David Diamond (1915 - 13 giugno 2005): Music for Shakespeare’s «Romeo and Juliet», suite per orchestra (1947). New York Chamber Symphony Orchestra, dir. Gerard Schwarz.

- Overture: Allegro Maestoso

- Balcony Scene: Andante semplice [3:10

- Romeo and Friar Laurence: Andante [8:16

- Juliet and her Nurse: Allegretto scherzando [11:58

- The Death of Romeo and Juliet: Andante sospirando [14:11]

L’approfondimento

di Pierfrancesco Di Vanni

David Diamond: melodie americane tra trionfi e avversità

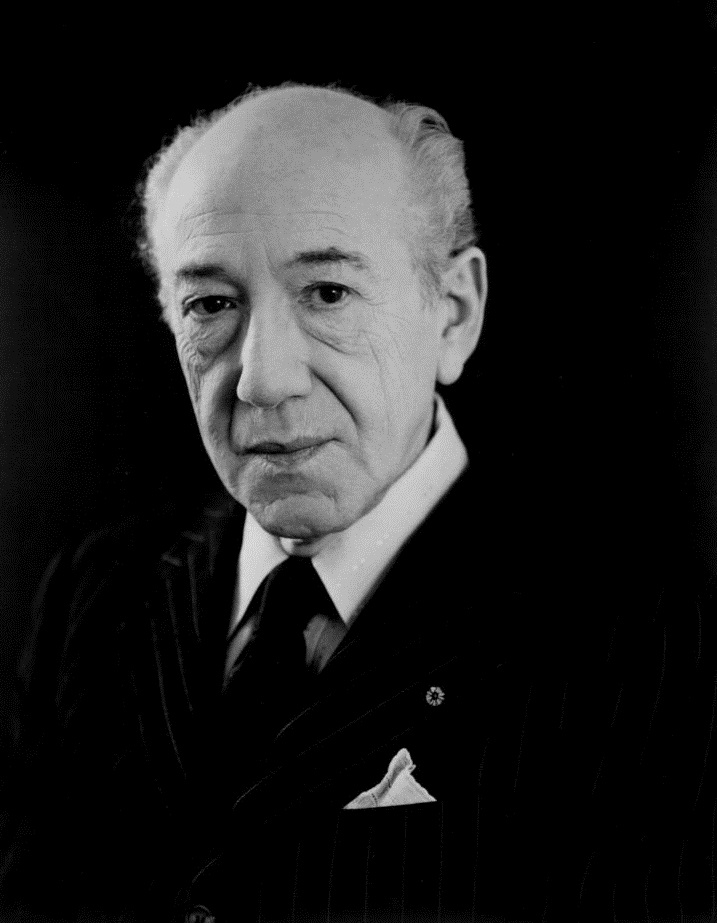

David Diamond viene oggi ricordato come una figura di spicco tra i compositori della sua generazione negli Stati Uniti. Le sue prime opere si distinguono per l’uso di armonie triadiche, spesso con ampie spaziature che conferiscono loro un carattere tipicamente americano, sebbene alcune composizioni riflettano consapevolmente un’influenza stilistica francese. Con il tempo, il suo linguaggio musicale si orientò verso un maggiore cromatismo.

Formazione prestigiosa e inizi di carriera

Nato a Rochester, New York, Diamond intraprese studi musicali approfonditi presso il Cleveland Institute of Music e la Eastman School of Music, dove fu allievo di Bernard Rogers. Perfezionò la sua formazione ricevendo lezioni private da figure di calibro internazionale come Roger Sessions a New York City e Nadia Boulanger a Parigi. Il suo talento fu presto riconosciuto con numerosi premi, tra cui ben tre Guggenheim Fellowship, che ne attestarono il precoce valore.

Opere significative e contributi multimediali

Il suo brano più celebre è Rounds (1944) per orchestra d’archi, un pezzo che gode di vasta popolarità. Il suo catalogo compositivo è tuttavia ampio e diversificato, includendo 11 sinfonie (l’ultima completata nel 1993), diversi concerti (tra cui tre per violino), 11 quartetti d’archi, musica per ensemble di fiati, altra musica da camera, pezzi per pianoforte e composizioni vocali. Diamond estese la propria attività anche al mondo dei media, componendo il tema musicale per il programma radiofonico della CBS Hear It Now (1950–51) e per la sua successiva versione televisiva, See It Now (1951–58).

L’insegnamento e l’influenza sulle nuove generazioni

Oltre alla sua attività compositiva, Diamond fu una figura influente nell’ambito accademico. Venne nominato compositore-in-residenza onorario della Seattle Symphony e fu per lungo tempo membro della facoltà della prestigiosa Juilliard School. Tra i suoi studenti più noti si annoverano Alan Belkin, Robert Black, Kenneth Fuchs, Albert Glinsky, Daron Hagen, Adolphus Hailstork, Anthony Iannaccone, Philip Lasser, Lowell Liebermann, Alasdair MacLean, Charles Strouse, Francis Thorne, Kendall Durelle Briggs ed Eric Whitacre. È inoltre riconosciuto il suo ruolo di consulente per Glenn Gould, in particolare per il suo Quartetto d’archi op. 1.

Riconoscimenti ufficiali, le sfide di una vita controcorrentee la morte

Il valore artistico del compositore ricevette importanti riconoscimenti ufficiali, tra cui la National Medal of Arts (1995) e la Edward MacDowell Medal (1991). Tuttavia, la sua carriera non fu priva di ostacoli. Diamond fu apertamente omosessuale in un’epoca in cui ciò non era socialmente accettato e lui stesso riteneva che la sua progressione professionale fosse stata rallentata da omofobia e antisemitismo. Un necrologio su The Guardian sottolinea come, dopo un periodo di grande successo negli anni ’40 e primi ’50, l’ascesa delle scuole seriali e moderniste negli anni ’60 e ’70 lo relegò in secondo piano. Similmente, il New York Times lo descrisse come «un importante compositore americano la cui precoce brillantezza negli anni ’40 fu eclissata dal predominio della musica atonale», collocandolo in una "generazione dimenticata" di grandi sinfonisti americani insieme a Howard Hanson, Roy Harris, William Schuman, Walter Piston e Peter Mennin. Lo stesso New York Times suggerì che i problemi di carriera di Diamond potessero essere stati esacerbati anche dalla sua "personalità difficile", citando un’intervista del 1990 in cui il compositore ammetteva di essere stato un giovane emotivo e diretto, propenso a creare scene pubbliche con figure autorevoli come i direttori d’orchestra. Morì il 13 giugno 2005 nella sua casa di Brighton, New York, a causa di un’insufficienza cardiaca.

Music for Shakespeare’s «Romeo and Juliet»: analisi

Con questa suite sinfonica Diamond ha dimostrato l’attitudine a tradurre la potenza drammatica e la complessità emotiva del capolavoro shakespeariano con l’adozione di un linguaggio musicale ricco e accessibile. Composta durante il suo periodo di maggior successo, la suite riflette la sua maestria orchestrale e il suo stile prevalentemente tonale, arricchito da inflessioni modali e da un uso sapiente del cromatismo per accentuare la tensione emotiva. L’opera, pur essendo radicata nella tradizione, presenta una freschezza e una vitalità che la rendono un ascolto coinvolgente.

L’ouverture funge da preludio, introducendo l’atmosfera generale della tragedia, accennando ai temi principali del conflitto e dell’amore contrastato. Il movimento si apre con una fanfara potente e maestosa affidata agli ottoni, caratterizzata da armonie ampie e brillanti, tipiche di un certo "suono americano" che Diamond sapeva evocare. Questa introduzione imposta un tono eroico e quasi regale, ma con un sottofondo di tensione. Ben presto, gli archi introducono un tema lirico e ampio, dal carattere appassionato e romantico, che potrebbe rappresentare l’amore nascente tra i due protagonisti. La scrittura per archi è fluida e cantabile. Diamond sviluppa questi materiali contrastanti: sezioni più ritmiche e percussive, con accenti marcati e un’energia propulsiva, sembrano dipingere il conflitto tra le famiglie Montecchi e Capuleti. I legni intervengono con passaggi più agili e talvolta delicati, aggiungendo colore e varietà timbrica. L’orchestrazione è ricca e piena, sfruttando l’intera gamma dinamica dell’orchestra e costruendo progressivamente verso climax sonori di grande impatto, quasi cinematografico. L’armonia rimane prevalentemente tonale, ma con un uso espressivo di dissonanze e modulazioni che ne arricchiscono la tavolozza emotiva senza mai sfociare nell’atonalità. L’Allegro maestoso cattura efficacemente la grandezza della tragedia e la passione che la pervade.

Il secondo movimento è la rappresentazione musicale della celeberrima scena del balcone, l’incontro segreto e appassionato tra Romeo e Giulietta, culmine del loro amore giovanile. Il tempo Andante semplice preannuncia la natura intima e tenera del movimento. La musica si fa subito più rarefatta e delicata rispetto all’ouverture. Un flauto solista introduce una melodia dolce e sognante, quasi un sospiro, che incarna la voce di Giulietta. Gli archi, spesso con sordina, creano un tappeto sonoro etereo e brillante, mentre l’arpa aggiunge tocchi di magia e romanticismo con i suoi arpeggi. Il dialogo musicale tra i legni (flauto, oboe, clarinetto) evoca le tenere conversazioni tra i due amanti. Le melodie sono liriche, espressive e cariche di un lirismo cantabile che riflette la purezza e l’intensità del loro sentimento. L’armonia è lussureggiante e romantica, prevalentemente tonale ma con un uso più marcato di cromatismi e accordi arricchiti (settime, none) per esprimere la profondità dell’emozione. Diamond costruisce con maestria un crescendo emotivo che, pur rimanendo contenuto nella dinamica, raggiunge un apice di intensità prima di dissolversi in una conclusione sospesa e sognante, lasciando l’ascoltatore immerso nell’incanto della scena. La scrittura per legni qui potrebbe rivelare quell’influenza francese menzionata nella biografia del compositore.

Il terzo movimento è ispirato alla scena nella quale Romeo si confida con Frate Lorenzo, cercando consiglio e aiuto. La scena implica un misto di speranza giovanile e la saggezza, forse un po’ preoccupata, del frate. L’atmosfera cambia nettamente. L’Andante qui ha un carattere più grave e riflessivo. Il movimento si apre con un tema solenne e quasi austero negli archi bassi e nel fagotto, che potrebbe rappresentare la figura saggia e autorevole di Frate Lorenzo. Le linee melodiche hanno a tratti un andamento modale, quasi da corale, che sottolinea la natura religiosa del frate.

A questo materiale si contrappongono interventi più agitati e appassionati, spesso affidati agli archi acuti o a brevi frammenti dei legni, che esprimono l’impazienza e l’ardore di Romeo. L’orchestrazione è più scura e densa rispetto al movimento precedente, con un maggior peso dato agli strumenti gravi. Diamond sviluppa un vero e proprio dialogo musicale, alternando momenti di calma riflessione a improvvisi slanci emotivi. La tensione armonica aumenta gradualmente, con un uso più frequente di cromatismi che suggeriscono le preoccupazioni del frate e il destino incerto degli amanti. Il movimento si conclude in modo pensoso, quasi interrogativo, lasciando una sensazione di presagio.

Il quarto movimento dipinge l’interazione tra Giulietta e la sua Nutrice, una figura affettuosa ma anche loquace e talvolta comica. C’è un misto di impazienza giovanile (di Giulietta) e di bonaria prolissità (della Nutrice). L’indicazione Allegretto scherzando è perfettamente realizzata. La musica è leggera, vivace e piena di spirito. I legni (flauto, oboe, clarinetto in particolare) sono protagonisti con passaggi rapidi, quasi "chiacchiericci", che evocano la garrulità della Nutrice e la giocosità della scena. Gli archi contribuiscono con pizzicati agili e accompagnamenti staccati che accentuano il carattere scherzoso. Il ritmo è brioso e danzante, con frequenti cambi di metro o accenti spostati che conferiscono un’aria di imprevedibilità e umorismo. Non mancano brevi episodi più lirici e teneri, forse a rappresentare i pensieri amorosi di Giulietta, che si intrecciano con le sezioni più giocose. L’orchestrazione è trasparente e brillante, e anche qui la scrittura per legni, arguta e colorata, potrebbe richiamare un’estetica francese. È un movimento che dimostra la versatilità di Diamond nel passare da atmosfere intense a momenti di leggerezza.

L’ultimo movimento rappresenta il tragico epilogo della storia: la morte dei due amanti. "Sospirando" suggerisce il dolore e l’agonia. Questa parte si apre con un’atmosfera di profonda desolazione e tragedia. Il tempo è lento, il carattere funereo. Gli archi gravi, i tromboni e il corno inglese (o un oboe dal timbro particolarmente dolente) intonano melodie frammentate, cariche di dolore e "sospiri" musicali, spesso realizzati con appoggiature e risoluzioni cromatiche. L’armonia si fa decisamente più cromatica e dissonante, esprimendo l’angoscia e la disperazione. Diamond costruisce la tensione attraverso lunghi crescendo che sfociano in accordi potenti e drammatici, seguiti da improvvisi silenzi o momenti di estrema rarefazione sonora, come se la musica stessa ansimasse per il dolore. L’uso del timpano con rulli sommessi o colpi secchi accentua la fatalità della situazione. Le linee melodiche sono spezzate, piene di intervalli che esprimono sofferenza (come le seconde minori o i tritoni). Verso la conclusione, dopo l’apice della disperazione, la musica sembra placarsi in una sorta di rassegnazione tragica, forse con un accenno a una bellezza ultraterrena, ma il senso predominante è quello della perdita irreparabile. L’orchestra viene utilizzata in tutta la sua potenza espressiva, dai pianissimi più desolati ai fortissimi più strazianti, chiudendo la suite con un senso di catarsi dolorosa.

Nel complesso, la suite è un’opera di grande forza drammatica e raffinatezza orchestrale. Il compositore riesce a catturare l’essenza di ogni scena chiave della tragedia, utilizzando un linguaggio tonale arricchito da elementi moderni, senza mai perdere la comunicativa emotiva. La sua abilità nel creare atmosfere contrastanti, dalla tenerezza lirica dell’amore giovanile alla cupezza della tragedia, e la sua scrittura idiomatica per l’orchestra, confermano il suo status di importante compositore americano del suo tempo. L’opera è un eccellente esempio di musica a programma del XX secolo che, pur non essendo innovativa come le avanguardie contemporanee, dimostra una profonda comprensione del dramma e una notevole maestria compositiva.

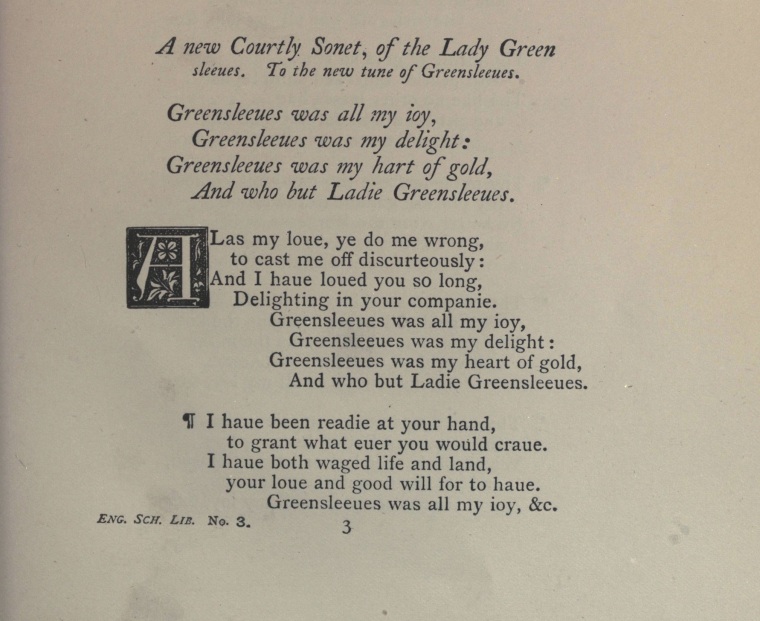

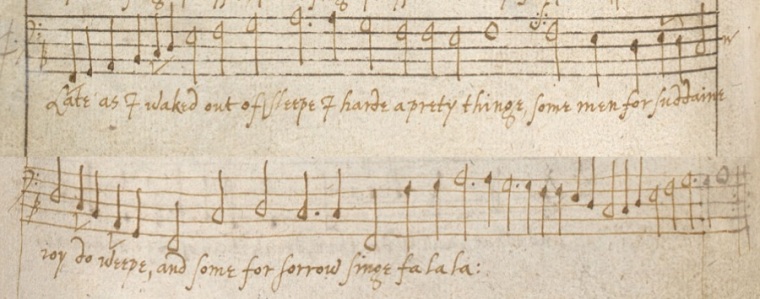

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

English translation: please

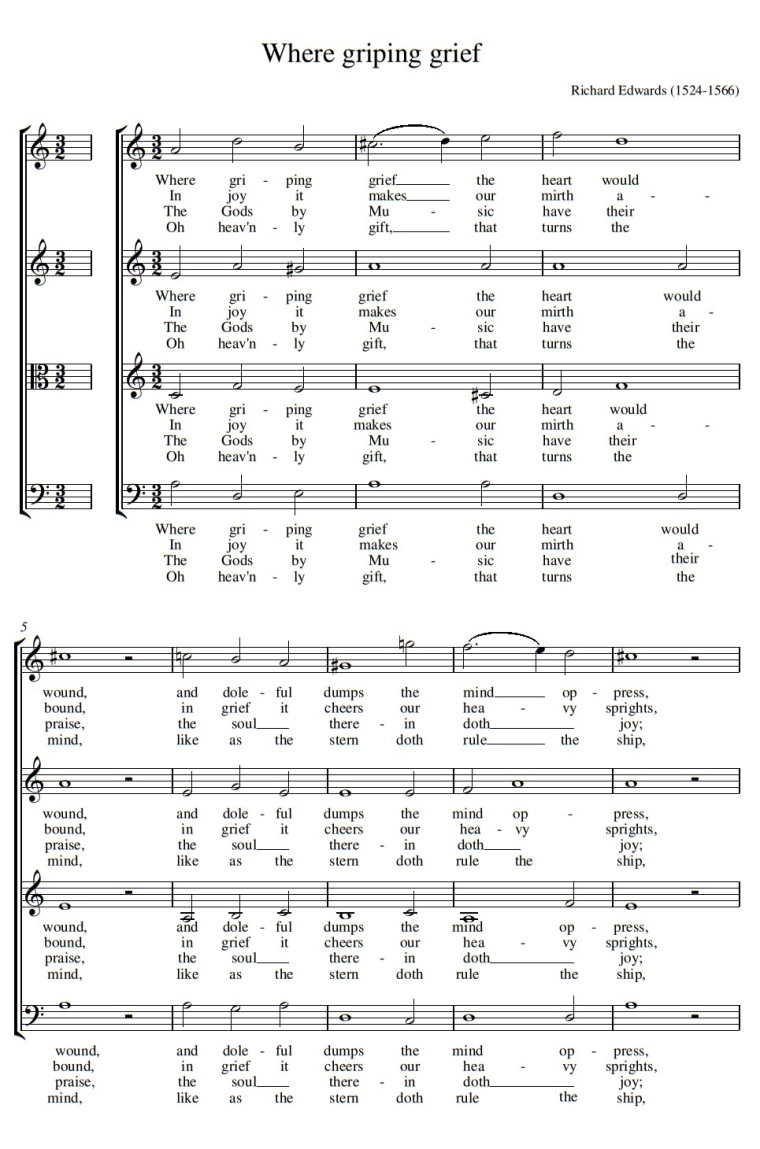

English translation: please  Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

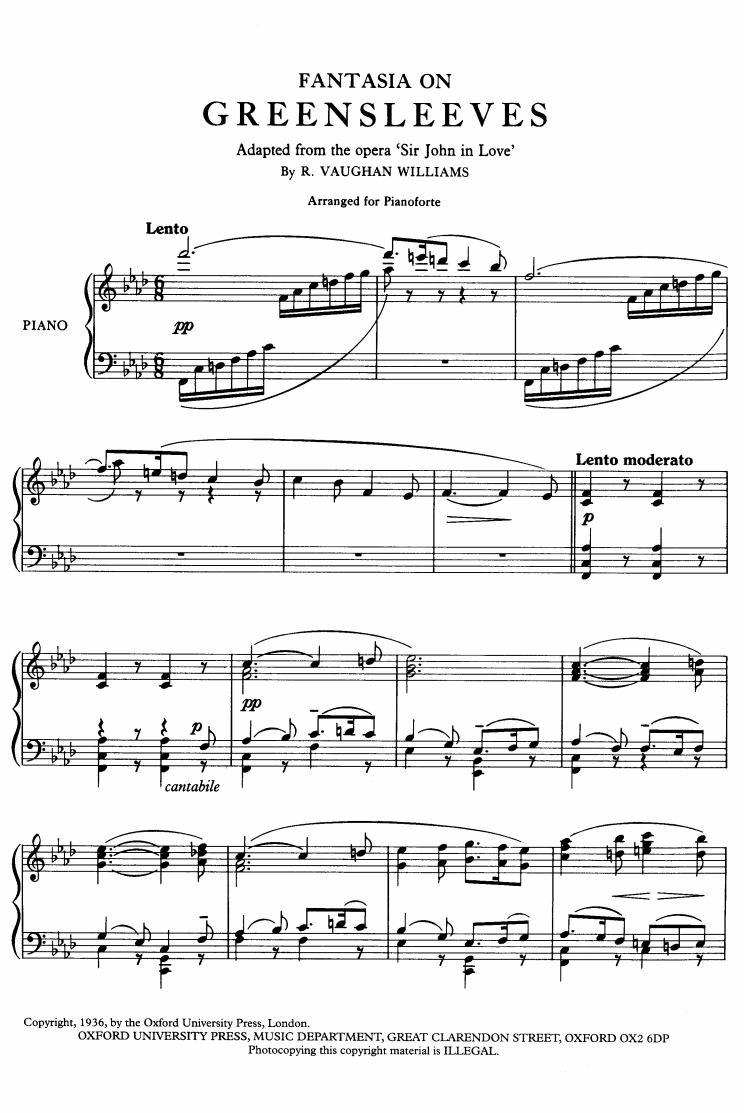

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.

Forse, ascoltando queste recercadas vi sarà venuta in mente Greensleeves: una ragione c’è, ora vedremo di che si tratta.

Eugène Delacroix: Hamlet et Horatio au cimetière (1839), Paris, Louvre

Eugène Delacroix: Hamlet et Horatio au cimetière (1839), Paris, Louvre

Dopo aver ascoltato

Dopo aver ascoltato