Categoria: fumetti

Suonare in tedesco

Johann Sebastian Bach (31 marzo 1685 - 1750): «Schafe können sicher weiden», aria (n. 9) dalla cantata profana Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd BWV 208 (1713), trascrizione per pianoforte di Egon Petri (1881 - 1962). Julia Rinderle.

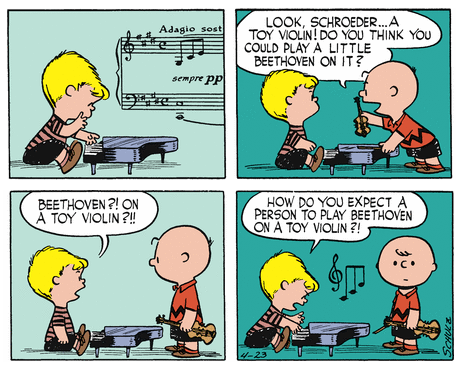

What is that you’re playing, Schroeder?

BWV 846, Schroeder & Maurizio Pollini.

Maurizio Pollini (5 gennaio 1942 - 23 marzo 2024)

Maurizio Pollini (5 gennaio 1942 - 23 marzo 2024)

Sinfonia a fumetti

Michael Daugherty (28 aprile 1954): Metropolis Symphony (1988–93). Nashville Symphony Orchestra, dir. Giancarlo Guerrero.

- Lex (1991)

- Krypton (1993) [10:03]

- MXYZPTLK (1988) [16:53]

- Oh, Lois! (1989) [23:55]

- Red Cape Tango (1993) [29:03]

I began composing my Metropolis Symphony in 1988, inspired by the celebration in Cleveland of the fiftieth anniversary of Superman’s first appearance in the comics. When I completed the score in 1993, I dedicated it to the conductor David Zinman, who had encouraged me to compose the work, and to the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. The Metropolis Symphony evokes an American mythology that I discovered as an avid reader of comic books in the fifties and sixties. Each movement of the symphony — which may be performed separately — is a musical response to the myth of Superman. I have used Superman as a compositional metaphor in order to create an independent musical world that appeals to the imagination. The symphony is a rigorously structured, non-programmatic work, expressing the energies, ambiguities, paradoxes, and wit of American popular culture. Like Charles Ives, whose music recalls small-town America early in our century, I draw on my eclectic musical background to reflect on late-twentieth-century urban America. Through complex orchestration, timbral exploration, and rhythmic polyphony, I combine the idioms of jazz, rock, and funk with symphonic and avant-garde composition.

I. Lex

« Lex » derives its title from one of Superman’s most vexing foes, the supervillain and business tycoon Lex Luthor. Marked “Diabolical” in the score, this movement features a virtuoso violin soloist (Lex) who plays a fiendishly difficult fast triplet motive in perpetual motion, pursued by the orchestration and a percussion section that includes four referee whistles placed quadraphonically on stage.

II. Krypton

« Krypton » refers to the exploding planet from which the infant Superman escaped. A dark, microtonal soundworld is created by glissandi in the strings, trombone, and siren. Two percussionists play antiphonal fire bells throughout the movement, as it evolves from a recurring solo motive in the cellos into ominous calls from the brass section. Gradually the movement builds toward an apocalyptic conclusion.

III. Mxyzptlk

« Mxyzptlk » is named after a mischievous imp from the fifth dimension who regularly wreaks havoc on Metropolis. This brightly orchestrated movement is the scherzo of the symphony, emphasizing the upper register of the orchestra. It features two dueling flute soloists who are positioned stereophonically on either side of the conductor. Rapidly descending and ascending flute runs are echoed throughout the orchestra, while open-stringed pizzicato patterns, moving strobe-like throughout the orchestra, are precisely choreographed to create a spatial effect.

IV. Oh, Lois!

« Oh, Lois! » invokes Lois Lane, news reporter at the Daily Planet alongside Clark Kent (alias Superman). Marked with the tempo “faster than a speeding bullet,” this five-minute concerto for the orchestra uses flexatone and whip to provide a lively polyrhythmic counterpoint that suggests a cartoon history of mishaps, screams, dialogue, crashes, and disasters, all in rapid motion.

V. Red Cape Tango

« Red Cape Tango » was composed after Superman’s fight to the death with Doomsday, and is my final musical work based on the Superman mythology. The principal melody, first heard in the bassoon, is derived from the medieval Latin death chant “Dies irae.” This dance of death is conceived as a tango, presented at times like a concertino comprising string quintet, brass trio, bassoon, chimes, and castanets. The tango rhythm, introduced by the castanets and heard later in the finger cymbals, undergoes a gradual timbral transformation, concluding dramatically with crash cymbals, brake drum, and timpani. The orchestra alternates between legato and staccato sections to suggest a musical bullfight.

Michael Daugherty

Divertimento in cui si esprime una uccellaja

Alessandro Speranza (24 aprile 1724 - 1797): Divertimento per cembalo in cui si esprime una uccellaja in sol maggiore. Falerno Ducande alias Fernando De Luca.

L’arte, perché

Il re e il liuto

John Dowland (1563 - 20 febbraio 1626): The King of Denmark’s Galliard (1605). Nigel North, liuto.

Nicht diese Küsse

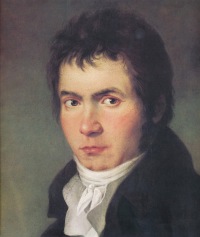

Ludwig van Beethoven (c16 dicembre 1770 - 1827): Der Kuß (Il bacio), arietta per voce e pianoforte op. 128 (1822) su testo di Christian Felix Weisse. Fritz Wunderlich, tenore; Hubert Giesen, pianoforte (in concerto, Festival di Salisburgo 1965).

Ich war bei Chloen ganz allein,

Und küssen wollt’ ich sie;

Jedoch sie sprach,

Sie würde schrein:

Es sei vergebne Müh’.

Ich wagt’ es doch und küßte sie,

Trotz ihrer Gegenwehr.

Und schrie sie nicht?

Jawohl, sie schrie,

Doch lange hinterher.

(Ero tutto solo con Cloe e volevo baciarla; ma lei disse che avrebbe gridato: fatica sprecata.

Osai ugualmente e la baciai, nonostante la sua riluttanza. E non gridò? Ma certo, gridò, però molto tempo dopo.)

16 dicembre 1970

Answering without answering

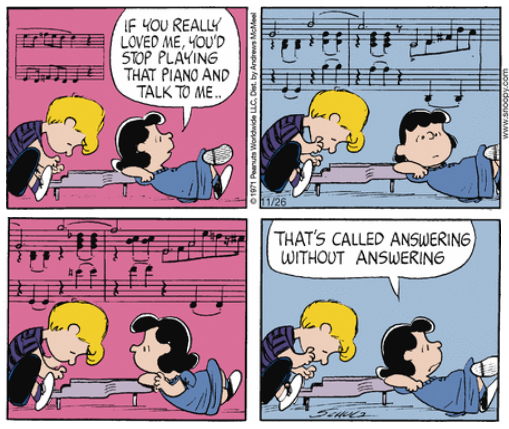

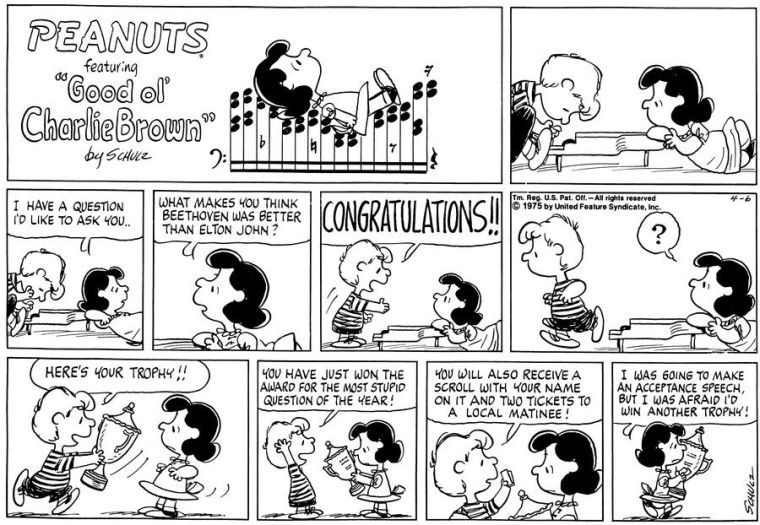

Lucy avrebbe potuto commentare «Ѐ come parlare a un sordo» ovvero «Non c’è peggior sordo di chi non vuol sentire», facendo esplicito riferimento al musicista più amato da Schroeder. Ma in effetti in questa striscia (del 29 novembre 1971) il piccolo virtuoso non esegue una composizione di Beethoven, bensì una delle più celebri creazioni di Chopin, la Ballata n. 1 in sol minore op. 23 (scritta forse nel 1835), che qui potete ascoltare nell’interpretazione di Krystian Zimerman:

Gopak

Aram Il’ič Chačaturjan (1903 - 1978): «Gopak», dal balletto Gajane (1942). Wiener Philharmoniker diretti dall’autore.

Pëtr Il’ič Čajkovskij (1840 - 1893): Gopak, dall’opera Mazeppa (atto I, scena 1a), rappresentata per la prima volta nel 1884. London Symphony Orchestra, dir. Geoffrey Simon.

Modest Musorgskij (1839 - 1881): Gopak, dall’opera comica La fiera di Soročynci (atto III, scena 2ª); Musorgskij ne scrisse il libretto (basato sull’omonimo racconto di Gogol’) e lavorò alla partitura fra il 1874 e il 1880, lasciandola però incompiuta. Eseguito da Katja Emec al violino, con orchestra non identificata (sopra), e dall’Orchestra sinfonica accademica di Stato dell’URSS diretta da Evgenij Svetlanov.

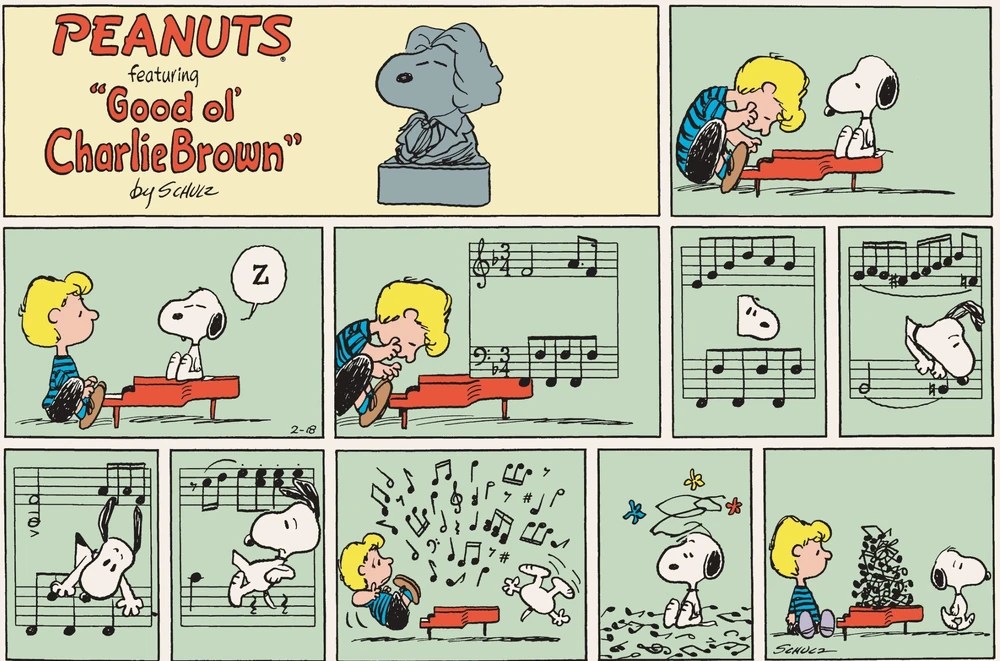

Nella tavola dei Peanuts (del 19 ottobre 1952) che apre questa pagina Charles Schulz ha inserito alcune battute tratte da una riduzione per pianoforte del Gopak di Musorgskij.

Toys

John Cage (1912 - 12 agosto 1992): Suite per pianoforte giocattolo (1948). Ju-Ping Song.

Folk songs: 12. Garyone

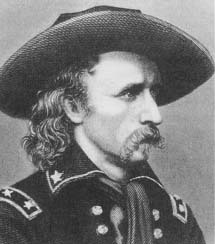

È possibile far sì che in un breve articoletto siano menzionati Ludwig van Beethoven, grande compositore tedesco nato a Bonn nel 1770, e George Armstrong Custer, famoso militare statunitense caduto in battaglia oltre cent’anni più tardi? Sì, è possibile se l’articolo è dedicato a Garyone, una canzone tradizionale irlandese (in Italia è però diffusa l’erronea convinzione che sia scozzese) le cui origini risalgono alla seconda metà del XVIII secolo.

È possibile far sì che in un breve articoletto siano menzionati Ludwig van Beethoven, grande compositore tedesco nato a Bonn nel 1770, e George Armstrong Custer, famoso militare statunitense caduto in battaglia oltre cent’anni più tardi? Sì, è possibile se l’articolo è dedicato a Garyone, una canzone tradizionale irlandese (in Italia è però diffusa l’erronea convinzione che sia scozzese) le cui origini risalgono alla seconda metà del XVIII secolo. Esperti linguisti assicurano che il titolo Garyone (anche Garyowen, Garryowen, Garry Owen, Garry Owens) sia derivato dalla locuzione irlandese garrai Eóins, ossia «il giardino di Eóin» (variante gaelica di John).

Esperti linguisti assicurano che il titolo Garyone (anche Garyowen, Garryowen, Garry Owen, Garry Owens) sia derivato dalla locuzione irlandese garrai Eóins, ossia «il giardino di Eóin» (variante gaelica di John).

Intorno al 1810, di Garyone Beethoven eseguì due diverse elaborazioni per canto, violino, violoncello e pianoforte, scritte su commissione di George Thomson (1757 – 1851), compositore e stampatore attivo a Edimburgo: questi aveva avviato un vasto progetto editoriale che prevedeva la pubblicazione di melodie tradizionali irlandesi, scozzesi e gallesi armonizzate e arrangiate da alcuni fra i più celebri musicisti dell’epoca: oltre a Beethoven, parteciparono all’impresa anche Franz Joseph Haydn e Johann Nepomuk Hummel.

Le due versioni beethoveniane di Garyone adottano un testo di tal Trevor Toms, From Garyone, my happy home ; edite a stampa nel 1814 e nel 1816, sono comprese nel catalogo delle opere di Beethoven fra le composizioni prive di numero d’opus (WoO = Werke ohne Opuszahl ) rispettivamente come WoO 152/22 e WoO 154/7.

WoO 152/22. Interpreti: Juliette Allen, soprano; Alessandro Fagiuoli, violino; Andrea Musto, violoncello; Jean-Pierre Armengaud, pianoforte.

WoO 154/7. Interpreti: Kerstin Wagner, contralto; Sachiko Kobayashi, violino; Chihiro Saito, violoncello; Michael Wagner, pianoforte.

From Garyone, my happy home,

Full many a weary mile I’ve come,

To sound of fife and beat of drum,

And more shall see it never.

‘Twas there I turn’d my wheel so gay,

Could laugh, and dance, and sing, and play,

And wear the circling hours away

In mirth or peace for ever.

But Harry came, a blithesome boy,

He told me I was all his joy,

That love was sweet, and ne’er could cloy,

And he would leave me never:

His coat was scarlet tipp’d with blue,

With gay cockade and feather too,

A comely lad he was to view;

And won my heart for ever.

My mother cried, dear Rosa, stay,

Ah! Do not from your parents stray;

My father sigh’d, and nought would say,

For he could chide me never:

Yet cruel, I farewell could take,

I left them for my sweetheart’s sake,

And came, ‘twas near my heart to break

From Garyone for ever.

Buit poverty is hard to bear,

And love is but a summer’s wear,

And men deceive us when they swear

They’ll love and leave us never:

Now sad I wander through the day,

No more I laugh, or dance, or play,

But mourn the hour I came away

From Garyone for ever.

Garyone ispirò anche Mauro Giuliani (1781 – 1829), che ne fece la prima delle sue 6 Arie nazionali irlandesi variate per chitarra op. 125 (c1827); qui è eseguita da William Carroll:

Diffusasi a Limerick nel tardo Settecento come canzone conviviale, Garyone ottenne rapidamente successo tra le file dell’esercito britannico, per il tramite del 5° Reggimento di lancieri (Royal Irish Lancers). Da allora fu adottata quale emblema musicale da numerose altre unità militari, suonata e cantata durante le guerre napoleoniche e poi in Crimea. Attraversò anche l’Oceano Atlantico e giunse negli Stati Uniti, dove nel 1851 fu scelta come canto di marcia dal 2° Reggimento di volontari irlandesi e più tardi dal 7° Reggimento di cavalleria, creato per affrontare le guerre indiane e affidato, fra gli altri, proprio a George Armstrong Custer. Una scena del film agiografico dedicato da Hollywood a questo discusso personaggio (They Died with Their Boots On, 1941, in Italia La storia del generale Custer ; la regia è di Raoul Walsh, protagonista Errol Flynn) racconta in modo romanzato l’episodio — come, del resto, tutta la storia:

We can dare or we can do

United men and brothers too

Their gallant footsteps to pursue

And change our country’s story.

Our hearts so stout have got us fame

For soon tis’ known from whence we came

Where’er we go they dread the name

Of Garryowen in glory.

And when the mighty day comes round

We still shall hear their voices sound

Our clans shall roar along the ground

For Garryowen in glory.

To emulate their high renown

To strike our false oppressor down

And stir the old triumphant sound

With Garryowen in glory.

Ricordando Quino

Premi

Peanuts, tavola domenicale del 6 aprile 1975

Changing rainbows

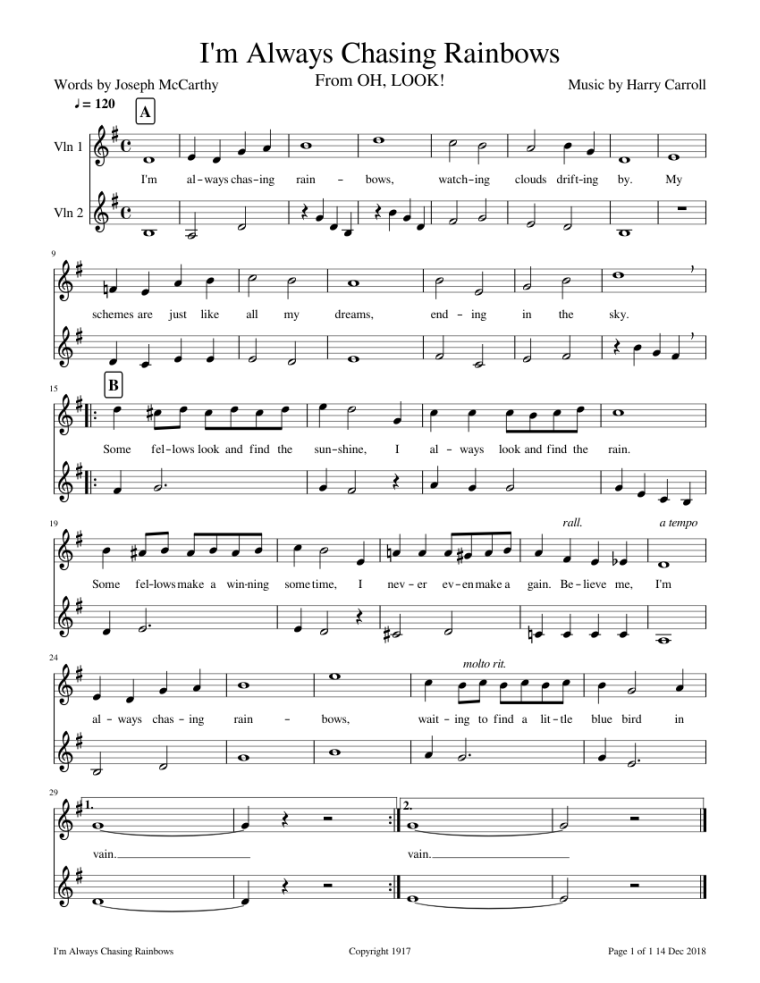

Questa strip dei Peanuts di Charles M. Schulz, pubblicata per la prima volta il 12 marzo 1968, contiene una spassosa allusione — spassosa in quanto la citazione di Lucy è errata — a un’espressione idiomatica inglese, la quale ha fra l’altro ispirato una nota canzone di music hall, I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.

Pubblicato nel 1917 come opera di Joseph McCarthy (testo) e Harry Carroll (musica), questo brano presenta qualche motivo di interesse per noi musicofili (o musicomani) in quanto è la prima canzone di Tin Pan Alley che sia stata composta utilizzando una melodia presa in prestito dal repertorio “classico”: si tratta del tema della sezione centrale (Moderato cantabile) della Fantaisie-impromptu in do diesis minore op. posth. 66 di Fryderyk Chopin.

Ecco I’m Always Chasing Rainbows cantata da Judy Garland nel film Le fanciulle delle follie (Zigfield Girl, 1941, regia di Robert Z. Leonard):

Artur Rubinstein per Chopin:

Tornando ai Peanuts, bisogna dire che l’impresa di rendere in italiano lo svarione di Lucy è tutt’altro che facile. Qui il traduttore se l’è cavata molto bene, facendo ricorso a un modo di dire ispirato dal capolavoro di Cervantes: