Banditelli, contralto; Ensemble Aurora, dir. Enrico Gatti.

I. Preludio: Affettuoso – Allegro

II. Recitativo [3:32]

Le tenui rugiade

scotea dal carro d’or sull’erbe e i fiori

la rubiconda Aurora

allor ch’Olimpia, non ben desta ancora,

dell’amante infedele

vedova a un tratto ritrovò le piume.

Sciolse la tema dell’incerto danno

le reliquie del sonno in su i bei lumi;

e sospesa e tremante

dal lido al letto e dalla selva al lido,

chiamando il nome infido,

poiché più volte riportò le piante,

su la cima d’un sasso,

il guardo fisse entro l’aere dubbioso,

e, fra mille lamenti,

queste all’aure spiegò voci dolenti.

III. Aria: Affettuoso [4:48]

Vasto mar,

balze romite

deh mi dite,

il mio bene

ov’è, che fa.

Onde quiete,

aure serene

erbe, fiori,

ombrose piante,

il mio bene

se sapete,

rispondete

per pietà.

IV. Recitativo [8:47]

Lassa, che son la luce

la mia doglia s’avanza.

Io veggio, oh Dio, le gonfie

ingannatrici vele

dello sposo infedele

fuggir per l’acque, e portar lunge il vento

colla nave spergiura il mio lamento

Queste, Bireno ingrato,

son le promesse, il fido amore è questo?

Quanti, quanti pur dinanzi,

sotto il silenzio dell’ombrosa notte

e il tremolar delle invocate stelle,

giuramenti non fe’ d’esser costante!

Misera Olimpia, abbandonata amante,

in qual mente, in qual seno

più luogo avrà la vereconda fede,

s’io son schernita e m’ingannò Bireno?

V. Aria: Con spirito [10:20]

Quando dicea d’amarmi

allor volea lasciarmi

e mi tradiva allor.

Di mille inganni fabro

fede giurava il labro,

ed era infido il cor .

MacBallet

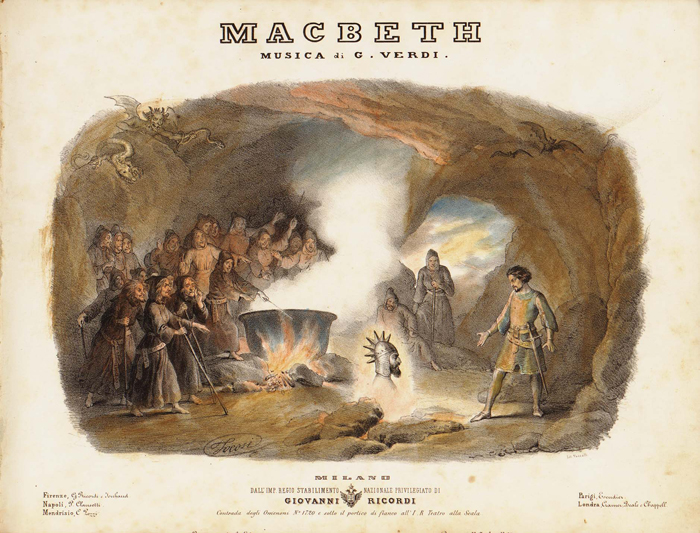

Giuseppe Verdi (1813 - 1901): Ballet music from Macbeth (1865). WDR Rundfunkorchester, dir. Massimo Zanetti.

Based on Shakespeare’s play of the same name, Verdi’s Macbeth was premiered on March 14th, 1847. The ballet scene was added to Verdi’s special Paris debut: the new version of the opera was first performed on April 21st, 1865.