P.D.Q. Bach (Peter Schickele, 1935 - 16 gennaio 2024): Concerto for Simply Grand Piano and Orchestra. Jeffrey Biegel, pianoforte; Philharmonia Northwest, dir. Julia Tai.

P.D.Q. Bach (Peter Schickele, 1935 - 16 gennaio 2024): Concerto for Simply Grand Piano and Orchestra. Jeffrey Biegel, pianoforte; Philharmonia Northwest, dir. Julia Tai.

Peter Schickele (1935 - 16 gennaio 2024): Last Tango in Bayreuth per 4 fagotti (1974). Tennessee Bassoon Quartet.

Amene divagazioni sul Tristanakkord 🙂

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750): «Flösst, mein Heiland, flösst dein Namen», aria per soprano, oboe e organo, dalla IV parte del Weihnachtsoratorium BWV 248 (1734). Nancy Argenta, soprano; The English Baroque Soloists, dir. John Eliot Gardiner.

Testo di Christian Friedrich Henrici alias Picander:

|

Flößt, mein Heiland, flößt dein Namen Auch den allerkleinsten Samen Jenes strengen Schreckens ein? Nein, du sagst ja selber nein. (Echo: Nein! ) Sollt ich nun das Sterben scheuen? Nein, dein süßes Wort ist da! Oder sollt ich mich erfreuen? Ja, du Heiland sprichst selbst ja. (Echo: Ja! ) |

Potrà il tuo nome, Redentore, infondere anche il più piccolo seme di quel tremendo terrore? No, tu stesso dici no. (Eco : No!) Dovrei dunque temere la morte? No, la dolce tua parola è qui. Oppure dovrei rallegrarmi? Sì, Redentore, tu stesso dici sì. (Eco : Sì!) |

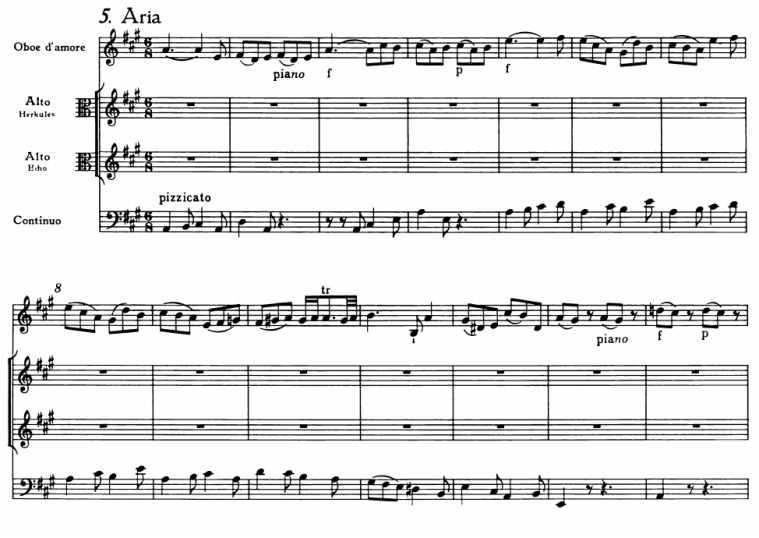

«Flösst, mein Heiland» è una parodia dell’aria «Treues Echo dieser Orten» per contralto, oboe d’amore e orchestra, quinto brano della cantata profana Lasst uns sorgen, lasst uns wachen (Die Wahl des Herkules) BWV 213, composta l’anno precedente (1733) per l’undicesimo compleanno del principe elettore Federico Cristiano di Sassonia (1722 - 1763):

Carolyn Watkinson, contralto; Kammerorchester Berlin, dir. Peter Schreier.

Testo dello stesso Picander:

| Treues Echo dieser Orten, Sollt ich bei den Schmeichelworten Süßer Leitung irrig sein? Gib mir deine Antwort: Nein! (Echo: Nein! ) Oder sollte das Ermahnen, Das so mancher Arbeit nah, Mir die Wege besser bahnen? Ach! so sage lieber: Ja! (Echo: Ja! ) |

Eco fedele di questi luoghi, dovrò da parole adulatrici essere indotto in errore? Dammi la tua risposta: No! (Eco : No!) Oppure sarà l’esortazione che prelude a così tanta fatica a indicarmi correttamente la via? Oh! Allora dimmi piuttosto: Sì! (Eco : Sì!) |

Anonimo: J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre, chanson tradizionale francese (versione borgognona). Le Poème Harmonique, dir. Vincent Dumestre.

Le origini di questa chanson, una parodia del Dies irae, risalgono probabilmente al Quattrocento.

C’est dans neuf ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

C’est dans neuf ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

C’est dans huit ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

C’est dans huit ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

C’est dans sept ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler,

C’est dans sept ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rebeuillés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard cheuler.

C’est dans six ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans six ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans cinq ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans cinq ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans quatre ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans quatre ans je m’en irai,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai rechignés,

J’ai ouï le loup, le renard chanter.

C’est dans trois ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

C’est dans trois ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

C’est dans deux ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

C’est dans deux ans je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

C’est dans un an je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

C’est dans un an je m’en irai,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lièvre,

C’est moi-même qui les ai revirés,

J’ai vu le loup, le renard danser.

Una notte di cinque anni fa, mentre salivamo il sentiero che passa vicino a casa per l’ultima passeggiata prima di andare a nanna, Puck e io vedemmo il lupo. Era un grosso lupo nero che viveva da solo nei boschi là intorno; l’avevamo già incontrato in altre occasioni negli anni precedenti, ma mai eravamo stati così vicini. Poco prima della sua comparsa Puck si era irrigidito fiutando l’aria e fissando un punto dove il sentiero passa fra vecchie case disabitate: da lì pochi istanti dopo arrivò di gran carriera il lupo. Puck fu molto coraggioso: prima che io potessi fare un gesto qualsiasi l’aveva già messo in fuga. Per fortuna, nessuno si è fatto male.

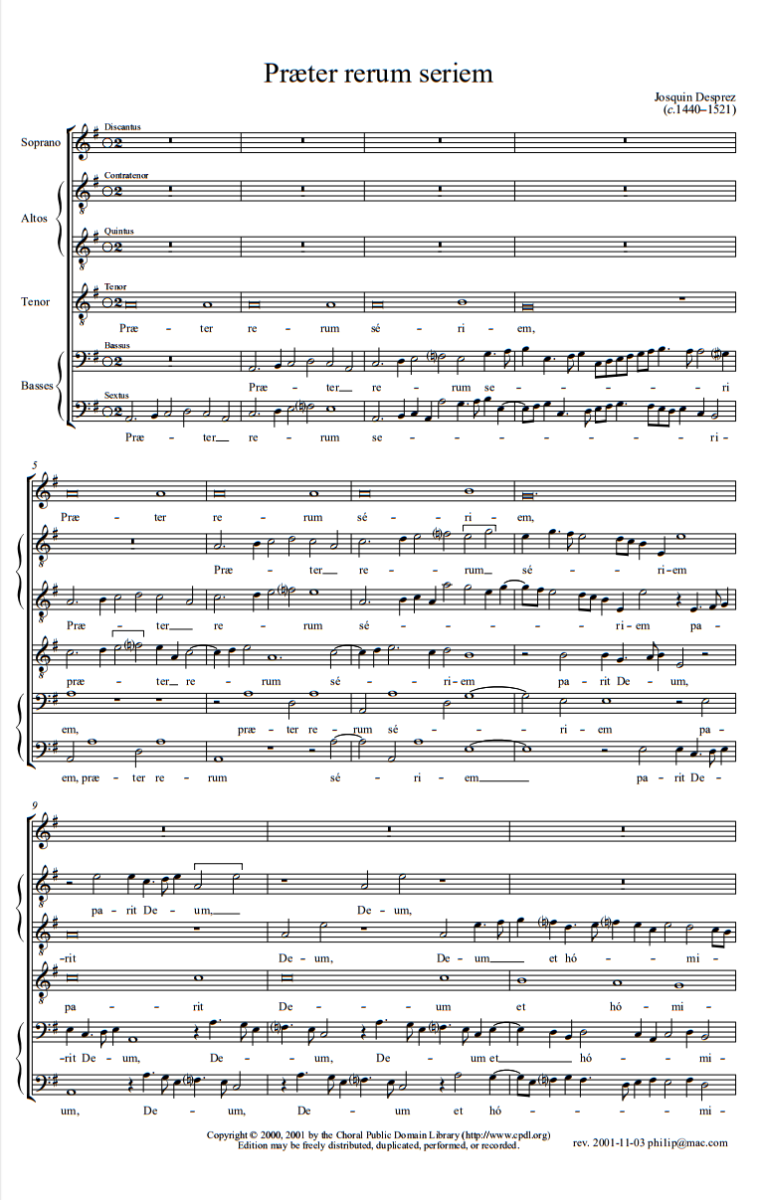

Josquin des Prez (c1450 - 1521): Praeter rerum seriem, mottetto a 6 voci (pubblicato in Motetti de la corona, Libro III, 1519). Lumina Ensemble, dir. Anna Pope.

Præter rerum seriem

parit Deum hominem

virgo mater.

Nec vir tangit virginem

nec prolis originem

novit pater.

Virtus Sancti Spiritus

opus illud cœlitus

operatur.

Initus et exitus

partus tui penitus

quis scrutatur?

Dei providentia

quæ disponit omnia

tam suave.

Tua puerperia

transfer in mysteria.

Mater ave.

Sethus Calvisius (Seth Kalwitz; 1556 - 1615): Praeter rerum seriem, mottetto a 6 voci, parode ad Josquini (pubblicato in Florilegium selectissimarum cantionum, 1603, n. 85). Kaleidos Ensemble.

Praeter rerum seriem

Parit Deum et hominem

Virgo mater.

Nec vir tangit virginem,

Nec prolis originem

Novit pater.

Virtus Sancti Spiritus

Opus illud caelitus

Operatur.

Initus et exitus

Partus tui penitus

Quis scrutatur?

Dei providentia

Haec disponit omnia

Tam suave,

Et pios caelestia

Transfert in mysteria.

Puer ave.

Con il suo ensemble, The Broadside Band, Jeremy Barlow ha lavorato a lungo e proficuamente sulle musiche utilizzate da Johann Christoph Pepusch nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728) di John Gay: la quale è l’unica ballad opera di cui si parli ancora ai nostri giorni, grazie anche al rifacimento brechtiano del 1928, Die Dreigroschenoper, che adotta però musiche originali composte da Kurt Weill. Per l’Opera del mendicante invece, com’è noto, Pepusch adattò i testi di Gay a melodie che all’epoca avevano una certa notorietà, prendendole a prestito da broadside ballads, arie d’opera, inni religiosi e canti di tradizione popolare.

Oltre a produrre un’edizione completa del lavoro di Gay e Pepusch, Barlow e la sua band hanno inciso (per Harmonia Mundi, 1982) anche un’antologia degli airs più famosi (in tutto nove brani), di ciascuno dei quali proponendo non solo la versione dell’Opera del mendicante ma anche la composizione originale e eventuali altre sue trasformazioni, varianti e parodie.

L’ultima sezione dell’antologia, che qui sottopongo alla vostra attenzione, è dedicato a Greensleeves. Comprende, nell’ordine:

una improvvisazione sul passamezzo antico, eseguita al liuto da George Weigand

Greensleeves, la più antica versione nota della melodia (dal William Ballet’s Lute Book, c1590-1603) con la più antica versione nota del testo (da A Handful of Pleasant Delights, 1584), cantata da Paul Elliott accompagnato al liuto da Weigand [1:13]

Alas, my love, you do me wrong,

To cast me off discourteously.

And I have loved you so long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my Lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you wouldst crave,

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and goodwill for to have.

Well I will pray to God on high

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me.

Greensleeves, now farewell, adieu,

God I pray to prosper thee,

For I am still thy lover true,

Come once again and love me.

Greensleeves, la versione più diffusa all’inizio del Seicento, secondo William Cobbold (1560 - 1639) e altri autori, con improvvisazioni eseguite da Weigand alla chitarra barocca e da Rosemary Thorndycraft al bass viol [4:07]

la versione dell’Opera del mendicante che già conosciamo, interpretata ancora da Elliott a solo [5:27]

un misto di tre jigs irlandesi eseguito da Barlow al flauto e da Alastair McLachlan al violino [6:03]:

– A Basket of Oysters (da Moore’s Irish Melodies, 1834)

– A Basket of Oysters or Paddythe Weaver (Aird’s selection, 1788)

– Greensleeves (versione raccolta a Limerick nel 1852)

With his ensemble, The Broadside Band, Jeremy Barlow worked extensively and profitably on the music used by Johann Christoph Pepusch in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728): it is the only ballad opera still being talked about in our days, thanks also to Bertolt Brecht’s 1928 remake, Die Dreigroschenoper, which however has original music composed by Kurt Weill. It is not the same for The Beggar’s Opera: Gay’s lyrics were in fact adapted by Pepusch to melodies that at the time already had a certain notoriety, borrowing them from broadside ballads, opera arias, religious hymns and folk songs.

Barlow and his band have recorded a complete edition of Gay and Pepusch’s work, as well as an anthology of its most famous airs (nine pieces in all), of each of which they presented not only The Beggar’s Opera version, but also the original composition and some of its variants and parodies.

The last track of the anthology, the one I submit to your attention here, is dedicated to Greensleeves. It includes, in order:

a lute extemporisation on passamezzo antico ground, performed by George Weigand

Greensleeves, earliest version of melody (from William Ballet’s Lute Book, c1590-1603) with earliest surviving words (A Handful of Pleasant Delights, 1584), sung by Paul Elliott accompanied on lute by Weigand [1:13]

Alas, my love, you do me wrong,

To cast me off discourteously.

And I have loved you so long,

Delighting in your company.

Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves was my heart of gold,

And who but my Lady Greensleeves.

I have been ready at your hand,

To grant whatever you wouldst crave,

I have both waged life and land,

Your love and goodwill for to have.

Well I will pray to God on high

That thou my constancy mayst see,

And that yet once before I die,

Thou wilt vouchsafe to love me.

Greensleeves, now farewell, adieu,

God I pray to prosper thee,

For I am still thy lover true,

Come once again and love me.

Greensleeves, the most widespread version at the beginning of the seventeenth century, according to William Cobbold (1560 - 1639) and other authors, with improvisations performed by Weigand on baroque guitar and by Rosemary Thorndycraft on bass viol [4:07]

The Beggar’s Opera version (we already know it) sung by Elliott a solo [5:27]

a medley of three Irish jigs performed by Barlow on flute and Alastair McLachlan on violin [6:03]:

– A Basket of Oysters (da Moore’s Irish Melodies, 1834)

– A Basket of Oysters or Paddythe Weaver (Aird’s selection, 1788)

– Greensleeves (collected Limerick 1852).

Aleksej Igudesman (22 luglio 1973) « ispirato da Ludwig van Beethoven »: For A Lease per 2 violini (2020). Julian Rachlin e Aleksej Igudesman.

Happy birthday, Aleksej! 🎻🍾🥂 🙂

George Gershwin (1898 - 11 luglio 1937): Swanee (1919) eseguito al pianoforte dall’autore (incisione su rullo per pianoforte automatico). Il brano fu concepito, almeno in parte, come parodia di Old Folks At Home ovvero Swanee River (1851), famosissimo minstrel song di Stephen Foster.

Lo stesso brano cantato da Al Jolson, sul testo originale di Irving Caesar, nel film Rapsodia in blu (Rhapsody in Blue), biografia cinematografica di Gershwin diretta nel 1945 da Irving Rapper.

I’ve been away from you a long time.

I never thought I’d missed you so.

Somehow I feel

You love is real,

Near you I long to wanna be.

The birds are singin’, it is song time,

The banjos strummin’ soft and low.

I know that you

Yearn for me too.

Swanee! You’re calling me!

Swanee!

How I love you, how I love you!

My dear ol’ Swanee,

I’d give the world to be

Among the folks in

D-I-X-I-E-ven now My mammy’s

Waiting for me,

Praying for me,

Down by the Swanee.

The folks up north will see me no more

When I go to the Swanee Shore!

Swanee eseguito dal Banjo-Orchestra, uno strumento meccanico recentemente prodotto dalla D. C. Ramey Piano Company di Marysville, Ohio, sulla base del pressoché omonimo Banjorchestra, realizzato nel 1914 dalla Connorized Music Company, che aveva sedi a New York, a Chicago e a Saint Louis.

What Child is this?, Christmas carol to the tune of Greensleeves (arranged by Marco Frisina), lyrics by William Chatterton Dix (1837 - 1898). Rossella Mirabelli, alto; Choir of the Diocese of Rome conducted by Mgr. Frisina.

What child is this, who, laid to rest,

On Mary’s lap is sleeping,

Whom angels greet with anthems sweet

While shepherds watch are keeping?

This, this is Christ the King,

Whom shepherds guard and angels sing;

Haste, haste to bring Him laud,

The babe, the son of Mary!

Why lies He in such mean estate

Where ox and ass are feeding?

Good Christian, fear: for sinners here

The silent Word is pleading.

Nails, spear shall pierce him through,

The Cross be borne for me, for you;

Hail, hail the Word Made Flesh,

The babe, the son of Mary!

So bring Him incense, gold, and myrrh;

Come, peasant, king, to own Him!

The King of Kings salvation brings;

Let loving hearts enthrone Him!

Raise, raise the song on high!

The virgin sings her lullaby.

Joy! joy! for Christ is born,

The babe, the son of Mary!

What Child is this? è probabilmente il più celebre adattamento spirituale della melodia di Greensleeves. Il testo fa parte del poemetto The Manger Throne, scritto da Dix nel 1865. L’idea dell’adattamento è quasi certamente di John Stainer, organista e compositore britannico (1840 - 1901), e risale al 1871.

What Child is this? è probabilmente il più celebre adattamento spirituale della melodia di Greensleeves. Il testo fa parte del poemetto The Manger Throne, scritto da Dix nel 1865. L’idea dell’adattamento è quasi certamente di John Stainer, organista e compositore britannico (1840 - 1901), e risale al 1871.

What Child is this? is probably the most famous spiritual adaptation of Greensleeves tune. Lyrics is part of the poem The Manger Throne, written by Dix in 1865. The idea of the adaptation is almost certainly by John Stainer, British organist and composer (1840 - 1901), and dates back to 1871.

What Child is this? is probably the most famous spiritual adaptation of Greensleeves tune. Lyrics is part of the poem The Manger Throne, written by Dix in 1865. The idea of the adaptation is almost certainly by John Stainer, British organist and composer (1840 - 1901), and dates back to 1871.

The Beggar’s Opera, Air XXVII: Greensleeves. Roger Daltrey as Macheath.

Since Laws were made for ev’ry Degree,

To curb Vice in others, as well as me,

I wonder we han’t better Company,

Upon Tyburn Tree!

But Gold from Law can take out the Sting;

And if rich Men like us were to swing,

’Twould thin out the Land, such Numbers to string

Upon Tyburn Tree!

Nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728), scritta da John Gay, con musiche tratte perlopiù dal repertorio popolare e adattate da Johann Christoph Pepusch, trova posto anche la melodia di Greensleeves. Il brano è intonato con rabbia e frustrazione da Macheath subito dopo aver appreso di essere stato condannato a morte. Per «Tyburn Tree» si intende la forca: Tyburn era il villaggio del Middlesex in cui si eseguivano le sentenze capitali.

Nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728), scritta da John Gay, con musiche tratte perlopiù dal repertorio popolare e adattate da Johann Christoph Pepusch, trova posto anche la melodia di Greensleeves. Il brano è intonato con rabbia e frustrazione da Macheath subito dopo aver appreso di essere stato condannato a morte. Per «Tyburn Tree» si intende la forca: Tyburn era il villaggio del Middlesex in cui si eseguivano le sentenze capitali.

In The Beggar’s Opera (1728), written by John Gay, with music drawn mostly from traditional repertoire and arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch, the tune of Greensleeves also finds its place. This piece is sung in anger and frustration by Macheath soon after learning that he was sentenced to death. «Tyburn Tree» means the gallows: Tyburn was the Middlesex village where capital punishment was carried out.

In The Beggar’s Opera (1728), written by John Gay, with music drawn mostly from traditional repertoire and arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch, the tune of Greensleeves also finds its place. This piece is sung in anger and frustration by Macheath soon after learning that he was sentenced to death. «Tyburn Tree» means the gallows: Tyburn was the Middlesex village where capital punishment was carried out.

Igudesman & Joo alle prese con una fastidiosa allergia del violinista per la musica di Chopin.

I brani del compositore polacco citati da Joo sono, nell’ordine:

– lo Studio in fa minore, n. 1 delle Trois nouvelles Études composte per la Méthode des Méthodes di Moscheles e Fétis (1840);

– il Valzer in mi minore del 1830, pubblicato postumo [1:02];

– lo Studio in fa minore op. 25 n. 2 [1:35];

– la Ballata (n. 4) in fa minore op. 52 [1:56].

Igudesman, afflitto dall’allergia, vi trova affinità con Oči čёrnye, la canzone pseudo-russa (*) resa celebre da Fëdor Šaljapin; e, a un certo punto, perfino con Happy Birthday to You.

(*) Il testo è di un ucraino, Evgen Pavlovič Hrebinka, la musica di un tedesco, Florian Hermann.

P.D.Q. Bach ovvero Peter Schickele (1935 - 2024): Eine kleine Nichtmusik (1977). The New York Pick-up Ensemble, dir. Peter Schickele.

Ecco un quodlibet alquanto irriverente. Se non riuscite a individuare tutte le composizioni citate, oltre ovviamente alla serenata quasi omonima (K 525) di Mozart, ne potete trovare qui di seguito i titoli, elencati in ordine di apparizione 😀

I movimento:

– Anonimo: Turkey in the Straw [0:06]

– Liszt: Concerto per pianoforte e orchestra n. 1 [0:29]

– Brahms: Sinfonia n. 3, IV movimento [0:32]

– Mozart: duetto «Là ci darem del mano» dal Don Giovanni [0:39]

– Mozart: Concerto per pianoforte n. 23, I movimento [0:46]

– Mozart: «Voi che sapete» dalle Nozze di Figaro [0:53]

– Anonimo: Canto dei battellieri del Volga [0:58]

– Anonimo: D’ye ken John Peel? (canzone tradizionale inglese) [1:17]

– Mozart: Sinfonia n. 1, I movimento [1:25]

– Anonimo: El jarabe tapatio [1:33]

– Mozart: «Voi che sapete» dalle Nozze di Figaro [1:40]

– Rachmaninov: Concerto per pianoforte n. 2, I movimento [1:47]

– Sousa: The Thunderer [2:11]

– Beethoven: Sinfonia n. 7, IV movimento [2:14]

– Mozart: Sinfonia n. 41 (Jupiter), IV movimento [2:32]

– Dvořák: Sinfonia n. 9 (Dal Nuovo Mondo), I movimento [2:37]

– Brahms: Sinfonia n. 3, IV movimento [2:40]

– Brahms: Sinfonia n. 4, I movimento [2:50]

– Händel: «For Unto Us a Child Is Born» dal Messiah [3:03]

– Beethoven: Sinfonia n. 5, IV movimento [3:13]

– Emmett: I wish I was in Dixie [3:23]

– Šostakovič: Sinfonia n. 9, I movimento [3:35]

– Čajkovskij: «Marcia» dallo Schiaccianoci [3:44]

II movimento:

– Foster: Jeannie with the light brown hair [4:01]

– Čajkovskij: Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt [4:38]

– Anonimo: Mary had a little lamb (canzoncina infantile) [4:52]

– Čajkovskij: scena dal Lago dei cigni [5:07]

– Beethoven: Concerto per pianoforte n. 3, I movimento [5:20]

– Rimskij-Korsakov: Shahrazad, Leitmotiv del violino solista [5:20]

– Franck: Sinfonia in re minore, I movimento [5:20]

– Mendelssohn: Frühlingslied, n. 6 dei Lieder ohne Worte op. 62 [5:33]

– Brahms: Sinfonia n. 4, I movimento [5:40]

– Anonimo (forse Davide Rizzio): Auld Lang Syne [5:53]

– Verdi: «Vedi, le fosche notturne spoglie» dal Trovatore [6:16]

– Wagner: Preludio da Tristan und Isolde [6:31]

– Anonimo: Alouette (canzoncina infantile) [6:48]

– Tema B-A-C-H (SI♭-LA-DO-SI) [7:04]

– Rachmaninov: Concerto per pianoforte n. 2, III movimento [7:12]

III movimento:

– Anonimo: Here We Go Loopty Loo (canzoncina infantile) [7:53]

– Beethoven: Sinfonia n. 5, I movimento [8:14]

– Von Tilzer: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (inno ufficioso del baseball negli Stati Uniti) [8:36]

– Musorgskij: tema dell’incoronazione da Boris Godunov [8:55]

– Anonimo: Oh, Dear, What Can the Matter Be? (canzoncina infantile) [9:12]

– Rimskij-Korsakov: Shahrazad, tema del giovane principe [9:23]

IV movimento:

– Foster: Oh, Susanna [9:56]

– Rossini: galop dalla sinfonia del Guillaume Tell [10:11]

– Schubert: Marcia militare [10:15]

– Franck: Sinfonia in re minore, III movimento [10:19]

– Sullivan: «Miyasama» da The Mikado [10:19]

– Grieg: «Nell’antro del re della montagna» da Peer Gynt [10:23]

– Schubert: Erlkönig [10:26]

– Musorgskij: tema dell’incoronazione da Boris Godunov [10:26]

– Anonimo: Ah!, vous dirai-je, maman (canzoncina infantile) [10:32]

– Franck: Sinfonia in re minore, III movimento [10:36]

– Foster: Old Black Joe (canto tradizionale) [10:44]

– Mozart: Sinfonia n. 29, IV movimento [10:50]

– Stravinskij: dal finale di Pétrouchka [10:55]

– Humperdinck: Hänsel und Gretel, atto I, scena 1a [11:03]

– Offenbach: «Galop enfernal» da Orphée aux enfers [11:07]

– Schumann: Sinfonia n. 1 (Frühlingssymphonie), I movimento [11:11]

– Anonimo: Travadja La Moukère [11:15]

– Musorgskij: «La Grande Porta di Kiev» dai Quadri di un’esposizione [11:19]

– Autore incerto: Westminster Quarters [11:20]

– Beethoven: Sinfonia n. 5, I movimento [11:20]

– R. Strauss: Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche [11:30]

Charles Dieupart (1676 - 1751): Menuet, n. 6 della Suite in fa minore per flauto o violino e basso continuo (1701). Il Giardino Armonico, dir. Giovanni Antonini. Coreografia: Musica et Saltatoria.

Franz Schubert (1797 - 1828): Minuetto in do diesis minore D 600 (1814), eseguito insieme con il Trio in mi maggiore D 610. Jörg Demus, pianoforte.

Scene tratte dal film di Roman Polański Per favore, non mordermi sul collo! (The Fearless Vampire Killers, 1967). La musica è di Krzysztof Komeda (pseudonimo di Krzysztof Trzciński, 1931 - 1969), il quale compose le colonne sonore di altri due film di Polański, Il coltello nell’acqua (1962) e Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Coreografia di Tutte Lemkow (1918 - 1991).

P.D.Q. Bach (alias Peter Schickele; 17 luglio 1935 - 2024): Grand Serenade for an Awful Lot of Winds and Percussion (1992). Turtle Mountain Naval Base Tactical Wind Ensemble, dir. Peter Schickele.

Grand Entrance : la solennità un po’ statica, severa ma non seria, del I movimento è punteggiata dai versi di alcuni pennuti che incautamente si sono introdotti nell’auditorium; non vorrei dirlo, ma… insomma… peggio per loro.

Simply Grand Minuet : in questo minuetto reboante la banda si fa accompagnare dal suono di ance e bocchini staccati dai rispettivi aerofoni; l’effetto nel complesso ricorda un po’ i richiami da caccia: forse i suonatori vorrebbero catturare altri volatili da sacrificare sull’altare di P.D.Q.

Romance in the Grand Manner : in sostanza è una suggestiva armonizzazione di Old Folks at Home ovvero Swanee River, celeberrimo minstrel song composto da Stephen Foster nel 1851.

Rondo Mucho Grando : il brano più esteso della suite è introdotto da un triplice rullo di timpano e tamburo militare, che si risolve in uno spaventoso crasho grosso quando l’armamentario delle percussioni rovina (fortuitamente?) a terra. Il tema principale del rondò, semplice e orecchiabile (più o meno), s’incrocia di continuo con segnali militari (carica!), con la fanfara che all’ippodromo annuncia l’inizio delle corse e con suggestioni blues. La sezione centrale si apre con una citazione di You Gotta Be a Football Hero, subito metamorfizzato nel tema iniziale del Quartetto n. 7 (op. 59 n. 1) di Beethoven. Una sirena sancisce la fine delle ostilità.

Grand Entrance: in his static solemnity, stern but not serious, the 1st movement is dotted by the cries of some birds who recklessly entered the auditorium; I don’t want to say it, but– well– worse for them.

Simply Grand Minuet: playing this booming minuet the band is accompanied by reeds and mouthpieces detached from their respective aerophones; the overall effect is somewhat reminiscent of hunting calls: maybe our players would like to capture other birds to be sacrificed on the altar of P.D.Q.

Romance in the Grand Manner: it substantially is a suggestive harmonization of Old Folks at Home or Swanee River, a famous minstrel song composed by Stephen Foster in 1851.

Rondo Mucho Grando: the most extensive movement of the Serenade is introduced by a triple roll performed by timpani and snare drum, which results in a frightening crasho grosso when all the percussion instruments fall (fortuitously?) to the ground. The main theme of the Rondo, (almost) simple and catchy, constantly intersects with military signals (charge!), the fanfare that announces the start of races at the hippodrome and bluesy tones. The middle section opens with a quote from You Gotta Be a Football Hero, which is immediately metamorphosed into the first theme of Beethoven’s Quartet no. 7 (op. 59 n. 1). A siren marks the end of hostilities.

Louis Andriessen (1939 - 1° luglio 2021): De negen Symfonieën van Beethoven voor promenade-orkest en ijscobel (1970).

Gabriel Fauré (12 maggio 1845 - 1924) e André Messager (1853-1929): Souvenirs de Bayreuth, «Fantaisie en forme de quadrille sur les thèmes favoris de L’Anneau du Nibelung de Richard Wagner» per pianoforte a 4 mani (c1880). Pierre-Alain Volondat e Patrick de Hooge.

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841 - 1894): Souvenirs de Munich, «Fantaisie en forme de quadrille sur les thèmes favoris de Tristan et Isolde de Wagner» (1885-86). Pinuccia Giarmanà e Alessandro Lucchetti.