Lady Greensleeves & Mistress Ford

Anonymous (second half of the sixteenth century, British): Greensleeves. Alfred Deller, countertenor; Desmond Dupre, lute.

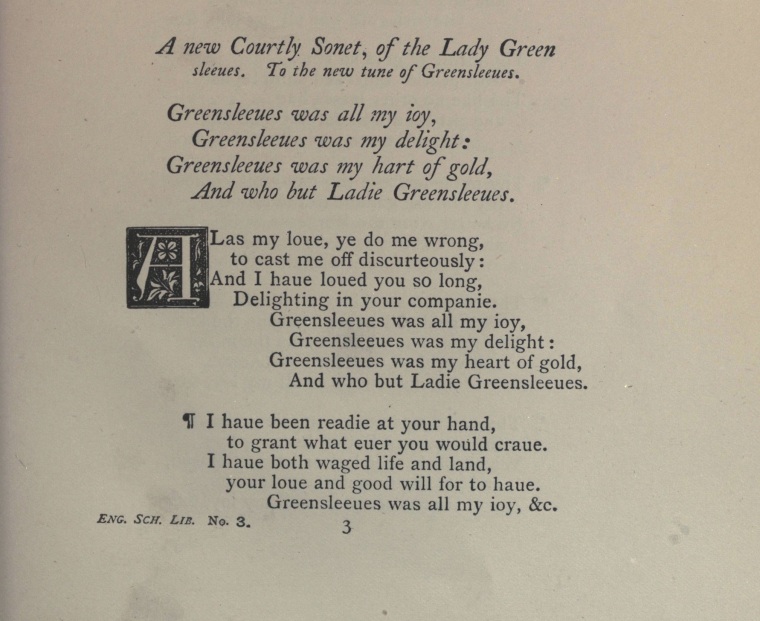

Deller’s interpretation gives us the opportunity to hear both the oldest known version of Greensleeves tune and some stanzas taken from the first known edition of the lyrics, a 1584 collection entitled A Handful of Pleasant Delites. Here is the full text (italicized stanzas are omitted by Deller):

Alas, my love, you do me wrong

To cast me off discourteously,

For I have loved you well and long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you would crave;

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and good-will for to have.

I bought three kerchers to thy head,

That were wrought fine and gallantly;

I kept them both at board and bed,

Which cost my purse well-favour’dly.

I bought thee petticoats of the best,

The cloth so fine as fine might be:

I gave thee jewels for thy chest;

And all this cost I spent on thee.

Thy smock of silk both fair and white,

With gold embroidered gorgeously;

Thy petticoat of sendall right;

And this I bought thee gladly.

Thy girdle of gold so red,

With pearls bedecked sumptously,

The like no other lasses had;

And yet you do not love me!

Thy purse, and eke thy gay gilt knives,

Thy pin-case, gallant to the eye;

No better wore the burgess’ wives;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thy gown was of the grassy green,

The sleeves of satin hanging by;

Which made thee be our harvest queen;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thy garters fringed with the gold,

And silver aglets hanging by;

Which made thee blithe for to behold;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

My gayest gelding thee I gave,

To ride wherever liked thee;

No lady ever was so brave;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

My men were clothed all in green,

And they did ever wait on thee;

All this was gallant to be seen;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

They set thee up, they took thee down,

They served thee with humility;

Thy foot might not once touch the ground;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

For every morning, when thou rose,

I sent thee dainties, orderly,

To cheer thy stomach from all woes;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

Thou couldst desire no earthly thing,

But still thou hadst it readily,

Thy music still to play and sing;

And yet thou wouldst not love me!

And who did pay for all this gear,

That thou didst spend when pleased thee?

Even I that am rejected here,

And thou disdainst to love me!

Well! I will pray to God on high,

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that, yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me!

Greensleeves, now farewell! Adieu!

God I pray to prosper thee!

For I am still thy lover true;

Come once again and love me!

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

Greensleeves cannot be missing from an anthology of Shakespearean music: the ballad of the beautiful green-sleeved lady is in fact mentioned twice in the comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor (first published in 1602, though believed to have been written in or before 1597). Its plot is well known: the pot-bellied and cash-strapped knight John Falstaff awkwardly tries to seduce two ladies, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, married to wealthy merchants living in Windsor (in Berkshire); by gaining their favour, Sir John hopes to fix his financial woe, but is quickly unmasked: the wives find he sent them identical love letters and take revenge by playing tricks on Falstaff.

When the hoax comes to light, Mistress Ford comments on the fact with these words (act 2, scene 1):

I shall think the worse of fat men, as long as I have an eye to make difference of men’s liking: and yet he would not swear; praised women’s modesty; and gave such orderly and well-behaved reproof to all uncomeliness, that I would have sworn his disposition would have gone to the truth of his words; but they do no more adhere and keep place together than the Hundredth Psalm to the tune of Green Sleeves.

It’s true: Psalm 100 does not adhere to Greensleeves; but it must be said that this is a purely metrical matter — the verses of the psalm («O be joyful in the Lord, all ye lands» according to the Great Bible, 1539) do not fit at all to the tune of the ballad — and not a sort of moral prohibition. Adapting a sacred text to a familiar secular melody (this is called contrafactum) has never been a problem, and we have already seen (click here) that Greensleeves itself has given its tune to a religious chant.

The last prank against Falstaff takes place in the forest of Windsor, where he is invited to go, dressed as a hunter, for a love rendezvous (act 5, scene 5). «Sir John!» says Mistress Ford, «Art thou there, my deer? my male deer?»; Falstaff replies by stating that «a tempest of provocation» will not be able to distract him from her, even if the sky thunders «to the tune of Green Sleeves»:

My doe with the black scut! Let the sky rain potatoes; let it thunder to the tune of Green Sleeves, hail kissing-comfits and snow eringoes; let there come a tempest of provocation, I will shelter me here.

(A few brief explanations:

– potatoes: when the potato was introduced to Europe, precisely at the time of Shakespeare, it was considered an aphrodisiac;

– kissing-comfits: perfumed sugar sweets, used to freshen the breath;

– eringoes: does not refer to the herbaceous plants of this name, but to the pleurotus eryngii, called king trumpet or king oyster mushroom, considered an aphrodisiac since ancient times.)

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.

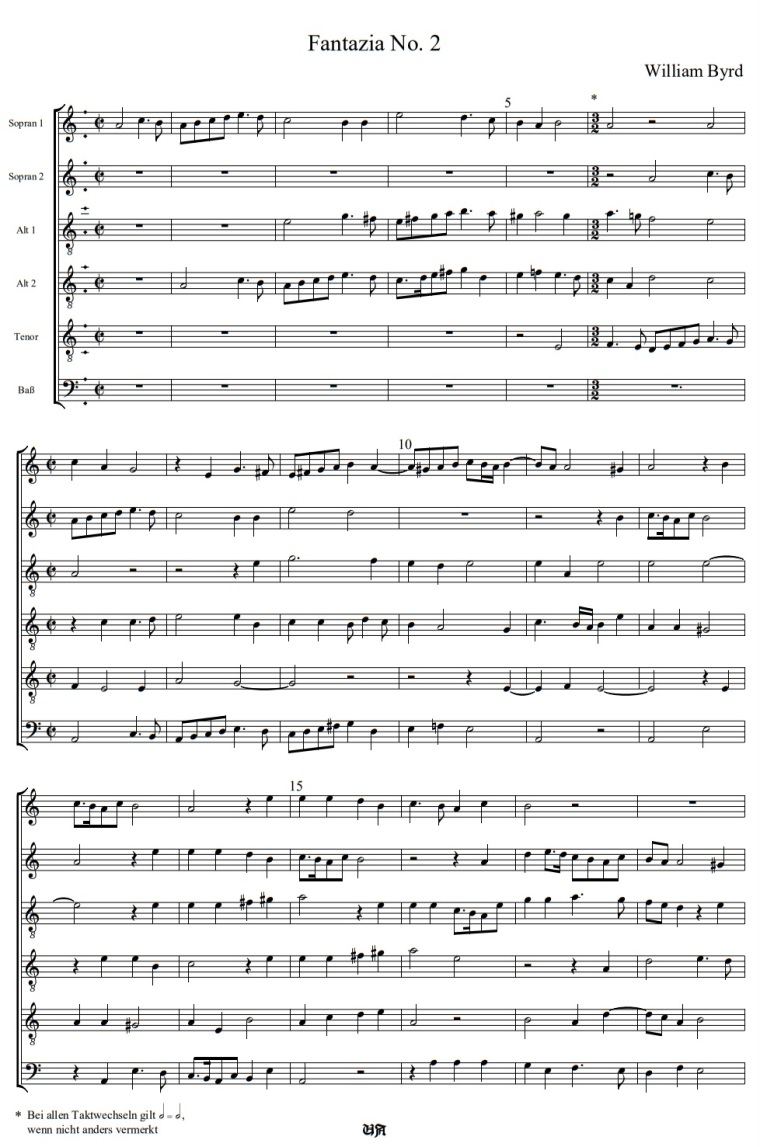

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.  Listening to these recercadas, perhaps Greensleeves will have come to your mind: there’s a reason, now we’ll see what it’s about.

Listening to these recercadas, perhaps Greensleeves will have come to your mind: there’s a reason, now we’ll see what it’s about.