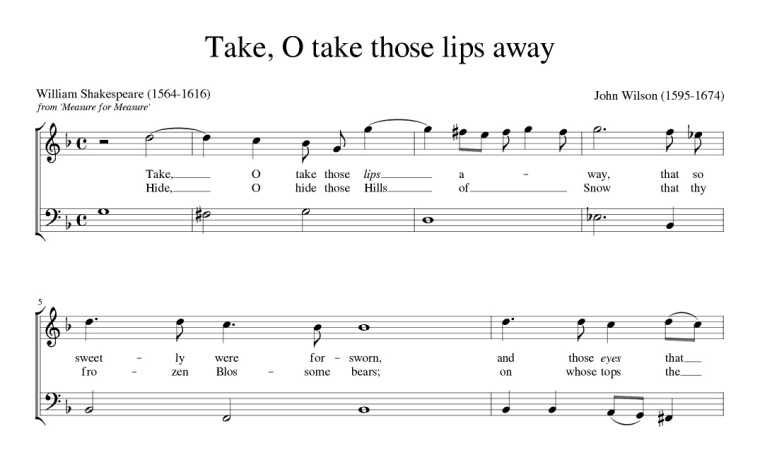

Kurt Weill (1900 - 1950): cinque brani dalla Kleine Dreigroschenmusik für Blasorchester (1928). London Sinfonietta, dir. David Atherton.

- Die Moritat von Mackie Messer

- Anstatt-dass-Song [2:12]

- Die Ballade vom angenehmen Leben [3:59]

- Tango-Ballade [6:53]

- Kanonen-Song [9:35]

La Kleine Dreigroschenmusik non è propriamente una suite tratta dalle musiche scritte per l’Opera da tre soldi, ma piuttosto una composizione del tutto autonoma, dove i temi della partitura originale sono trattati con libertà e arguzia: la celebre «Moritat von Mackie Messer», per esempio, è fusa con il «Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit» in un insieme di mirabile finezza e eleganza.

Pensata per 12 strumenti a fiato, pianoforte, banjo, chitarra, bandoneon e percussione, la Kleine Dreigroschenmusik fu eseguita per la prima volta durante un ballo all’Opera di Berlino nel febbraio 1929, sotto la direzione di Otto Klemperer.

Ed ecco una vera chicca: il «Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit menschlichen Strebens» cantato nientemeno che da Bertolt Brecht in carne e adenoidi.

Der Mensch lebt durch den Kopf,

sein Kopf reicht ihm nicht aus,

versuch´ es nur, von deinem Kopf

lebt höchstens eine Laus.

Denn für dieses Leben

ist der Mensch nicht schlau genug,

niemals merkt er eben

diesen Lug und Trug.

Ja, mach nur einen Plan,

sei nur ein großes Licht

und mach dann noch ´nen zweiten Plan,

gehen tun sie beide nicht.

Denn für dieses Leben

ist der Mensch nicht schlecht genug,

doch sein höh’res Streben

ist ein schöner Zug.

Ja, renn nur nach dem Glück!

Doch renne nicht zu sehr,

denn alle rennen nach dem Glück,

das Glück rennt hinterher!

Denn für dieses Leben

ist der Mensch nicht anspruchslos genug,

drum ist all sein Streben

nur ein Selbstbetrug.

Der Mensch ist gar nicht gut

drum hau ihn auf den Hut

hast du ihn auf den Hut gehaut

dann wird er vielleicht gut.

Denn für dieses Leben

ist der Mensch nicht gut genug

darum haut ihn eben

ruhig auf den Hut.

(L’uomo vive con la testa, ma questa non gli basta. Provaci pure, dalla tua testa ci campa al massimo un pidocchio. Per stare a questo mondo l’uomo non è abbastanza furbo: manco si accorge dei trucchi e degli imbrogli.

Prepara un bel progetto da grande luminare! Poi pensa a un altro bel progetto, e prova a farli funzionare. Per stare a questo mondo l’uomo dev’essere cattivo. Le sue belle aspirazioni, tutt’al più gli fanno onore.

Rincorri la fortuna, però non correr troppo, tutti inseguono la fortuna e invece è lei a inseguire te. Per stare a questo mondo l’uomo accampa troppe pretese. Le belle aspirazioni non sono che un inganno.

L’uomo di certo non è buono, prova a dargli una strigliata. Chissà se forse allora un po’migliorerà. Per stare a questo mondo l’uomo non è abbastanza buono, non ti crucciare, quindi, e dagli una strigliata.)

L’approfondimento

di Pierfrancesco Di Vanni

Kurt Weill: l’architetto sonoro tra l’Avanguardia di Berlino e i riflettori di Broadway

Kurt Julian Weill è stato un influente compositore tedesco, successivamente naturalizzato statunitense, la cui carriera si è divisa tra il teatro d’avanguardia europeo e i grandi musical americani.

Origini e formazione in Germania

Nato a Dessau in una famiglia ebraica ashkenazita – il padre, Albert Weill, era chazan (cantore) della sinagoga locale – il giovane iniziò la sua formazione musicale fin dall’infanzia. Dopo i primi studi presso il Teatro regio ducale della sua città, nel 1915 passò sotto la guida di Albert Bing. Su incoraggiamento di questi, nel 1918 si iscrisse alla Hochschule für Musik di Berlino per studiare con Engelbert Humperdinck (composizione) e con Rudolf Krasselt (direzione d’orchestra). Tuttavia, problemi finanziari e una certa alienazione dall’ambiente accademico lo spinsero a tornare a Dessau l’anno seguente, dove lavorò come maestro sostituto per Bing e Hans Knappertsbusch, e in seguito come direttore di una piccola compagnia d’opera a Lüdenscheid. Il punto di svolta accademico avvenne nel 1920, quando Weill tornò a Berlino ma, su consiglio dell’amico Hermann Scherchen, scelse di non studiare con Franz Schreker, preferendo iscriversi ai corsi speciali tenuti da Ferruccio Busoni presso l’Akademie der Künste, frequentandoli per tre anni. Si perfezionò anche con l’assistente di Busoni, Philipp Jarnach: è a questo periodo che risale il suo primo balletto per bambini, Zaubernacht (1922).

L’apice tedesco: Nuova Oggettività e la partnership con Brecht

A metà degli anni ’20, Weill emerse come figura chiave della Nuova Oggettività (Neue Sachlichkeit), un movimento che portava temi sociali e politici in musica. I suoi primi lavori significativi, come il Concerto per violino e fiati (1925) e l’opera Der Protagonist (1926), riflettono questa nuova sensibilità. In questi anni, il compositore frequentò assiduamente i circoli espressionisti berlinesi, in particolare il Novembergruppe, entrando in contatto con intellettuali di spicco come Philipp Jarnach, Hanns Eisler e Bertolt Brecht.

La collaborazione con Brecht

La sua collaborazione con il drammaturgo Georg Kaiser portò al successo di Der Protagonist, il quale gli valse una commissione per una breve opera da camera, per la quale Weill attinse ai Mahagonny-Gesänge, testi tratti dalla raccolta poetica Die Hauspostille di Bertolt Brecht. Iniziò così un sodalizio artistico, benché breve (solo tre anni), che rivoluzionò il teatro novecentesco. I frutti di questa collaborazione includono:

– il Mahagonny-Songspiel (Baden-Baden, 1927);

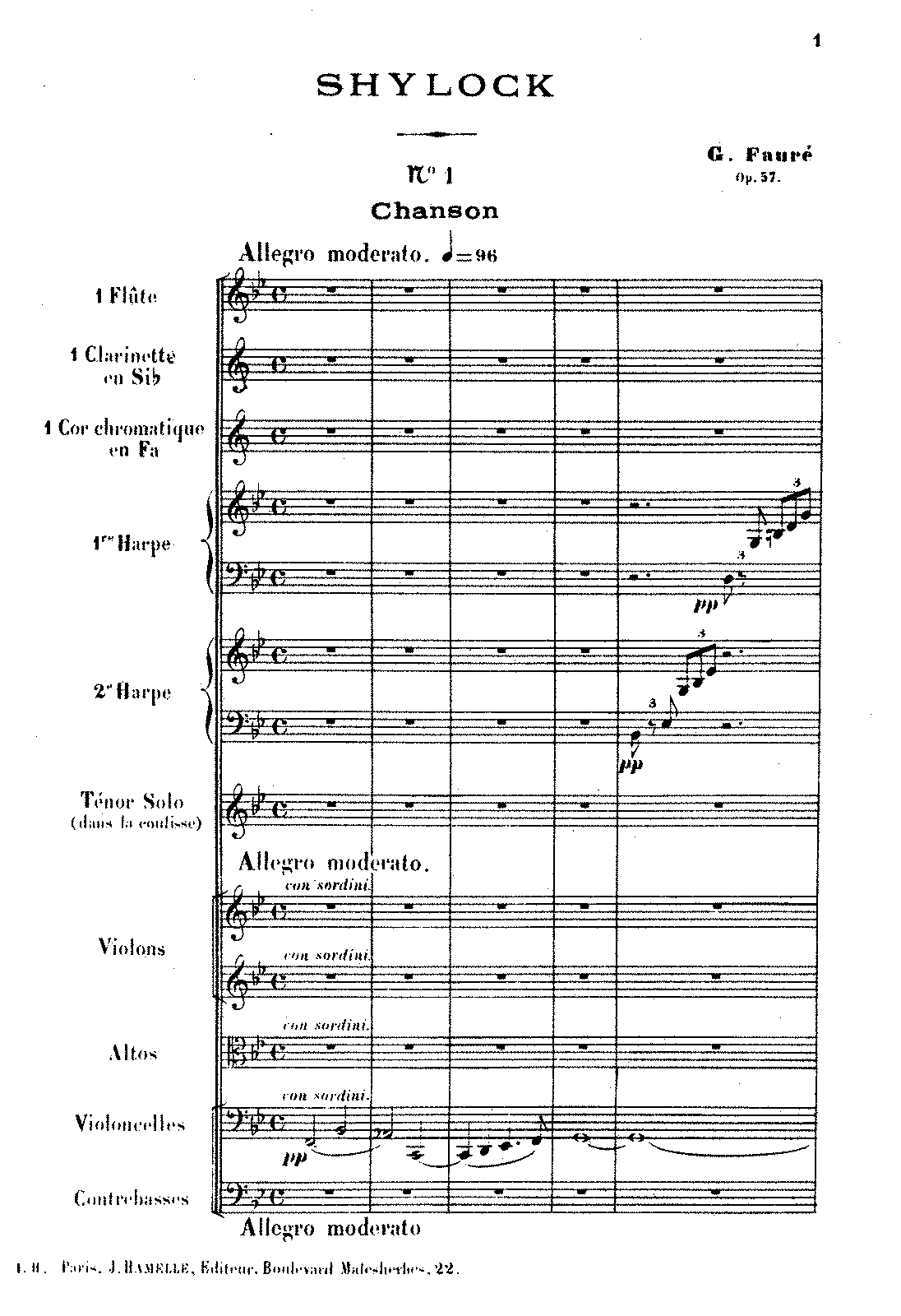

– Die Dreigroschenoper (L’opera da tre soldi, 1928): ispirata dalla Beggar’s Opera (L’opera del mendicante, 1728) di John Gay e Johann Christoph Pepusch, vide il ruolo di Jenny interpretato da Lotte Lenya, cantante e attrice viennese, sposata da Weill nel 1926;

– Happy End (1929), commedia satirica;

– Ascesa e caduta della città di Mahagonny (1930), una vera e propria opera in tre atti che rielabora i materiali del precedente Songspiel.

Grazie al suo “grandissimo senso teatrale”, Weill raggiunse fama e stima in Germania e in tutta Europa.

L’esilio forzato: Parigi e Londra

Nonostante la sua crescente notorietà e il successo del suo ultimo lavoro con Kaiser, Der Silbersee (Il lago d’argento), l’avvento del nazismo costrinse Weill, di origine ebraica, a fuggire dalla Germania nel 1933. I suoi anni di esilio in Europa furono complessi, sebbene ricevette l’aiuto di colleghi stimati come Bruno Walter, Darius Milhaud e Arthur Honegger. A Parigi scrisse il balletto Die sieben Todsünden (I sette peccati capitali, 1933) su soggetto di Brecht, e il musical Marie Galante (1934), su testo di Jacques Deval. Dopo un breve periodo nel Regno Unito, Weill si preparò a lasciare definitivamente l’Europa.

La riconversione americana: da opera lirica a Broadway

Nel 1935 Weill si rifugiò negli Stati Uniti, inizialmente per supervisionare la produzione di Der Weg der Verheissung (rappresentato l’anno seguente come The Eternal Road), un lavoro dedicato alla storia del popolo ebraico. Gli anni americani segnarono un distacco volontario dalla musica d’arte europea: Weill si dedicò quasi esclusivamente al teatro di Broadway, a Hollywood e alla Radio americana, affermandosi in un nuovo genere. Dopo alcuni insuccessi iniziali (The Eternal Road o Johnny Johnson), egli raggiunse il successo con importanti musical, spesso collaborando con il paroliere Maxwell Anderson. Tra le sue opere più celebri di questo periodo vi sono: l’operetta The Fireband of Florence, l’opera americana Street Scene e Lost in the Stars. Il 19 ottobre 1938 debuttò invece il musical Knickerbocker Holiday, che raggiunse le 168 recite e rese celebre la canzone September Song.

La Kleine Dreigroschenmusik

La Kleine Dreigroschenmusik condensa l’essenza dell’opera più celebre di Kurt Weill e Bertolt Brecht, Die Dreigroschenoper. La strumentazione mette in risalto il carattere tagliente, satirico e volutamente “basso” della partitura, un marchio distintivo del movimento della Nuova Oggettività.

Il primo dei brani qui proposti è il più iconico dell’opera e si presenta immediatamente con un contrasto stridente tra la sua forma musicale – un tipo di ballata medievale cantata da menestrelli itineranti che racconta i crimini di famigerati assassini – e l’eleganza grottesca dell’orchestrazione. La melodia è semplice e armonicamente incisiva, sostenuta da un ritmo costante e leggermente marziale che le conferisce un sapore aspro e un tono quasi beffardo, tipico del cabaret berlinese. Subito dopo, si assiste a una variazione della melodia, dove il clarinetto e altri legni tessono un contrappunto agile, mantenendo la semplicità melodica di base. Le successive ripetizioni vedono i legni predominare, spesso con dinamiche forti. Weill intende prendere le distanze dalla retorica musicale borghese: il pezzo è sfacciatamente popolare, con armonie dissonanti e una strumentazione che evoca l’immagine di un’orchestrina da strada, adatta a raccontare la storia cinica e sanguinaria di Mackie Messer.

Il secondo brano è un esempio perfetto dell’influenza del jazz e della musica da ballo americana sul linguaggio musicale di Weill. Qui si giunge nel regno del foxtrot o dello shimmy, con un ritmo incalzante e una melodia ballabile. L’introduzione è guidata dai legni in un andamento quasi danzante e capriccioso, con frequenti sincopi. La strumentazione è brillante e ironica, con Weill che utilizza i fiati con grande libertà, replicando l’estetica delle prime jazz band. La sincope è onnipresente, creando un senso di precarietà e vivacità, tipico degli sfrenati anni venti. Il pezzo si basa su una serie di contrasti dinamici e tematici che riflettono la natura satirica del testo originale (che parla della caduta degli ideali). La strumentazione più sparsa contribuisce a valorizzare il timbro dei vari solisti e il contrasto tra dolcezza melodica e accompagnamento disincantato.

Il terzo pezzo offre un respiro lirico, pur mantenendo un sottotesto cinico. L’apertura è affidata a un motivo quasi lamentoso, eseguito con grande enfasi melodica, che evoca un tono di falsa nostalgia. La sua melodia è ampia, sentimentale e vivace, con un uso notevole del vibrato e dell’espressività. Il carattere poi si sposta brevemente su un tono più “jazzistico”, con la tromba che interviene con un breve intermezzo ritmico e sincopato, come una parentesi di cabaret decadente: questo inserto è poi interrotto bruscamente e il brano ritorna alla melodia principale. Le armonie sono ricche e talvolta scivolano nella dissonanza, ricordando come anche nei momenti di presunta “piacevolezza” vi sia una nota di fondo amara. L’uso dei fiati bassi (fagotto, tuba) fornisce una base solida e profonda che bilancia l’espressività degli strumenti acuti, mentre l’alternanza tra lirismo esagerato e intrusioni ritmiche spigolose mantiene viva la tensione drammatica.

Il Tango-Ballade è un altro esempio che attinge a generi popolari, deformandoli per esprimere una critica sociale: il tango qui non è romantico, ma lascivo e minaccioso. L’elemento ritmico è predominante fin dall’inizio, stabilendo il caratteristico metro binario del tango, sostenuto da una pulsazione oscura e da percussioni sobrie. Il clima è subito denso, evocando l’atmosfera fumosa e pericolosa dei bassifondi. Il brano è costruito su distinti interventi strumentali: la melodia è spezzata e spesso affidata a strumenti solisti come il sassofono soprano o il clarinetto che suonano con un tono graffiante e sensuale. L’uso del registro grave del sassofono è particolarmente efficace nel creare un senso di bassezza morale e seduzione. Un momento di particolare intensità si verifica con l’entrata della tromba che suona in modo stridulo e penetrante, aggiungendo un elemento di inquietudine, mentre le sezioni orchestrali complete mantengono la ritmica ossessiva del tango, con dinamiche potenti, prima di ritornare a un tono più sommesso e intimo. Il pezzo è notevole per la sua capacità di costruire tensione, con il tango avanza con passo inesorabile, riflettendo la tematica della perdizione e della violenza che permea l’opera di Brecht.

Il quinto brano è un’esplosione di energia cinica, un inno marziale e grottesco che celebra la guerra in modo ironico. Il brano è veloce, quasi frenetico, con un volume sonoro elevato: l’introduzione è un’immediata raffica di ottoni e percussioni che stabiliscono un ritmo di marcia sfrenato e militaristico. Weill qui si concentra sulla sezione degli ottoni, i quali assumono un ruolo preponderante, amplificando la retorica marziale in modo caricaturale. La melodia è energica ma volutamente banale, un inno vuoto e roboante che sottolinea la cieca brutalità della guerra, tipica dell’epos brechtiano. L’interazione tra i legni rapidi (clarinetti e sassofoni) e l’imponenza degli ottoni spinge il brano verso il climax, con Weill che sfrutta appieno le capacità dinamiche e timbriche dell’ensemble di fiati. La conclusione è un fragoroso e ironico accordo finale che lascia un senso di caos organizzato e di critica sociale urlata.

Nel complesso, l’opera è una testimonianza del genio di Weill nel fondere la musica d’arte con gli stili popolari, usando l’orchestrazione per fiati sia per ragioni pratiche (la necessità di un piccolo ensemble nel teatro espressionista), che per forgiare un linguaggio sonoro inconfondibile, cinico e tagliente, perfettamente adatto a commentare la società corrotta e affascinante della Repubblica di Weimar.

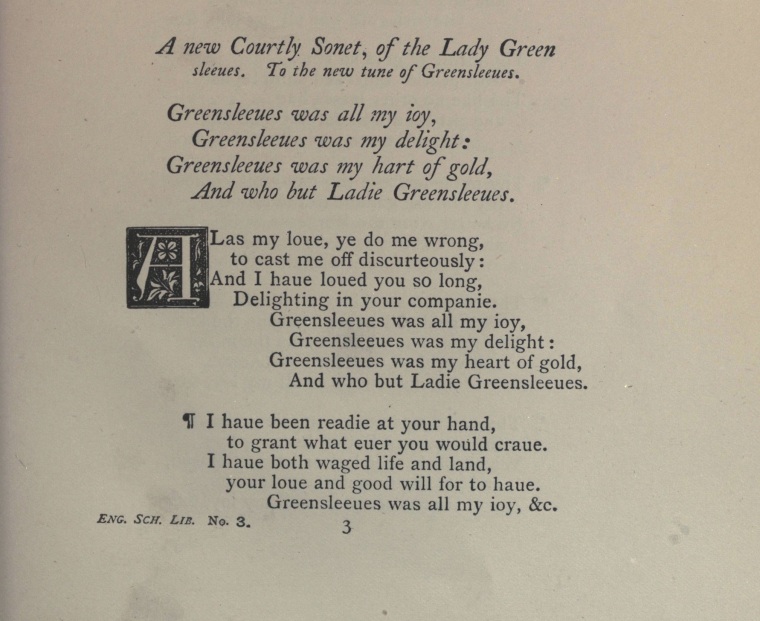

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

From a reprint, dated 1878, of A Handful of Pleasant Delites

English translation: please

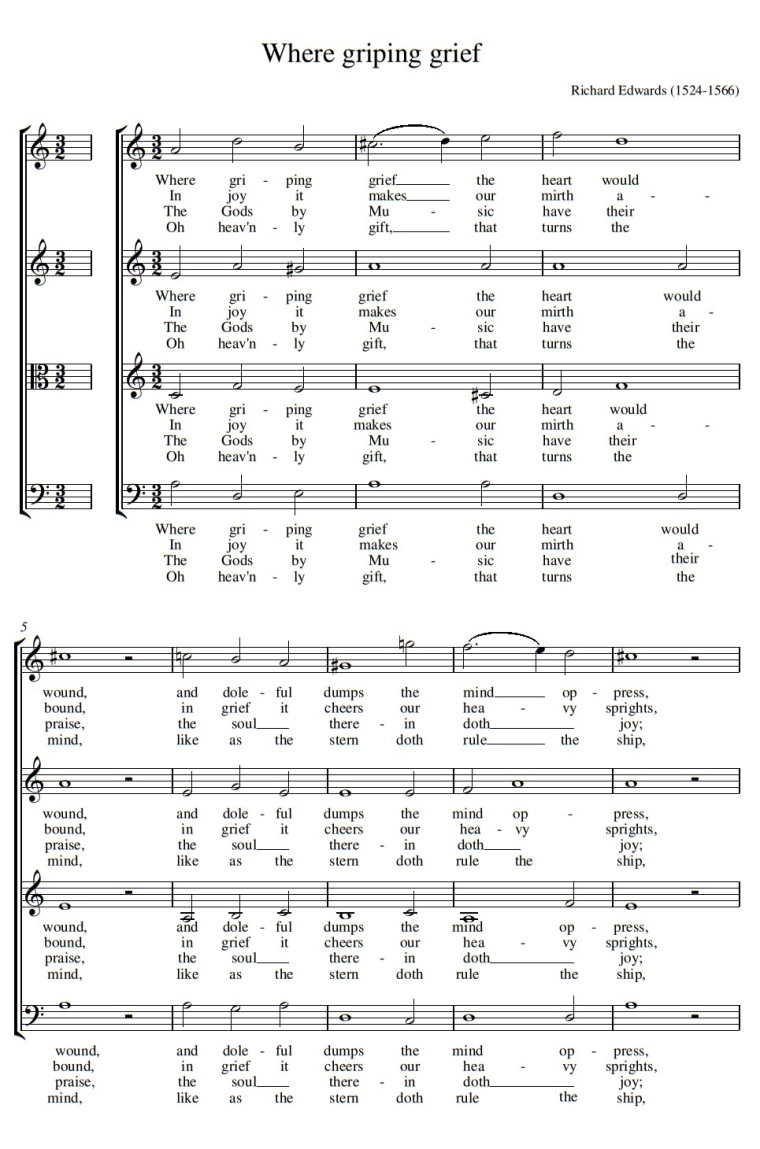

English translation: please  Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

Forse figlio illegittimo di Enrico VIII, Richard Edwardes fu poeta, autore drammatico, gentiluomo della Chapel Royal e maestro del coro di voci bianche della medesima istituzione sotto le regine Maria e Elisabetta I. Nei suoi ultimi anni compilò un’ampia silloge di testi poetici di autori diversi, cui aggiunse, firmandoli, alcuni componimenti propri, e fra questi appunto Where gripyng grief, con il titolo In commendation of Musick. La raccolta, intitolata The Paradise of Dainty Devices, fu pubblicata postuma nel 1576, a cura di Henry Disle; dei molti volumi miscellanei dati alle stampe in quel periodo fu il più fortunato, tant’è vero che fu ristampato nove volte nei successivi trent’anni.

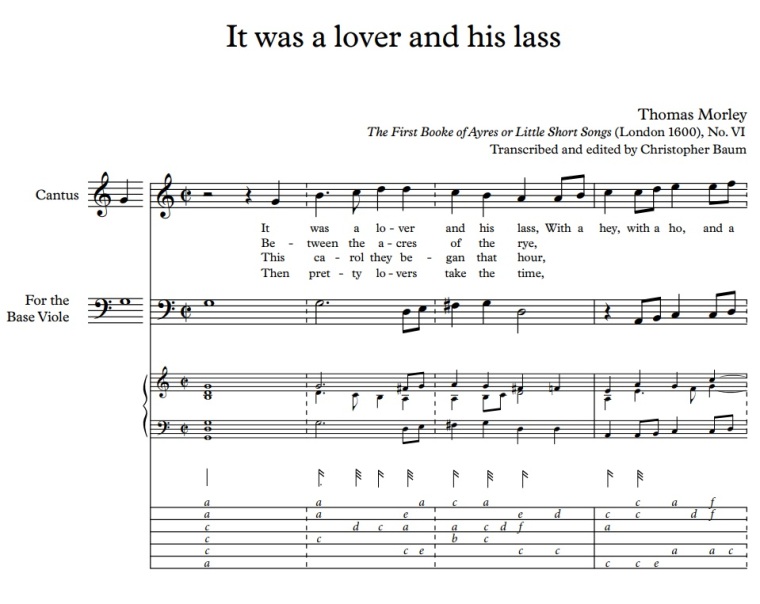

Nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728), scritta da John Gay, con musiche tratte perlopiù dal repertorio popolare e adattate da Johann Christoph Pepusch, trova posto anche la melodia di Greensleeves. Il brano è intonato con rabbia e frustrazione da Macheath subito dopo aver appreso di essere stato condannato a morte. Per «Tyburn Tree» si intende la forca: Tyburn era il villaggio del Middlesex in cui si eseguivano le sentenze capitali.

Nell’Opera del mendicante (The Beggar’s Opera, 1728), scritta da John Gay, con musiche tratte perlopiù dal repertorio popolare e adattate da Johann Christoph Pepusch, trova posto anche la melodia di Greensleeves. Il brano è intonato con rabbia e frustrazione da Macheath subito dopo aver appreso di essere stato condannato a morte. Per «Tyburn Tree» si intende la forca: Tyburn era il villaggio del Middlesex in cui si eseguivano le sentenze capitali.

Eugène Delacroix: Hamlet et Horatio au cimetière (1839), Paris, Louvre

Eugène Delacroix: Hamlet et Horatio au cimetière (1839), Paris, Louvre  Dopo aver ascoltato

Dopo aver ascoltato