Niccolò Castiglioni (17 luglio 1932 - 1996): Hymne per 12 voci a cappella (1989) su testo tratto dallo Stabat mater di Jacopone da Todi. Schola Cantorum Stuttgart, dir. Clytus Gottwald.

Niccolò Castiglioni (17 luglio 1932 - 1996): Hymne per 12 voci a cappella (1989) su testo tratto dallo Stabat mater di Jacopone da Todi. Schola Cantorum Stuttgart, dir. Clytus Gottwald.

Jean-Frédéric Edelmann (1749 - ghigliottinato il 17 luglio 1794): Sonata in do minore op. 2 n. 1 (1775). Sylvie Pécot-Douatte (1957 - 2004), clavicembalo.

Fiorenzo Maschera (1541 - 16 luglio 1584): Canzon alla francese «La Capriola» a 4 voci (pubblicata in Libro Primo de canzoni da sonare, 1582, n. 1). Liuwe Tamminga, organo.

Goffredo Petrassi (16 luglio 1904 - 2003): Sonata da camera per clavicembalo e 10 strumenti (1948). Francesco Massimi, clavicembalo; Ensemble OTLIS, dir. Carlo Palleschi.

Sir James MacMillan (16 luglio 1959): The Gallant Weaver per coro a cappella (1997) su testo di Robert Burns. The Sixteen, dir. Harry Christophers

Where Cart rins rowin’ to the sea,

By mony a flower and spreading tree,

There lives a lad, the lad for me,

He is a gallant Weaver.

O, I had wooers aught or nine,

They gied me rings and ribbons fine;

And I was fear’d my heart wad tine,

And I gied it to the Weaver.

My daddie sign’d my tocher-band,

To gie the lad that has the land,

But to my heart I’ll add my hand,

And give it to the Weaver.

While birds rejoice in leafy bowers,

While bees delight in opening flowers,

While corn grows green in summer showers,

I love my gallant Weaver.

Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani (15 luglio 1638 - p1692): Beatus vir (Salmo 111) per basso e strumenti (pubblicato in Salmi, Mottetti e Litanie della B. V. a 1. 2. 3. voci op. V, 1688). Markus Flaig, basso; ensemble Vita & Anima, dir. Peter Waldner.

Jane Vieu (15 luglio 1781 - 1955): Sérénade japonaise, mélodie (1903) su testo di Serge Rello. Katherine Eberle, mezzosoprano; Robin Guy, pianoforte.

Mets ta robe d’azur,

Chausse tes pieds fragiles.

Près du bambou flexible

Une source frémit:

Les étoiles s’y mirent,

En des sursauts fébriles,

Comme des yeux de femme

Aux yeux de leur ami!

Viens, Taïmu, descends,

La rosée est divine,

Clair joyau sous la lune

A l’opalin baiser;

Je voudrais l’accrocher

A ta blonde poitrine

Et la prendre à tes cils,

Pour aller m’en griser.

Mets ta robe d’azur…

La lune de cristal

Fait la nature bléme,

C’est l’heure du silence ému!

Le cœur s’écoute mieux!

Il semble que tout s’aime!

Aimons nous! douce Taïmu!

Mets ta robe d’azur…

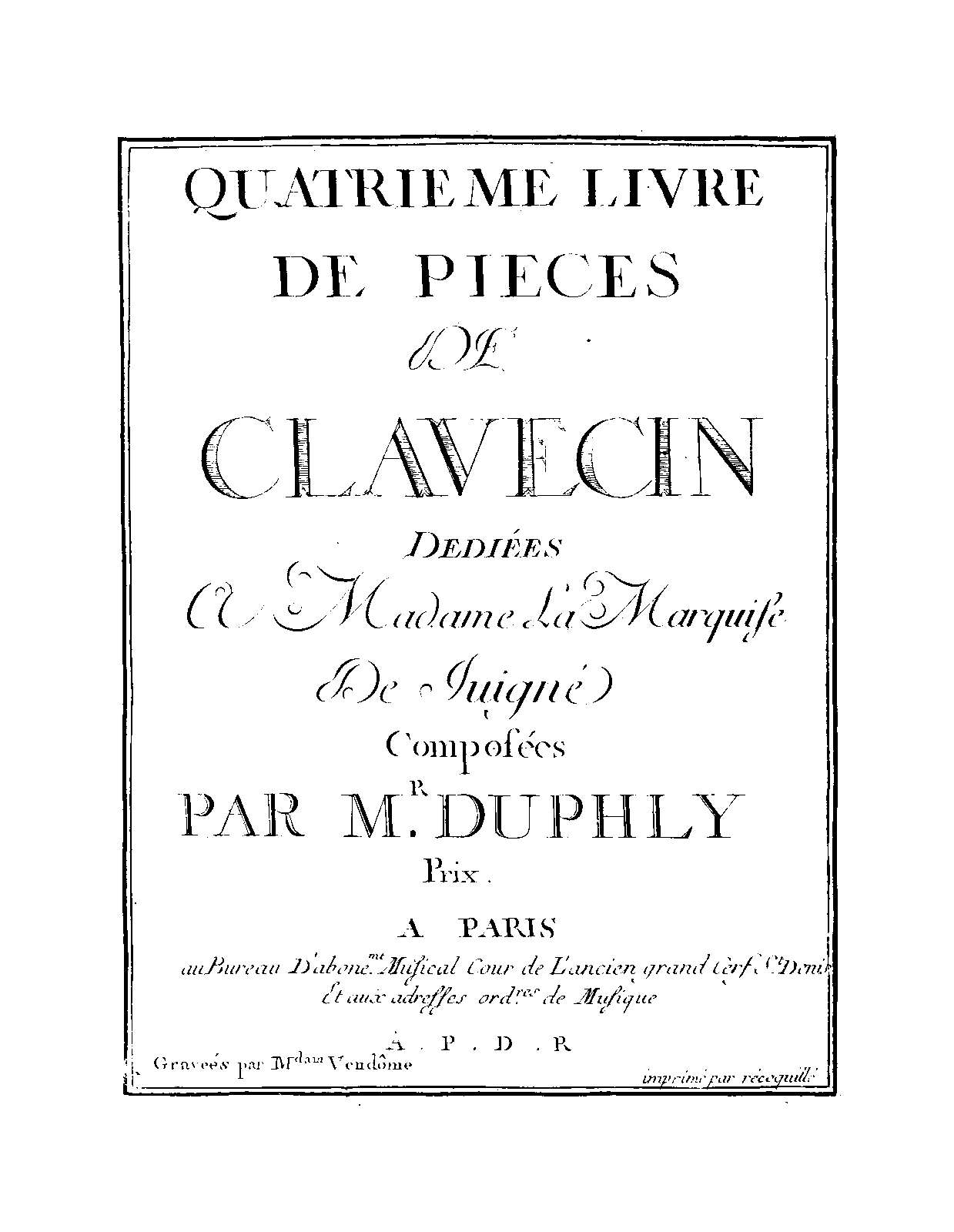

Jacques Duphly (1715 - 15 luglio 1789): Quatrième Livre de Pièces de Clavecin (1768). Pieter-Jan Belde, clavicembalo.

Diego Ortiz (c1510 - c1570): Recercada quinta sobre el passamezzo antiguo: Zarabanda, dal Tratado de glosas (trattato sulle variazioni, 1553). Hespèrion XXI, dir. e viola da gamba Jordi Savall.

Diego Ortiz: Recercada VII sobre la romanesca. Stessi interpreti.

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.

Passamezzo e romanesca sono danze in voga nel Cinquecento e nei primi anni del secolo successivo. Il passamezzo, di origine italiana, ha andamento lievemente mosso e ritmo binario; sotto il profilo coreutico è molto affine alla pavana, tanto che non di rado, all’epoca, viene con questa identificato: nell’Orchésographie (1588), Thoinot Arbeau scrive che il passamezzo è «une pavane moins pesamment et d’une mesure plus légière». La musica del passamezzo si fonda sopra uno schema armonico caratteristico, non molto dissimile da quello della follia; i musicisti europei tardorinascimentali se ne innamorano e l’impiegano quale base di serie di variazioni e di composizioni vocali: fra gli esempi più celebri vi sono The Oak and the Ash e, appunto, Greensleeves.

Intorno alla metà del Cinquecento, lo schema armonico del passamezzo dà origine a una variante destinata a avere altrettanta fortuna: viene chiamata passamezzo moderno per distinguerla dall’altra, detta conseguentemente passamezzo antico. Nella seconda parte del secolo, a fianco di passamezzo antico e passamezzo moderno entrano nell’uso altre formule armoniche stilizzate, come per esempio quella detta romanesca, dal nome di una danza affine alla gagliarda, di origine forse italiana o forse spagnola. Lo schema della romanesca è quasi identico a quello del passamezzo antico, da cui differisce solo per l’accordo iniziale.

La più antica versione nota di Greensleeves, che risale agli anni ’80 del XVI secolo, si fonda sul passamezzo antico, ma nel volgere di breve tempo viene soppiantata da una variante che adotta il basso della romanesca. Quasi certamente è quest’ultima la versione conosciuta da Shakespeare, il quale per due volte fa riferimento alla «melodia di Greensleeves» nella commedia Le allegre comari di Windsor (ce ne occuperemo presto). La versione originale, identificata nell’Ottocento dal musicografo inglese William Chappell (cui si deve la raccolta Popular Music of the Olden Time, 1855-59), è oggi la più nota e diffusa.

Listening to these recercadas, perhaps Greensleeves will have come to your mind: there’s a reason, now we’ll see what it’s about.

Listening to these recercadas, perhaps Greensleeves will have come to your mind: there’s a reason, now we’ll see what it’s about.

Passamezzo and romanesca were popular dances in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The passamezzo has Italian origins, slightly fast movement and binary rhythm; the dance is very similar to the pavana, so that in 16th century it was often identified with it: in his treatise Orchésographie (1588) Thoinot Arbeau asserts that the passamezzo is «une pavane moins pesamment et d’une mesure plus légière». The music of the passamezzo is based on a characteristic harmonic pattern, similar to that of the follia; late Renaissance European musicians fell in love with it and used it as a ground for sets of variations and for singing poetry: among the most famous examples are The Oak and the Ash and, precisely, Greensleeves.

Around the middle of the sixteenth century, the harmonic formula of the passamezzo gave rise to a variant that was equally successful: it was called passamezzo moderno to distinguish it from the other, consequently called passamezzo antico. During the second half of the century, alongside the passamezzo antico and moderno, other stylized harmonic formulas came into use, such as for example the romanesca, which took its name from a dance similar to the gagliarda, of Italian or perhaps Spanish origin. The pattern of the romanesca is almost identical to that of the passamezzo antico, from which it differs only in the first chord.

The earliest known version of Greensleeves, dating from about 1580, is based on the passamezzo antico ground, but was soon superseded by a variant adopting the harmonic formula of the romanesca. The latter is almost certainly the version known from Shakespeare, who refers twice to «the tune of Greensleeves» in the play The Merry Wives of Windsor (which we will deal with soon). The original version, identified in the 19th century by the English musicographer William Chappell (who published the collection Popular Music of the Olden Time, 1855-59), is today the best known and most widespread.

Unsuk Chin (14 luglio 1961): Allegro ma non troppo per percussionista e nastro magnetico (1994-98). Solista Ying-Hsueh Chen.

Unsuk Chin: Toccata (Studio per pianoforte n. 5, 2003). Mei Yi Foo, pianoforte.

Unsuk Chin: Mad Tea-Party Ouverture dall’opera Alice in Wonderland (libretto di David Henry Hwang, da Lewis Carroll; 2007). Orchestra Filarmonica di Seul, dir. Myung-Whun Chung.

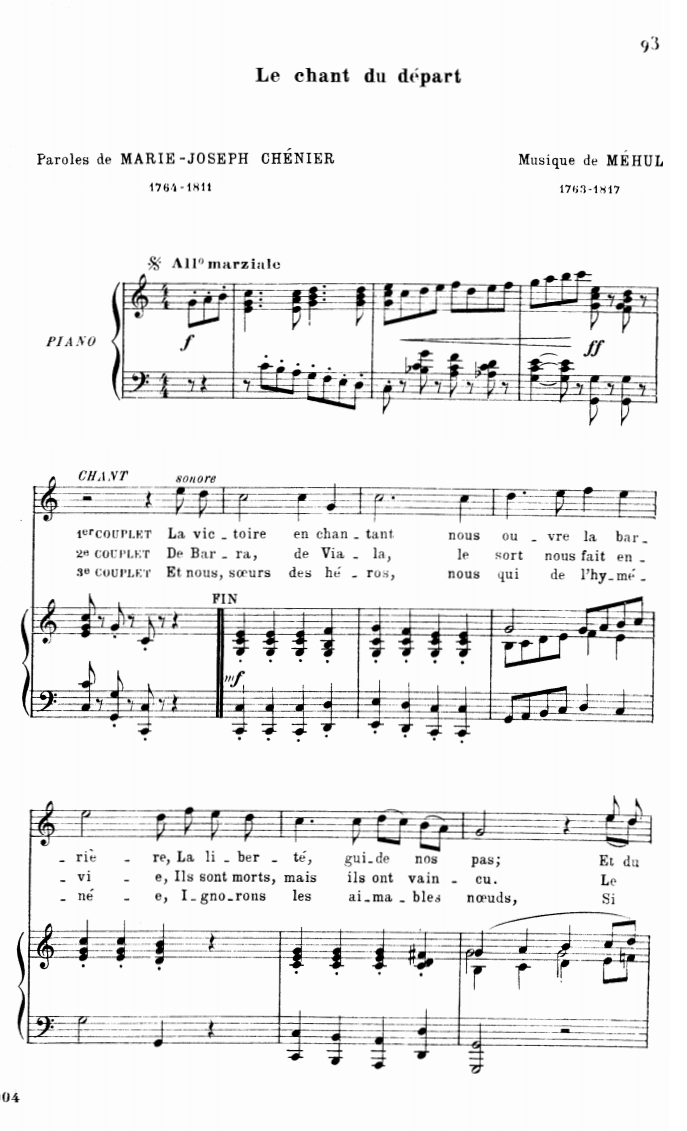

Étienne-Nicolas Méhul (1763 - 1817): Le Chant du départ (originariamente Hymne de la liberté) per voci soliste, coro e orchestra (1794) su testo di Marie-Joseph Chénier (1764 - 1811). Versione con orchestra di strumenti a fiato e timpani: Antonella Balducci, soprano; Dennis Hall, baritono; Coro e Orchestra della Radiotelevisione della Svizzera italiana, dir. Herbert Handt.

Le Chant du départ (testo completo)

La victoire en chantant nous ouvre la barrière.

La liberté guide nos pas.

Et du Nord au Midi, la trompette guerrière

A sonné l’heure des combats.

Tremblez, ennemis de la France,

Rois ivres de sang et d’orgueil!

Le Peuple souverain s’avance;

Tyrans descendez au cercueil.

Chant des guerriers (refrain):

La République nous appelle:

Sachons vaincre ou sachons périr.

Un Français doit vivre pour elle,

Pour elle un Français doit mourir.

Une mère de famille :

De nos yeux maternels ne craignez pas les larmes:

Loin de nous de lâches douleurs!

Nous devons triompher quand vous prenez les armes:

C’est aux rois à verser des pleurs.

Nous vous avons donné la vie,

Guerriers, elle n’est plus à vous;

Tous vos jours sont à la patrie:

Elle est votre mère avant nous.

(refrain)

Deux vieillards :

Que le fer paternel arme la main des braves;

Songez à nous au champ de Mars;

Consacrez dans le sang des rois et des esclaves

Le fer béni par vos vieillards;

Et, rapportant sous la chaumière

Des blessures et des vertus,

Venez fermer notre paupière

Quand les tyrans ne seront plus.

(refrain)

Un enfant :

De Barra, de Viala le sort nous fait envie;

Ils sont morts, mais ils ont vaincu.

Le lâche accablé d’ans n’a point connu la vie:

Qui meurt pour le peuple a vécu.

Vous êtes vaillants, nous le sommes:

Guidez-nous contre les tyrans;

Les républicains sont des hommes,

Les esclaves sont des enfants.

(refrain)

Une épouse :

Partez, vaillants époux: les combats sont vos fêtes.

Partez, modèles des guerriers:

Nous cueillerons des fleurs pour en ceindre vos têtes.

Nos mains tresseront vos lauriers.

Et, si le temple de mémoire

S’ouvrait à vos mânes vainqueurs,

Nos voix chanteront votre gloire,

Nos flancs porteront vos vengeurs.

(refrain)

Une jeune fille :

Et nous, sœurs des héros, nous qui de l’hyménée

Ignorons les aimables nœuds,

Si, pour s’unir un jour à notre destinée,

Les citoyens forment des vœux,

Qu’ils reviennent dans nos murailles

Beaux de gloire et de liberté,

Et que leur sang, dans les batailles,

Ait coulé pour l’égalité.

(refrain)

Trois guerriers :

Sur le fer devant Dieu, nous jurons à nos pères,

À nos épouses, à nos sœurs,

À nos représentants, à nos fils, à nos mères,

D’anéantir les oppresseurs:

En tous lieux, dans la nuit profonde,

Plongeant l’infâme royauté,

Les Français donneront au monde

Et la paix et la liberté.

(refrain)

A Fool’s Song

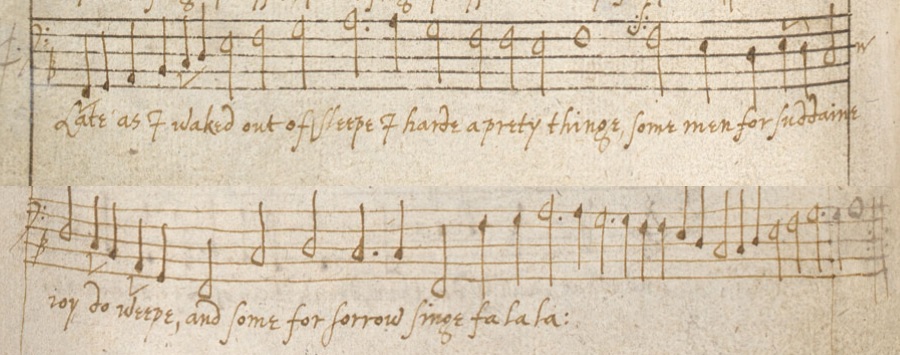

Anonymous (16th century): Then they for sudden joy did weep, Fool’s song from the 1st act, scene 4, of Shakespeare’s King Lear (1605-06). The Deller Consort.

Then they for sudden joy did weep

And I for sorrow sung.

Louis Ganne (1862 - 13 luglio 1923): Andante et Scherzo per flauto e pianoforte (1901). Michel Debost, flauto; Christian Ivaldi, pianoforte.

Asger Hamerik (1843 - 13 luglio 1923): Quinta Sinfonia in sol minore op. 36, Symphonie sérieuse (1889–91). Helsingborgs Symfoniorkester, dir. Thomas Dausgaard.

Asger Hamerik (1843 - 13 luglio 1923): Quinta Sinfonia in sol minore op. 36, Symphonie sérieuse (1889–91). Helsingborgs Symfoniorkester, dir. Thomas Dausgaard.

When my love swears

Oscar van Hemel (1892 - 1981): Four Shakespeare sonnets for mixed choir (1961). Vocaal Ensemble PANiek.

Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy.

Why lovest thou that which thou receivest not gladly,

Or else receivest with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tunèd sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering,

Resembling sire and child and happy mother,

Who, all in one, one pleasing note do sing.

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: «Thou single wilt prove none».

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell;

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it; for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O, if (I say) you look upon this verse,

When I (perhaps) compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love even with my life decay,

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

The little Love-god lying once asleep,

Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand,

Whilst many nymphs that vowed chaste life to keep

Came tripping by; but in her maiden hand

The fairest votary took up that fire

Which many legions of true hearts had warmed;

And so the General of hot desire

Was, sleeping, by a virgin hand disarmed.

This brand she quenched in a cool well by,

Which from Love’s fire took heat perpetual,

Growing a bath and healthful remedy,

For men diseased; but I, my mistress’ thrall,

Came there for cure and this by that I prove,

Love’s fire heats water, water cools not love.

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

Oh, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

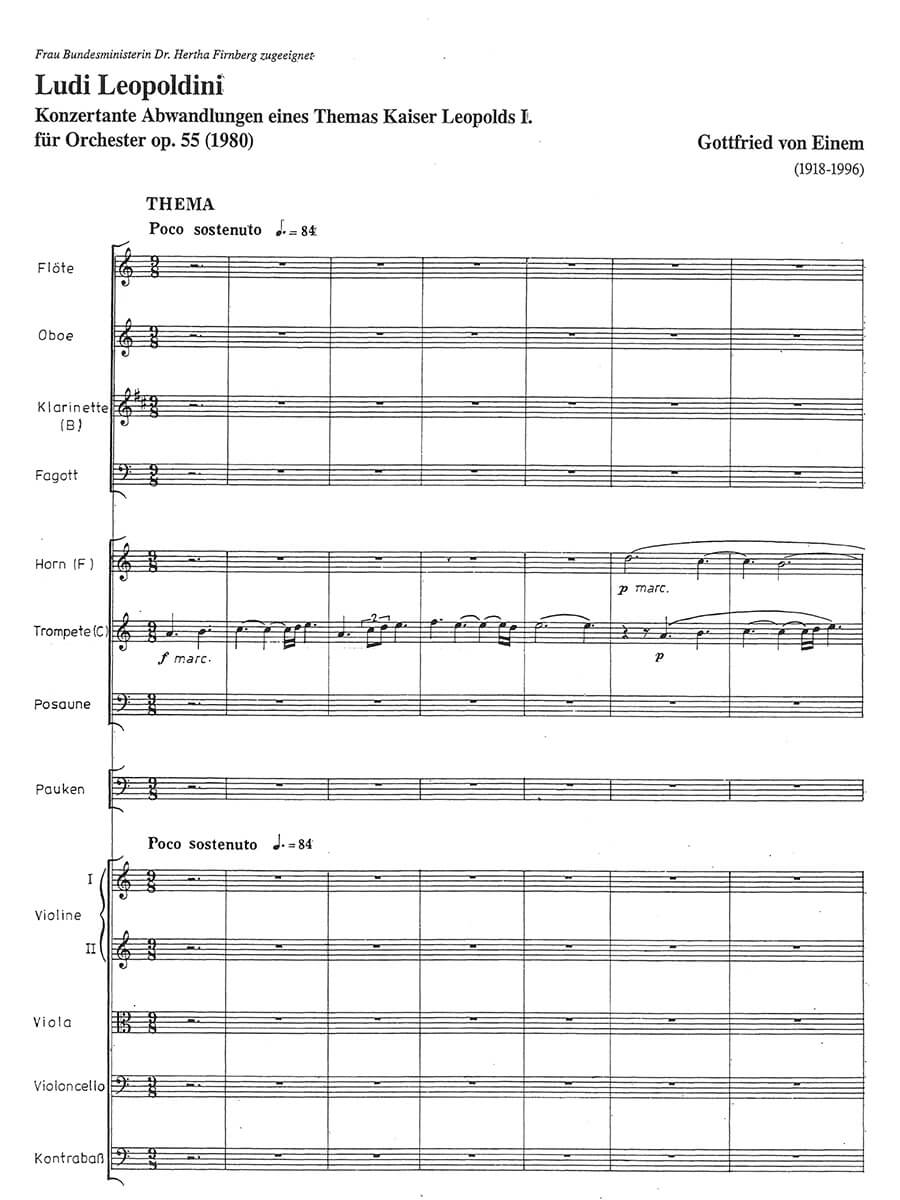

Gottfried von Einem (1918 - 12 luglio 1996): Ludi Leopoldini, variazioni concertanti per orchestra op. 55 sopra un tema dell’imperatore Leopoldo I (1980). Wiener Symphoniker, dir. Wolfgang Sawallisch.

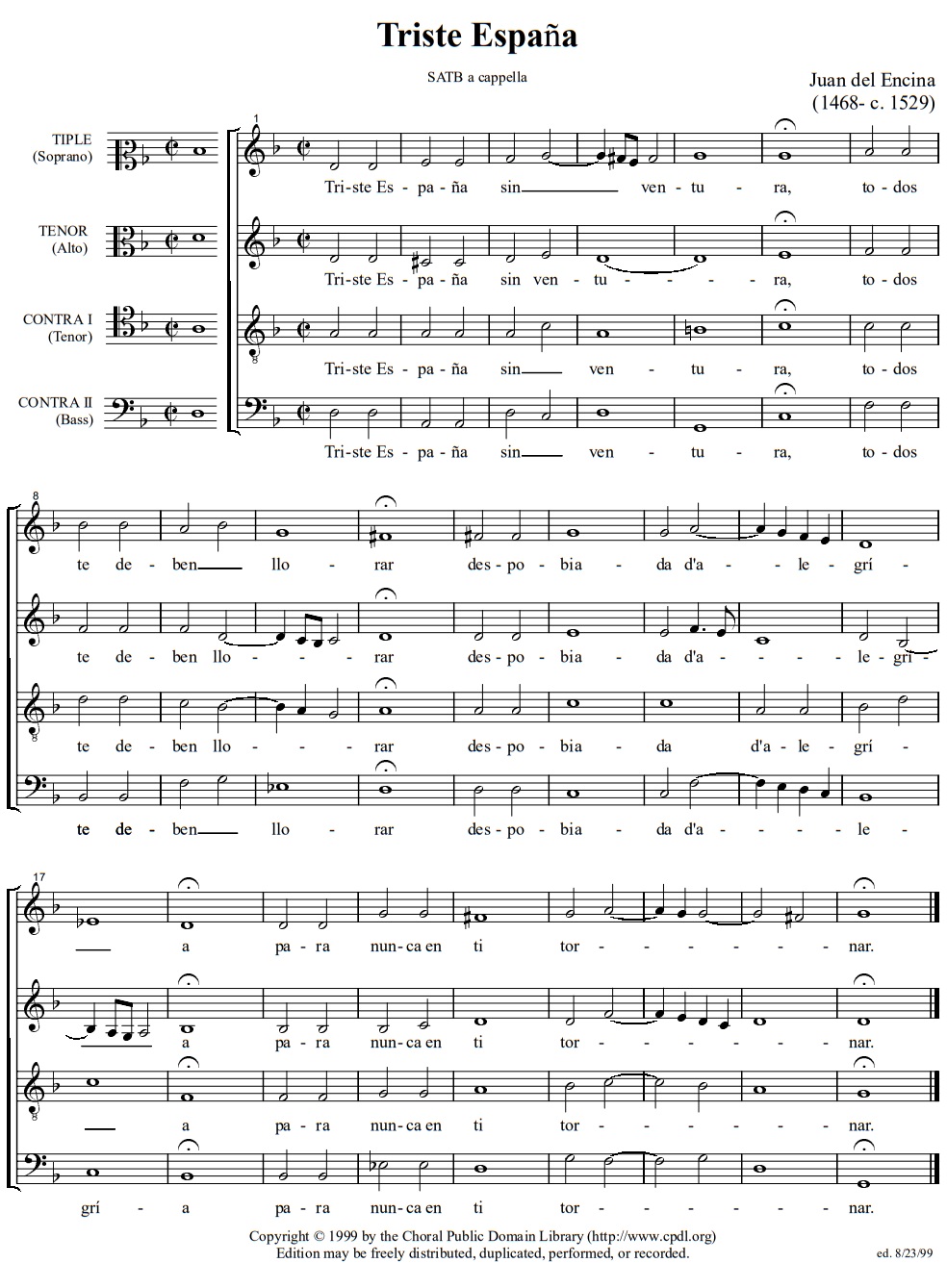

Juan del Encina (12 luglio 1468 - 1529): Triste España sin ventura, romance a 4 voci (1497), dal Cancionero de Palacio (n. 317). La Capella Reial de Catalunya e Hespèrion XXI, dir. Jordi Savall.

Triste España sin ventura,

todos te deven llorar.

Despoblada de alegría,

para nunca en ti tornar.

Tormentos, penas, dolores,

te vinieron a poblar.

Sembróte Dios de plazer

porque naciesse pesar.

Hízote la más dichosa

para más te lastimar.

Tus vitorias y triunfos

ya se hovieron de pagar.

Pues que tal pérdida pierdes,

dime en qué podrás ganar.

Pierdes la luz de tu gloria

y el gozo de tu gozar.

Pierdes toda tu esperança,

no te queda qué esperar.

Pierdes Príncipe tan alto,

hijo de reyes sin par.

Llora, llora, pues perdiste

quien te havía de ensalçar.

En su tierna juventud

te lo quiso Dios llevar.

Llevóte todo tu bien,

dexóte su desear,

porque mueras, porque penes,

sin dar fin a tu penar.

De tan penosa tristura

no te esperes consolar.

An appealing instrumental rendition by The Musicians of Swanne Alley.

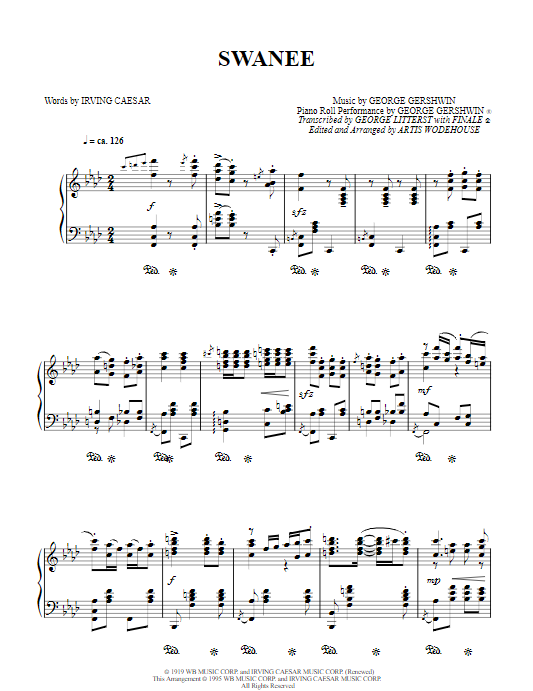

George Gershwin (1898 - 11 luglio 1937): Swanee (1919) eseguito al pianoforte dall’autore (incisione su rullo per pianoforte automatico). Il brano fu concepito, almeno in parte, come parodia di Old Folks At Home ovvero Swanee River (1851), famosissimo minstrel song di Stephen Foster.

Lo stesso brano cantato da Al Jolson, sul testo originale di Irving Caesar, nel film Rapsodia in blu (Rhapsody in Blue), biografia cinematografica di Gershwin diretta nel 1945 da Irving Rapper.

I’ve been away from you a long time.

I never thought I’d missed you so.

Somehow I feel

You love is real,

Near you I long to wanna be.

The birds are singin’, it is song time,

The banjos strummin’ soft and low.

I know that you

Yearn for me too.

Swanee! You’re calling me!

Swanee!

How I love you, how I love you!

My dear ol’ Swanee,

I’d give the world to be

Among the folks in

D-I-X-I-E-ven now My mammy’s

Waiting for me,

Praying for me,

Down by the Swanee.

The folks up north will see me no more

When I go to the Swanee Shore!

Swanee eseguito dal Banjo-Orchestra, uno strumento meccanico recentemente prodotto dalla D. C. Ramey Piano Company di Marysville, Ohio, sulla base del pressoché omonimo Banjorchestra, realizzato nel 1914 dalla Connorized Music Company, che aveva sedi a New York, a Chicago e a Saint Louis.

José de Nebra (1702 - 11 luglio 1768): Salve regina per 2 cori a 8 voci, 2 violini e basso continuo. Ensemble Los Elementos.

Ivresse de jeunesse

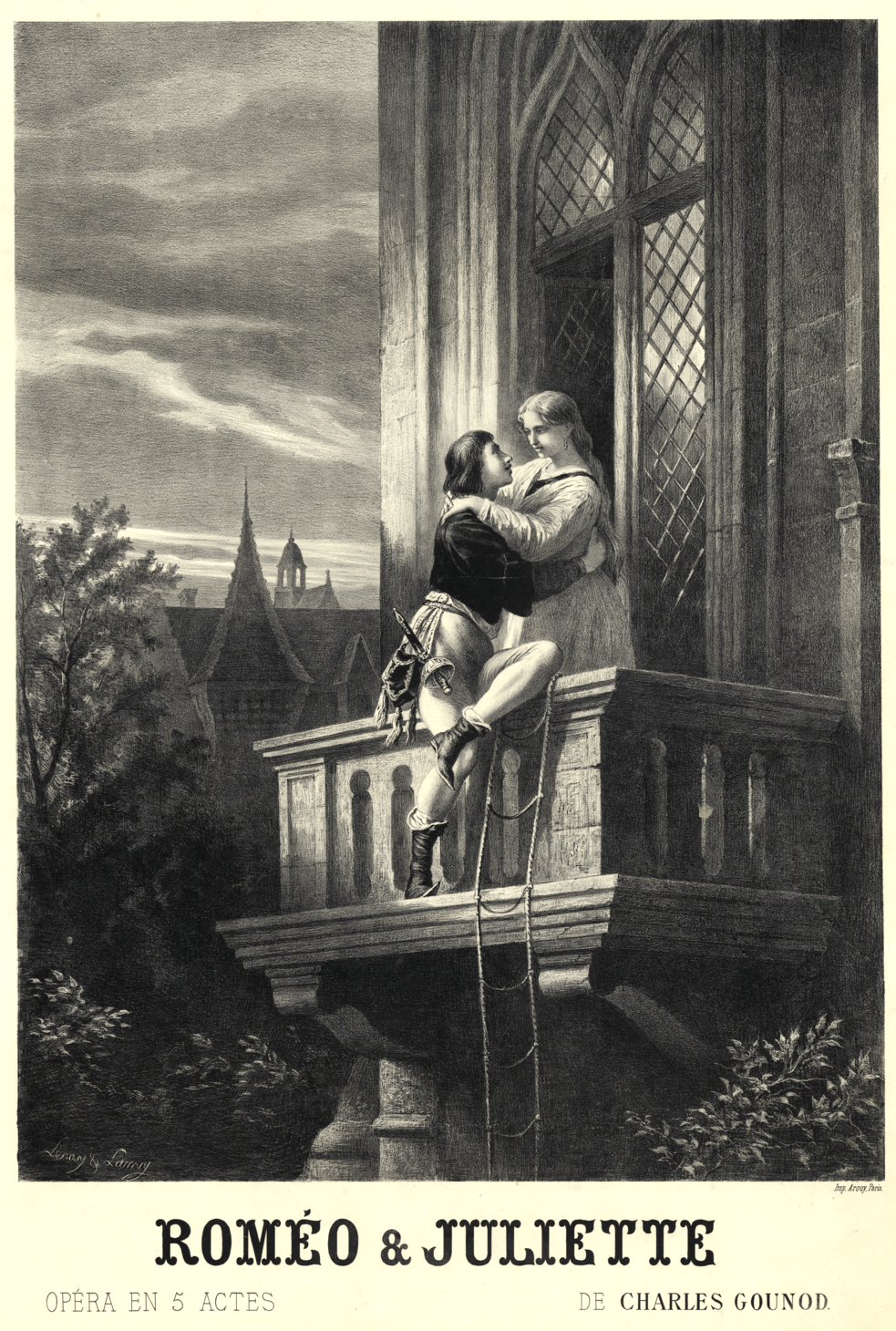

Charles Gounod (1818 - 1893): «Je veux vivre», Juliette’s valse-ariette (waltz song) from the 1st act of the opera Roméo et Juliette (1867), libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Natalie Dessay, soprano; Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse conducted by Michel Plasson.

Ah!

Je veux vivre

Dans ce rêve qui m’enivre

Ce jour encore!

Douce flamme,

Je te garde dans mon âme

Comme un trésor!

Cette ivresse de jeunesse

Ne dure, hélas, qu’un jour!

Puis vient l’heure

Où l’on pleure,

Le cœur cède à l’amour

Et le bonheur fuit sans retour!

Loin de l’hiver morose

Laisse-moi sommeiller

Et respirer la rose

Avant de l’effeuiller.

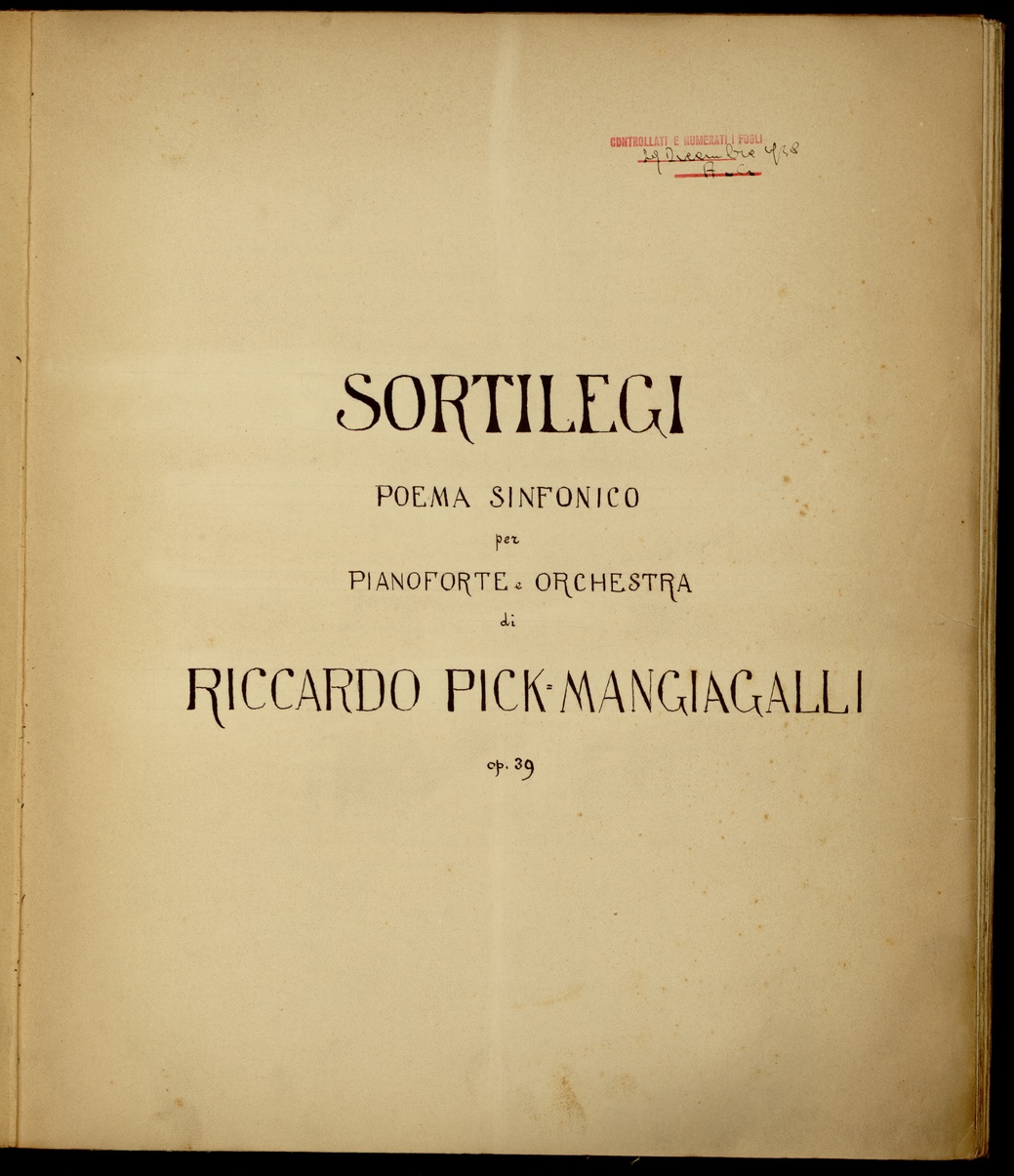

Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli (10 luglio 1882 - 8 luglio 1949): Sortilegi, poema sinfonico per pianoforte e orchestra op. 39 (1917). Stephanie Onggowinoto, pianoforte; Jakarta Concert Orchestra, dir. Avip Priatna.

Sigismund von Neukomm (10 luglio 1778 - 1858): Sinfonie héroïque in re maggiore op. 19 (1818). Kölner Akademie, dir. Michael Alexander Willens.

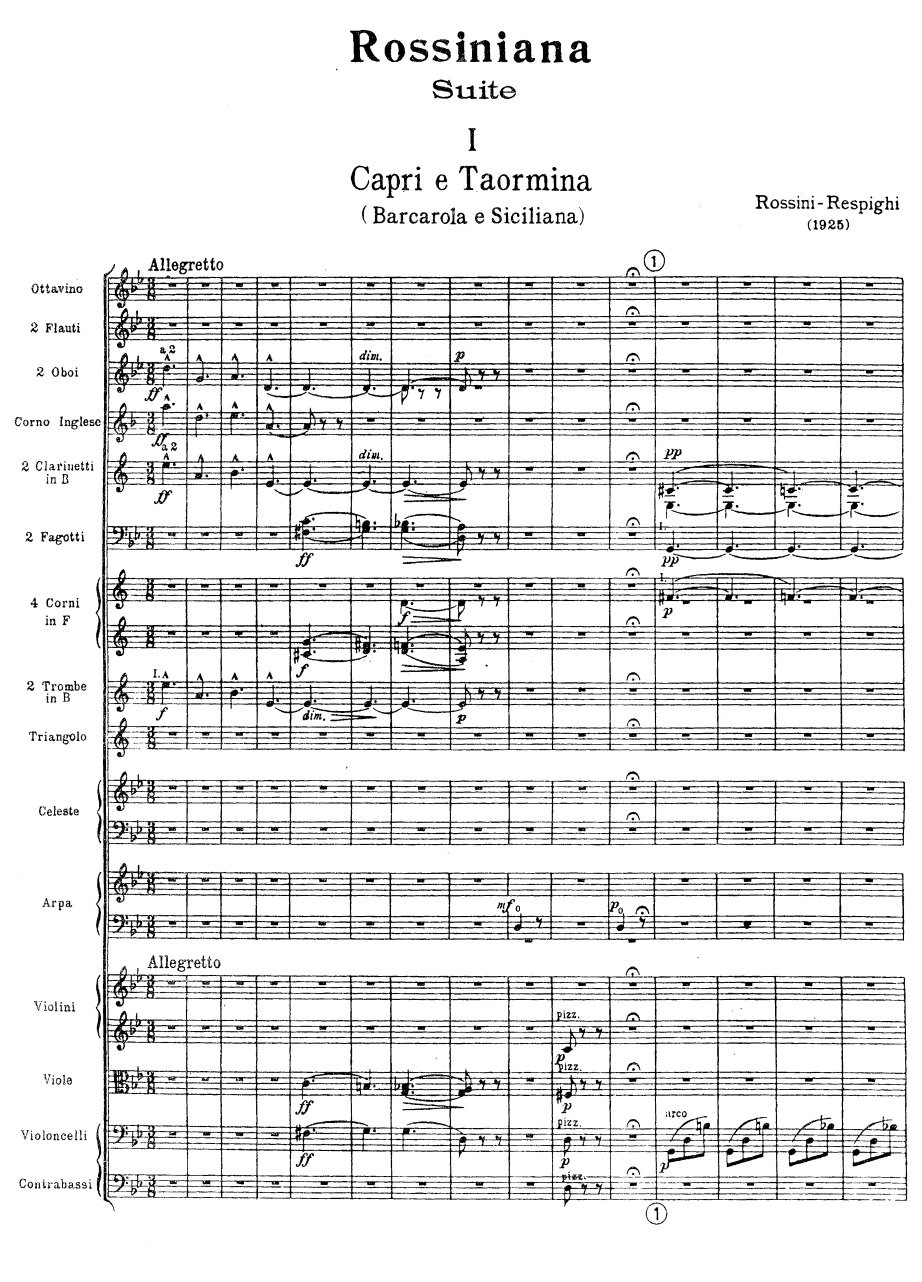

Ottorino Respighi (9 luglio 1879 - 1936): Rossiniana, suite sinfonica (1925) su temi di Gioachino Rossini (tratti da Quelques rien pour album per pianoforte). Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, dir. Ernest Ansermet.

Oliver Knussen (1952 - 9 luglio 2018): Sinfonia n. 3 op. 18 (1973-79). Philharmonia Orchestra, dir. Michael Tilson Thomas.

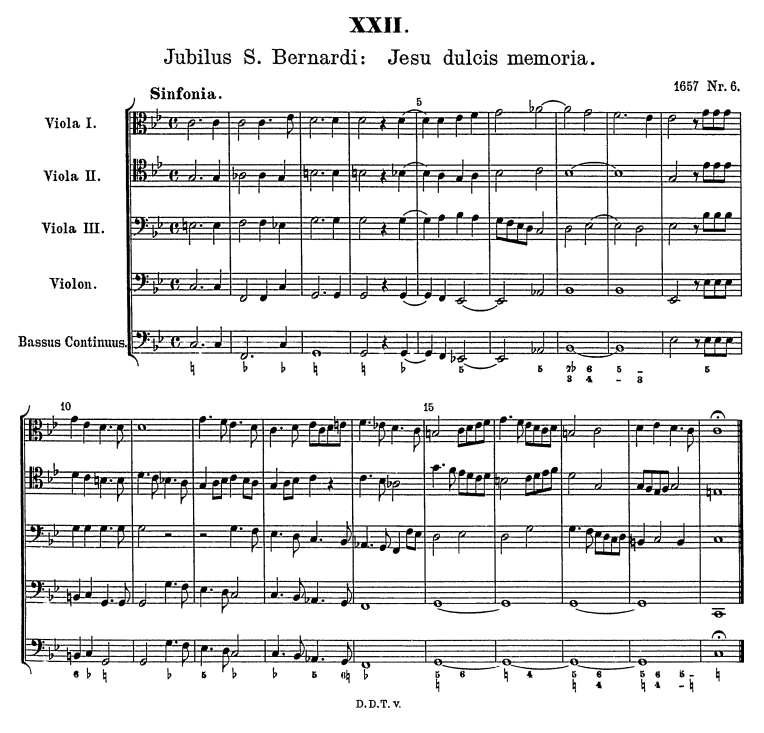

Johann Rudolf Ahle (1625 - 9 luglio 1673): Jesu dulcis memoria, mottetto per voce, 3 viole, violone e basso continuo (1657). Henri Ledroit, haute-contre; Ricercar Consort.

Jesu dulcis memoria,

dans vera cordi gaudia,

et super mel et omnia

eius dulcis praesentia.

Nil canitur suavius,

nil auditur iocundius,

nil cogitatur dulcius

quam Jesus Dei filius.

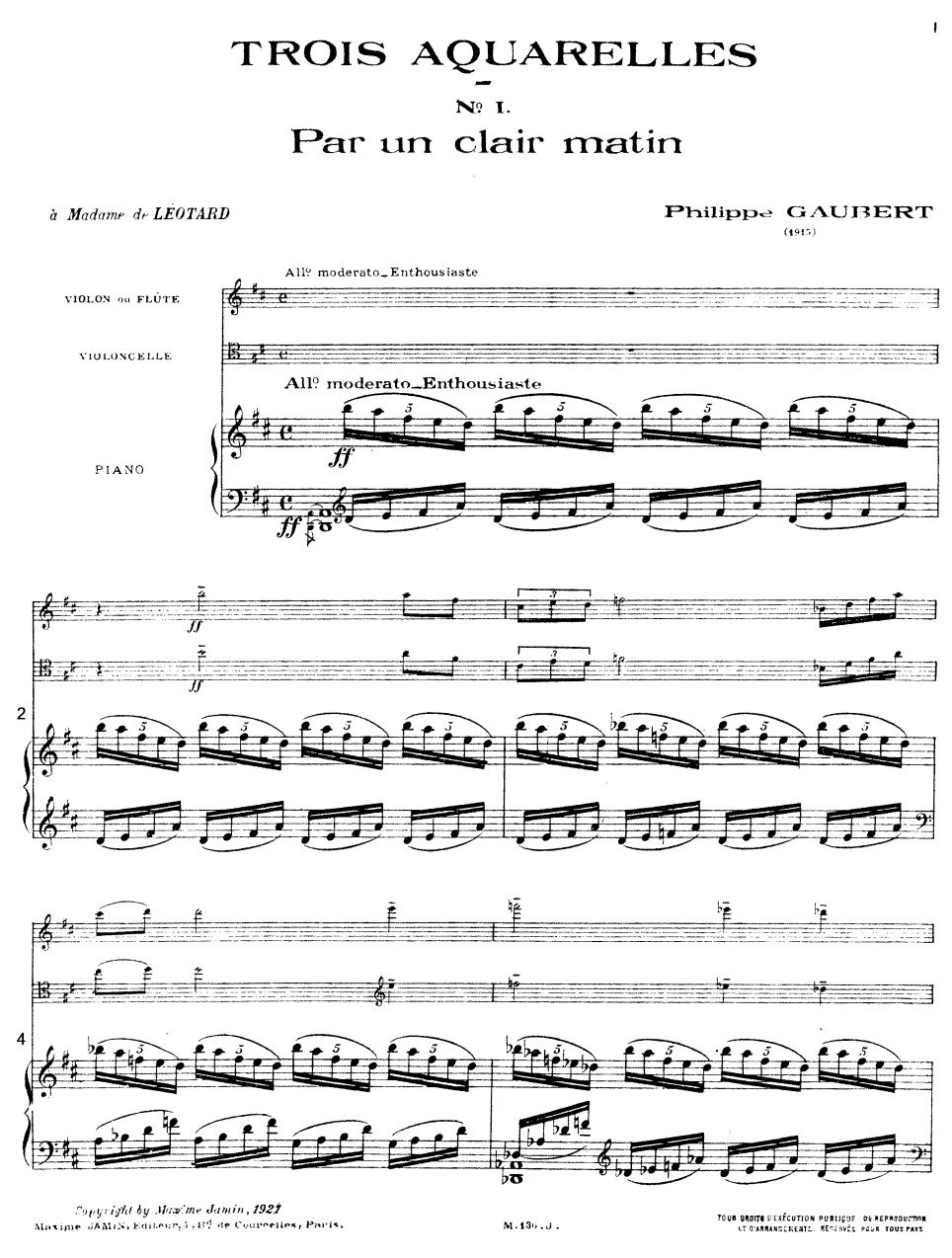

Philippe Gaubert (5 luglio 1879 - 8 luglio 1941): Trois Aquarelles per flauto, violoncello e pianoforte (1921). Leone Buyse, flauto; Desmond Hoebig, violoncello; Robert Moeling, pianoforte.

Hanspeter Kyburz (8 luglio 1960): Maelstrom per orchestra (1998). SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, dir. Hans Zender.

Percy Grainger (8 luglio 1882 - 1961): In a Nutshell, «Suite for Orchestra, Piano and Deagan Percussion Instruments» (1916). BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, dir. Richard Hickox.

Ophelia sings

Anonymous (16th century): How should I your true love know, song of Ophelia from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, act 4, scene 5. Alfred Deller, countertenor; Desmond Dupré, lute.

How should I your true-love know

From another one?

By his cockle bat and staff

And his sandal shoon.

He is dead and gone, lady,

He is dead and gone;

At his head a grass-green turf,

At his heels a stone.

White his shroud as the mountain snow,

Larded with sweet flowers.

Which bewept to the grave did go

With true-love showers.