I singoli movimenti della Sinfonia sono ispirati da altrettanti componimenti poetici di autori diversi, fra i quali lo stesso Godard; le poesie sono riportate sulla partitura nella forma qui sotto indicata.

I. Les Éléphants (Leconte de Lisle): Andante con moto

Le sable rouge est comme une mer sans limite,

Et qui flambe, muette, affaissée en son lit.

Une ondulation immobile remplit

L’horizon aux vapeurs de cuivre où l’homme habite.

[…]

Tel l’espace enflammé brûle sous les cieux clairs;

Mais, tandis que tout dort aux mornes solitudes,

Les éléphants rugueux, voyageurs lents et rudes,

Vont au pays natal à travers les déserts.

D’un point de l’horizon, comme des masses brunes,

Ils viennent, soulevant la poussière et l’on voit,

Pour ne point dévier du chemin le plus droit,

Sous leur pied large et sûr crouler au loin les dunes.

[…]

L’oreille en éventail, la trompe entre les dents,

Ils cheminent, l’œil clos. Leur ventre bat et fume,

Et leur sueur dans l’air embrasé monte en brume,

Et bourdonnent autour mille insectes ardents.

Mais qu’importent la soif et la mouche vorace,

Et le soleil cuisant leur dos noir et plissé?

Ils révent en marchant du pays délaissé,

Des forêts de figuiers où s’abrita leur race.

Ils reverront le fleuve échappé des grands monts,

Où nage en mugissant l’hippopotame énorme;

Où, blanchis par la lune, et projetant leur forme,

Ils descendaient pour boire en écrasant les joncs.

Aussi, pleins de courage et de lenteur ils passent

Comme une ligne noire, au sable illimité;

Et le désert reprend son immobilité

Quand les lourds voyageurs à l’horizon s’effacent.

II. Chinoiserie (Auguste de Châtillon): Allegro moderato [5:35]

On entendait, au lointain,

Tinter un son argentin

De triangles, de sonnettes,

De tambourins, de clochettes;

C’étaient des gens de Nankin,

Des Mandarins en goguette,

Qui revenaient d’une fête,

D’une fête de Pékin.

III. Sara la Baigneuse (Victor Hugo): Andantino con moto [9:22]

Sara, belle d’indolence,

Se balance

Dans un hamac, au-dessus

Du bassin d’une fontaine

Toute pleine

D’eau puisée à l’Ilyssus;

Et la frêle escarpolette

Se reflète

Dans le transparent miroir,

Avec la baigneuse blanche

Qui se penche,

Qui se penche pour se voir.

[…]

Mais Sara la nonchalante

Est bien lente

A finir ses doux ébats;

Toujours elle se balance

En silence,

Et va murmurant tout bas:

“Oh ! si j’étais capitane,

“Ou sultane,

“Je prendrais des bains ambrés,

“Dans un bain de marbre jaune,

“Prés d’un trône,

“Entre deux griffons dorés !

“J’aurais le hamac de soie

“Qui se ploie

“Sous le corps prêt à pâmer;

“J’aurais la molle ottomane

“Dont émane

“Un parfum qui fait aimer.”

[…]

Ainsi se parle en princesse,

Et sans cesse

Se balance avec amour,

La jeune fille rieuse,

Oublieuse

Des promptes ailes du jour.

[…]

IV. Le rêve de la Nikia (Benjamin Godard): Quasi adagio [15:36]

Elle est jeune, elle est belle; et pourtant la tristesse

Assombrit ses grands yeux.

Aucun penser d’amour ne charme sa jeunesse.

Son cœur ambitieux

Rêve d’une contrée, inconue et lointaine,

Où d’un peuple puissant

Et respecté de tous, elle deviendrait reine.

Là-bas, à l’Occident,

Sont de grandes cités aux splendeurs sans pareilles;

Là, la Science et l’Art,

Au souffle du Génie, enfantent des merveilles!…

Son beau rêve, au hasard,

Vers ces mondes nouveaux, l’emporte sur son aile.

Son cœur ambitieux

N’a nul penser d’amour. Elle est jeune, elle est belle,

Et pourtant la tristesse assombrit ses grands yeux.

V. Marche turque (Godard): Tempo di marcia [21:55]

Là – Allah – Ellalah!

Que les chrétiens maudits périssent sous la hache

Et que Mahomet règne! Il n’est point de cœur lâche

Parmi les fiers soldats du Prophète sacré.

Que dans tout l’Univers Allah soit adoré!

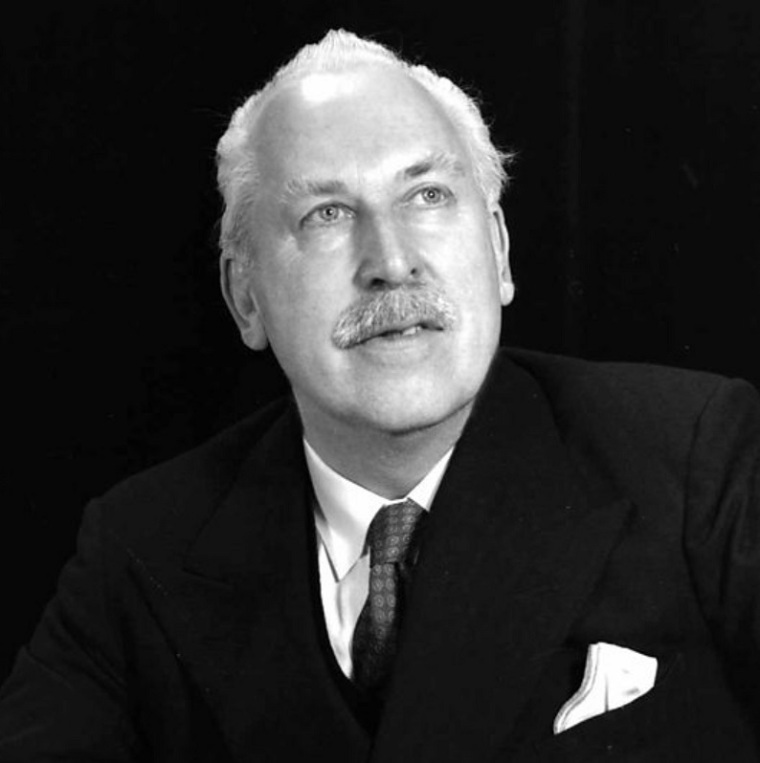

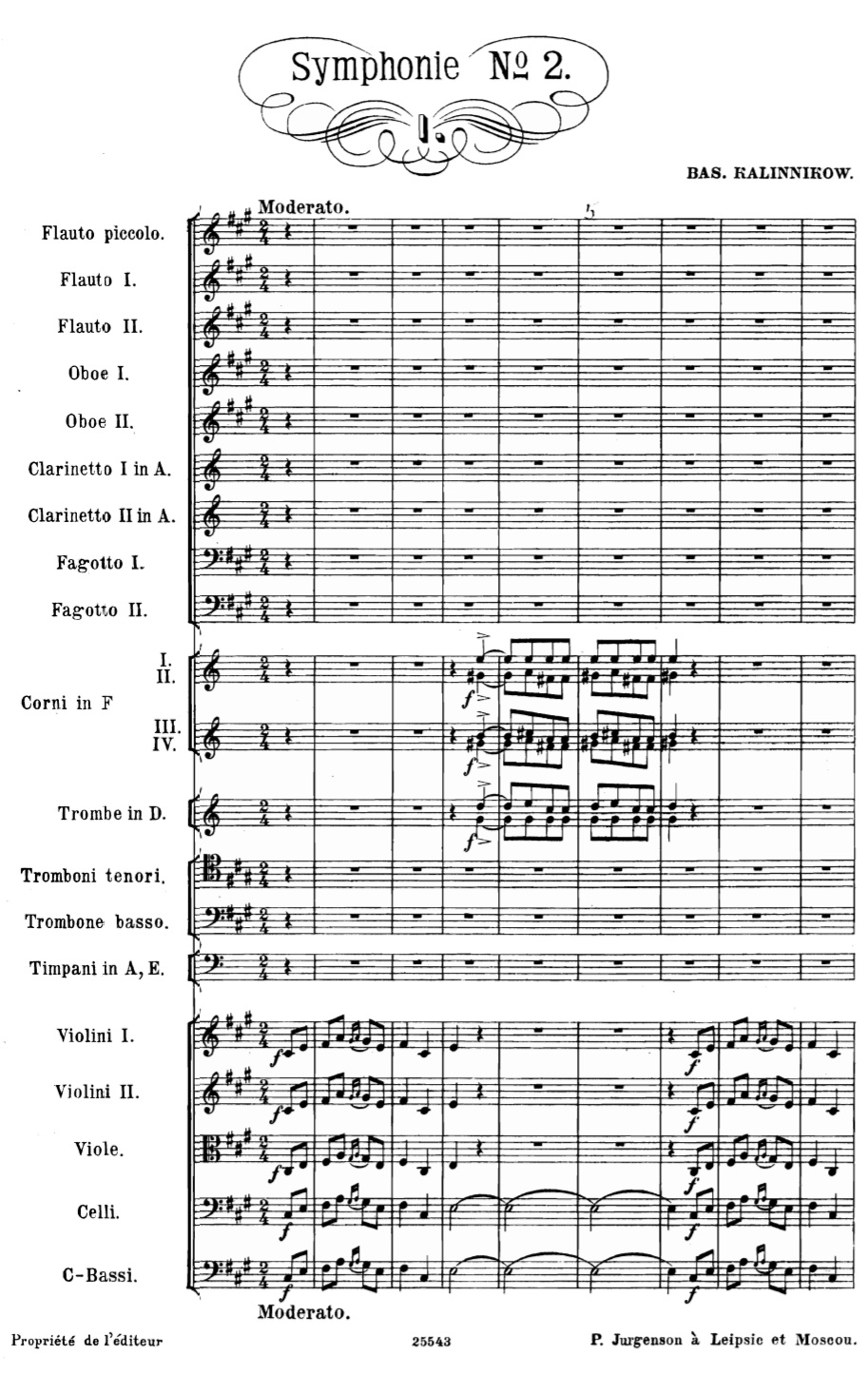

Vasilij Sergeevič Kalinnikov (13 gennaio 1866 - 1901): Sinfonia n. 2 in la maggiore (1897). Scottish National Orchestra, dir. Neeme Järvi.

Vasilij Sergeevič Kalinnikov (13 gennaio 1866 - 1901): Sinfonia n. 2 in la maggiore (1897). Scottish National Orchestra, dir. Neeme Järvi.

Joly Braga Santos (14 maggio 1924 - 1988): Três Esboços sinfónicos op. 38 (1961). Royal Scottish National Orchestra, dir. Álvaro Cassuto.

Joly Braga Santos (14 maggio 1924 - 1988): Três Esboços sinfónicos op. 38 (1961). Royal Scottish National Orchestra, dir. Álvaro Cassuto.