Lee Hoiby (17 febbraio 1926 - 2011): Winter Song per voce e pianoforte su testo di Wilfred Owen (n. 4 dei Songs for Leontyne; 1950, rev. 1983). Leontyne Price, soprano; David Garvey, pianoforte.

The browns, the olives, and the yellows died,

And were swept up to heaven; where they glowed

Each dawn and set of sun till Christmastide,

And when the land lay pale for them, pale-snowed,

Fell back, and down the snow-drifts flamed and flowed.

From off your face, into the winds of winter,

The sun-brown and the summer-gold are blowing;

But they shall gleam with spiritual glinter,

When paler beauty on your brows falls snowing,

And through those snows my looks shall be soft-going.

L’approfondimento

di Pierfrancesco Di Vanni

Vita e opere di Lee Henry Hoiby, alchimista della melodia

Lee Henry Hoiby è stato una figura centrale nel panorama musicale americano del Novecento. Compositore e pianista di eccezionale talento, egli ha dedicato la sua carriera alla celebrazione del lirismo e della forma classica, ponendosi spesso in controtendenza rispetto alle correnti avanguardistiche del suo tempo. Discepolo di Gian Carlo Menotti, ha lasciato un’eredità indelebile soprattutto nel campo dell’opera e della musica vocale.

Dalla tastiera alla penna: gli anni della formazione

Nato a Madison, nel Wisconsin, Hoiby dimostrò un talento precoce, iniziando a studiare pianoforte a soli cinque anni. La sua formazione fu di altissimo livello: studiò con celebri pianisti come Gunnar Johansen ed Egon Petri, per poi diventare allievo di Darius Milhaud al Mills College. Sebbene inizialmente fosse proiettato verso una carriera da concertista, l’incontro decisivo avvenne al Curtis Institute of Music con Gian Carlo Menotti: sotto la guida di questi, Hoiby non solo affinò le proprie doti di compositore, ma venne introdotto al mondo del teatro musicale, collaborando a produzioni di Broadway come The Consul. Nonostante le influenze dell’avanguardia del XX secolo (ebbe contatti con Harry Partch e il circolo di Schoenberg), il compositore scelse di abbracciare uno stile dichiaratamente lirico e comunicativo.

Il trionfo nel teatro d’opera

Il successo internazionale arrivò nel 1957 con la sua prima opera, The Scarf, presentata al Festival di Spoleto e acclamata dalla critica come un trionfo. Questo debutto aprì la strada a una serie di opere significative, tra cui Natalia Petrovna (1964), basata su Turgenev e oggi nota come A Month in the Country. Tuttavia, il suo capolavoro indiscusso rimane Summer and Smoke (1971), basato sul dramma di Tennessee Williams con libretto di Lanford Wilson. Tra le altre fatiche operistiche si annoverano la commedia Something New for the Zoo, il monologo musicale The Italian Lesson e l’adattamento della Tempesta di Shakespeare. La sua ultima opera, un adattamento di Romeo e Giulietta (2004), rimane una delle sue creazioni più acclamate dal pubblico internazionale.

L’ispirazione schubertiana e il legame con la voce

Oltre all’opera, Hoiby è celebrato come uno dei più grandi autori di canzoni (art songs) della sua epoca. Gran parte della sua popolarità in questo ambito si deve alla leggendaria soprano Leontyne Price, che portò al debutto molte delle sue arie. La filosofia compositiva del compositore era profondamente influenzata da Franz Schubert: dal maestro austriaco apprese l’importanza della linea melodica, del fraseggio e dell’economia nell’accompagnamento pianistico. Le sue composizioni vocali si distinguono per una meticolosa attenzione alla pronuncia delle vocali e al ritmo naturale del parlato, rendendo la musica un veicolo fluido per la poesia.

Gli ultimi anni

Nei suoi ultimi anni Hoiby continuò a esplorare nuovi linguaggi. Nel 2006 scrisse Last Letter Home, un brano toccante basato sulle ultime parole del soldato Jesse Givens, morto in Iraq, dimostrando una profonda sensibilità verso i temi contemporanei. Rivisitò inoltre i lavori giovanili, come la Summer Suite per banda, un progetto che egli stesso descrisse come «un regalo del me ventiseienne al me stesso attuale».

Il suo lascito comprende numerose composizioni corali (su testi di Walt Whitman e Richard Crashaw) che sono tuttora frequentemente eseguite negli Stati Uniti e nel Regno Unito, testimoniando la vitalità dell’approccio neoromantico di Hoiby alla musica moderna.

Winter Song

Uno fra i più significativi esempi del lirismo raffinato di Hoiby, composto originariamente nel 1950 e successivamente revisionato, fa parte della raccolta Songs for Leontyne, scritta appositamente per esaltare le caratteristiche uniche della voce della Price. Il testo di Wilfred Owen, solitamente noto per le sue poesie di guerra, qui si fa contemplativo e simbolico, offrendo al compositore il materiale per una composizione che oscilla tra il gelo invernale e una calda luminosità spirituale.

L’apertura stabilisce immediatamente un clima di sospensione eterea, con il pianoforte che introduce un disegno arpeggiato, fluido e quasi cristallino. Non è un inverno rigido e violento, ma un paesaggio ovattato, reso attraverso un’armonia tonale sofisticata e leggermente cromatica. Questi accordi spezzati suggeriscono il movimento del vento o la caduta lenta della neve, creando un tappeto sonoro su cui la voce può adagiarsi con estrema libertà.

Il soprano utilizza un registro centrale vellutato per descrivere la scomparsa dei colori autunnali («The browns, the olives, and the yellows died»). Hoiby scrive una linea vocale che asseconda perfettamente la prosodia del testo. Si nota l’utilizzo della tecnica della pittura sonora (word-painting): su «swept up to heaven», la linea vocale sale verso l’alto, riflettendo il movimento ascensionale dei colori che svaniscono, mentre su «glowed» si ha un’espansione del suono sia nel pianoforte che nella voce, preparando il culmine della prima sezione. Il finale della strofa («flamed and flowed») è magistrale: Price gestisce il crescendo con un controllo dinamico straordinario, mentre il pianoforte si fa più denso, quasi a voler rappresentare le fiammate del tramonto che si riflettono sulle distese di neve.

Dopo un breve interludio che mantiene la pulsazione costante, la poesia subisce uno scarto tematico: dalla natura si passa alla persona amata («From off your face…»). Hoiby traduce questo passaggio con una scrittura più intima e raccolta. La sezione centrale culmina sull’espressione chiave «spiritual glinter», dove la tessitura si sposta verso l’alto. Il soprano emette note acute che sembrano fluttuare nell’aria, private di ogni sforzo muscolare, incarnando perfettamente l’idea di uno “scintillio spirituale”. La bellezza fisica che sbiadisce (la «paller beauty» della vecchiaia o della sofferenza) viene trasfigurata in luce pura. Il punto di massima tensione emotiva coincide con il verso «When paler beauty on your brows falls snowing»: la voce della Price si espande nel suo registro più celebre, quello acuto e radioso, con una facilità d’emissione che rende la metafora della neve quasi tangibile.

Il finale è un esempio di assoluta maestria interpretativa e compositiva. Sull’ultimo verso, «my looks shall be soft-going», il compositore prescrive un pianissimo estremo. La voce esegue una nota finale che sembra svanire nel nulla, sostenuta da un ultimo accordo del pianoforte che lascia l’ascoltatore in uno stato di profonda pace meditativa.

Musicalmente, il pezzo dimostra come il compositore non cercasse la rottura con il passato, ma la continuità. L’influenza di Schubert è evidente nell’economia del materiale pianistico (la figura dell’arpeggio che persiste per quasi tutto il brano), mentre la sensibilità armonica guarda al neoromanticismo americano.

Nel complesso, questa composizione evidenzia il perfetto connubio tra scrittura vocale, rapporto testo-musica e struttura formale: Hoiby scrive infatti “attorno” alla voce di Leontyne Price, conoscendone perfettamente i punti di forza (il registro acuto lucente e il centro più cupo) e ogni immagine poetica di Owen trova un rispettivo armonico o melodico preciso. Infine, nonostante la forma libera, il brano ha una coerenza interna fortissima, data dal costante ritorno della figurazione pianistica iniziale, che funge da elemento unificatore del “paesaggio invernale”.

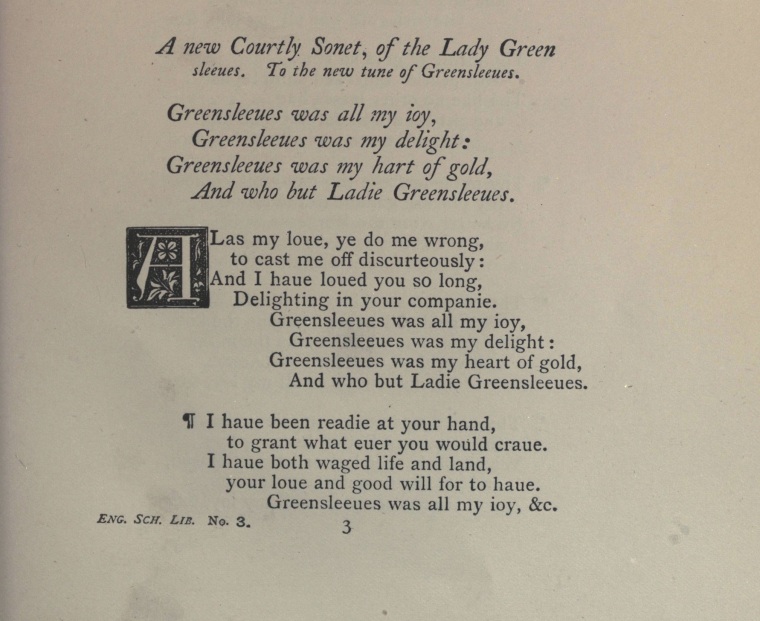

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

English translation: please

English translation: please  Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Dopo aver ascoltato

Dopo aver ascoltato