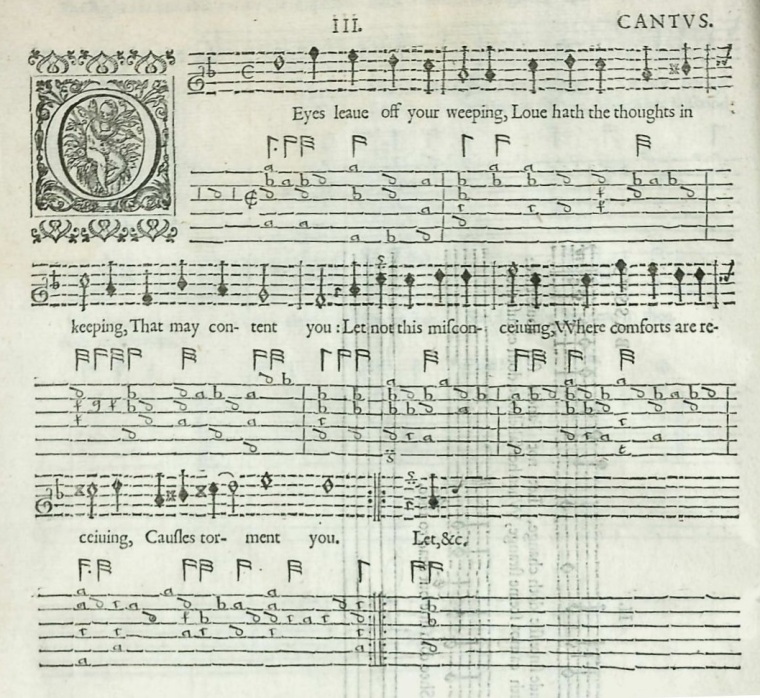

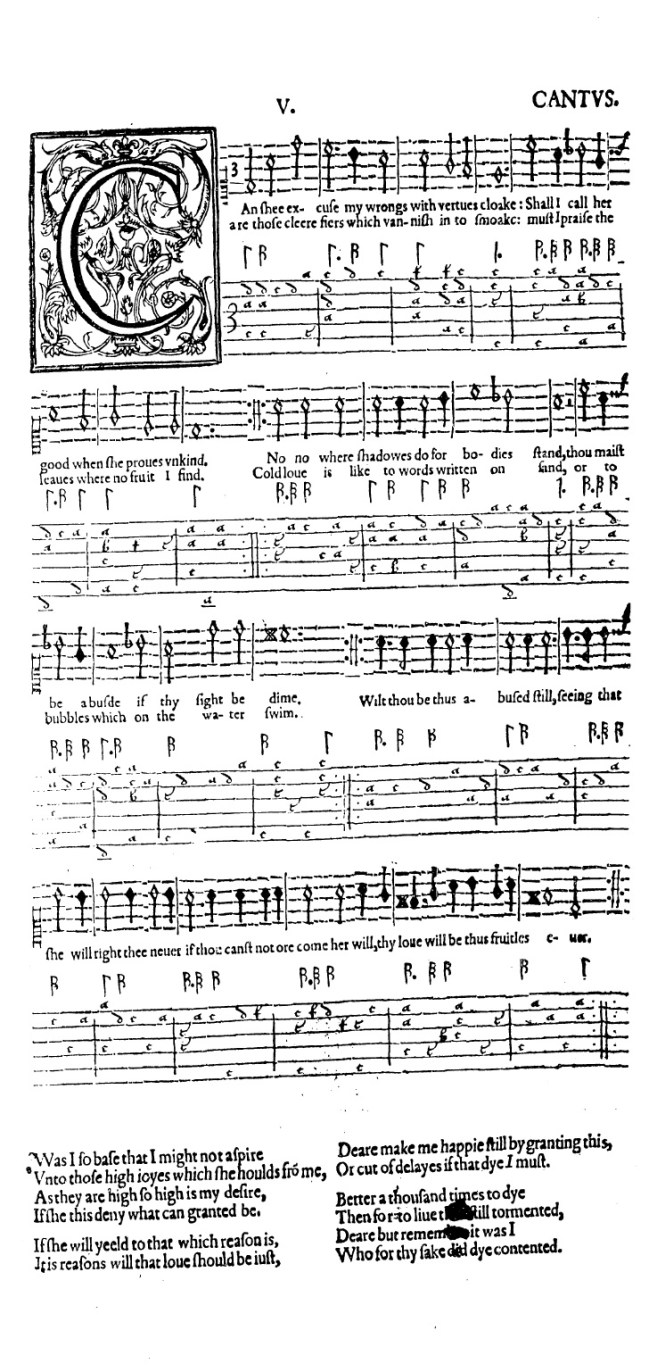

John Dowland (1563 - 1626): Can she excuse my wrongs, ayre, dal First Booke of Songes or Ayres (1597). Emma Kirkby, soprano; Anthony Rooley, liuto.

Can she excuse my wrongs with Virtue’s cloak?

Shall I call her good when she proves unkind?

Are those clear fires which vanish into smoke?

Must I praise the leaves where no fruit I find?

No, no; where shadows do for bodies stand,

That may’st be abus’d if thy sight be dim.

Cold love is like to words written on sand,

Or to bubbles which on the water swim.

Wilt thou be thus abused still,

Seeing that she will right thee never?

If thou canst not o’ercome her will,

Thy love will be thus fruitless ever.

Was I so base, that I might not aspire

Unto those high joys which she holds from me?

As they are high, so high is my desire,

If she this deny, what can granted be?

If she will yield to that which reason is,

It is reason’s will that love should be just.

Dear, make me happy still by granting this,

Or cut off delays if that I die must.

Better a thousand times to die

Than for to live thus still tormented:

Dear, but remember it was I

Who for thy sake did die contented.

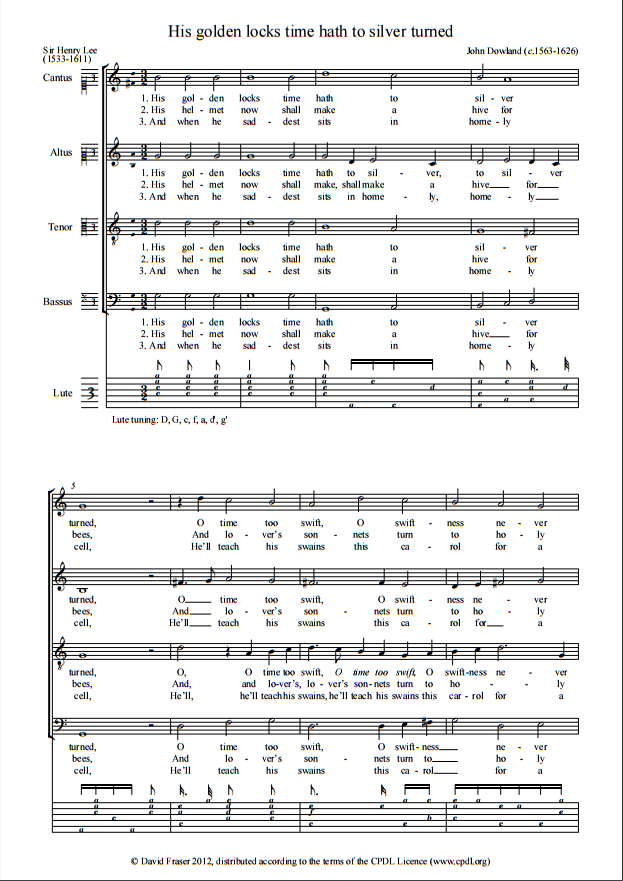

Il testo – adattato a un tema di gagliarda: in qualche fonte, la versione strumentale del brano (qui) reca il titolo The Earl of Essex [ his ] Galliard – fa forse riferimento alle vicende di Robert Devereux, 2° conte di Essex (1566-1601), che potrebbe essere l’autore dei versi. È probabile che sia da collegarsi a Robert Devereux la citazione della melodia tradizionale The woods so wild, da Dowland inserita nel terzo periodo, affidata a una voce intermedia (tenore; testo: Wilt thou be thus abused still ecc.): farebbe riferimento al fatto che il conte di Essex soleva ritirarsi in una casa di sua proprietà, sita nei boschi a nord-est di Londra.

The woods so wild è un ballad assai diffuso in epoca Tudor: pare che fosse particolarmente caro a Enrico VIII. Variazioni sulla melodia si devono a William Byrd (riportate dal Fitzwilliam Virginal Book e dal My Lady Nevell’s Book) e a Orlando Gibbons.

William Byrd (c1540 - 1623): The Woods so Wilde, variazioni. Michael Maxwell Steer, clavicembalo.

Orlando Gibbons (1583 - 1625): The Woods so Wild, variazioni. Michael Maxwell Steer, clavicembalo.

Un’altra interpretazione del brano di Dowland, ove la parte che comprende la citazione della melodia tradizionale è eseguita con un flauto dolce. Karin Gyllenhammar, soprano; Mirjam-Luise Münzel, flauto; David Leeuwarden, liuto; Alina Rotaru, clavicembalo.

English translation: please

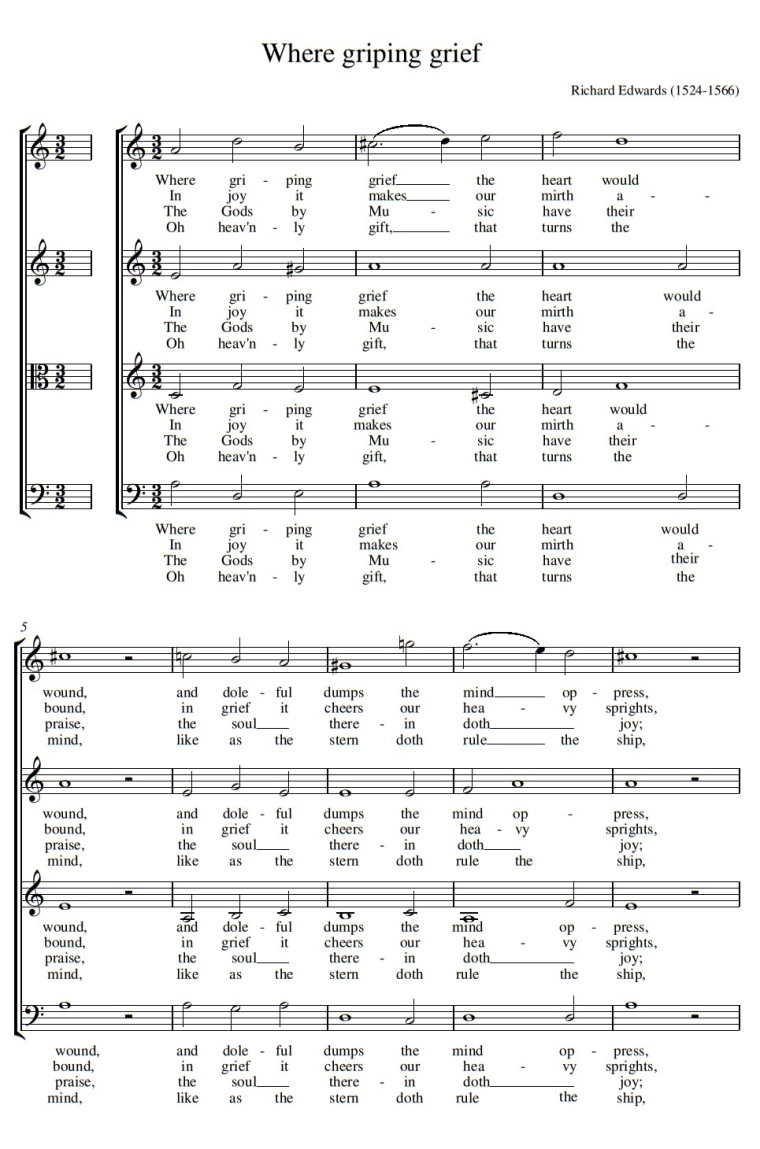

English translation: please  Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

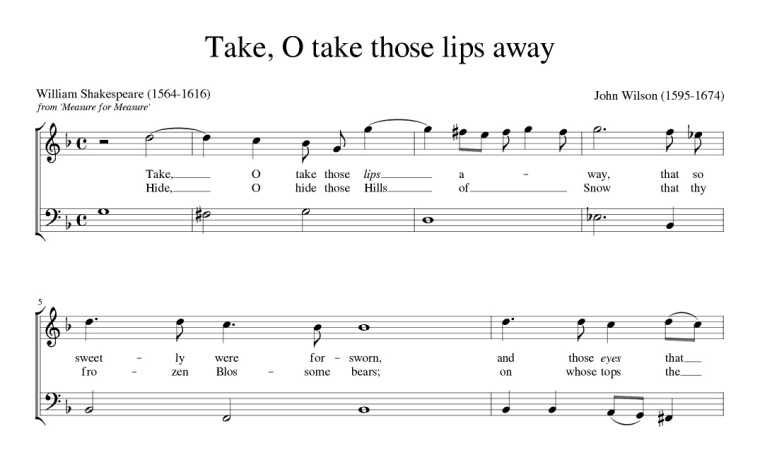

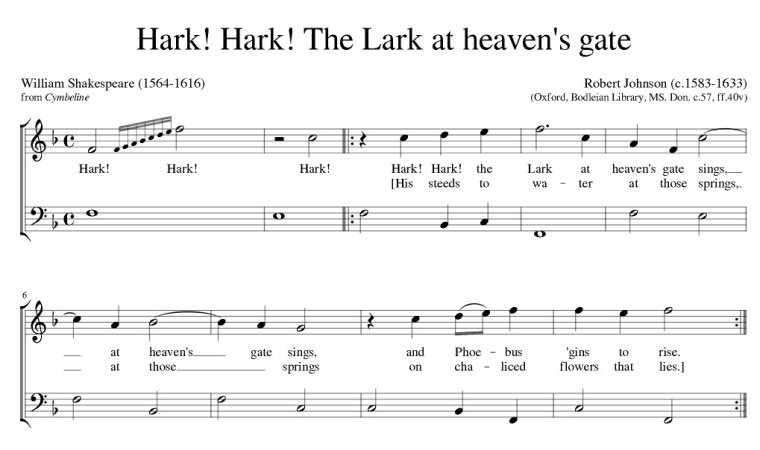

La prima strofa si trova nella commedia di Shakespeare Misura per misura (atto IV, scena 1a), rappresentata per la prima volta nel 1604; non sappiamo su quale melodia fosse cantata. Prima e seconda strofa sono nel dramma Rollo Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother, scritto in collaborazione da John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson e George Chapman in data imprecisabile (comunque non prima del 1612). Non è dato di sapere se la seconda strofe sia un’aggiunta di Fletcher oppure se tanto Shakespeare quanto Fletcher si siano rifatti a una canzone popolare in voga ai loro tempi.

La prima strofa si trova nella commedia di Shakespeare Misura per misura (atto IV, scena 1a), rappresentata per la prima volta nel 1604; non sappiamo su quale melodia fosse cantata. Prima e seconda strofa sono nel dramma Rollo Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother, scritto in collaborazione da John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson e George Chapman in data imprecisabile (comunque non prima del 1612). Non è dato di sapere se la seconda strofe sia un’aggiunta di Fletcher oppure se tanto Shakespeare quanto Fletcher si siano rifatti a una canzone popolare in voga ai loro tempi.